Research - (2022) Volume 10, Issue 6

A Study of Psychosocial Aspects in Infertile Women

P Kartheeka, Kalarani and G Jayalakshmi*

*Correspondence: G Jayalakshmi, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Sri Lakshmi Narayana Institute of Medical Sciences Affiliated to Bharath Institute of Higher Education and Research, India, Email:

Abstract

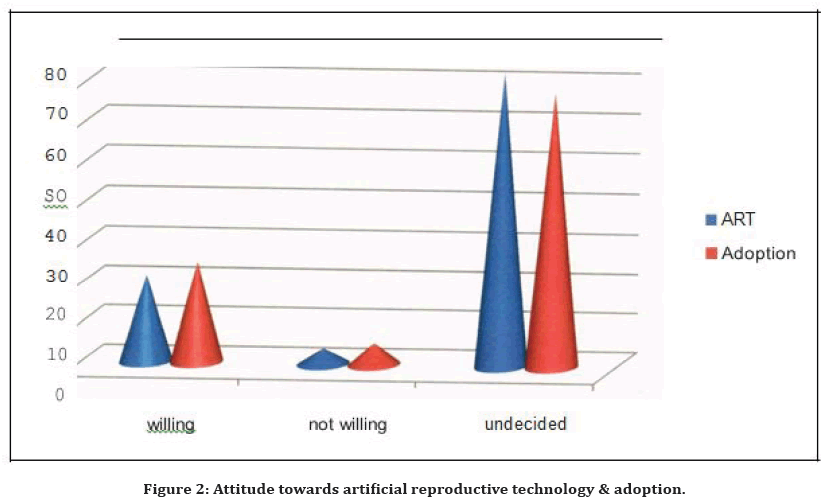

Most couples are taken aback when they discover they are infertile. For many people, having children is a matter of when, not if. When compared to infertile males, infertile women feel more psychological discomfort, worse self-esteem, and higher degrees of despair. The goal of this study was to determine the psychosocial variables that are linked to these abnormalities. Anxiety was more common among women from joint households than depression. Those who grew up in nuclear families were more depressed. Anxiety was more common among women with a favorable family background. Hypothyroidism and PCOS were linked to higher levels of anxiety and depression in females with hypothyroidism and PCOS, respectively. Women were more likely than males to be threatened with divorce or commit suicide. This woman suffered from anxiety as well as sadness. Anxiety was linked to a higher likelihood of divorce, whereas depression was linked to a higher risk of suicide. In researching how people feel about artificial reproductive technology (ART) and adoption. The majority chose adoption, owing to a desire to fulfill their maternal role. However, the majority of people were unclear about their opinions, preferences, and decisions.

Keywords

Impotency, Infertility, Hypothyroidism, Psychological values

Introduction

Over a year of frequent unprotected sexual intercourse, infertility is defined as the inability to conceive. It affects one out of every six child-bearing couples (17%). Over the previous 30 years, the rate of infertility has risen by 10%. This has been ascribed to a number of variables, including older age at marriage, postponed childbearing, the use of birth control, and an increase in the frequency of sexually transmitted diseases [1]. The most popular perception of infertility is that it is caused by a woman's inability to conceive. Medical studies have indicated that 40% of infertility is due to female causes, 40% is due to male factors, and the remaining 20% is due to an interaction between the two couples [2,3].

Approximately 75% of women who are diagnosed with infertility will seek therapy [4]. It is expected that 50 to 60% of individuals who seek therapy would conceive, compared to just 5% who would conceive if they did not seek medical help [5]. Infertility is one of those illnesses in medicine where, in addition to the medical features, emotional factors play a significant role [6]. In recent years, the influence of infertility on psychological wellbeing has received increased attention. Learning how to handle infertility in regard to oneself, one's spouse, and in other social domains is one of the most difficult tasks an infertile woman encounters.

Normal women in our culture are expected to produce children. Having a kid helps to keep the family together and improves marital satisfaction. Pretending to be pregnant is a frequent childhood hobby for little girls, but it would be an unusual individual who would dress up infertility as a future concern. Infertility affects both partners' self-esteem, sexual identity, and body image. In order to cope with the emotional and social effects of this type of handicap, the couple must find a new equilibrium. Negative attitudes around infertility are rampant in our culture and society. Having a kid appears to be a crucial component for women, and the absence of children may result in marital issues such as divorce or even a second marriage. The woman is usually the one who takes the brunt of the abuse. Infertility will put even the strongest marriages to the test, and couples may benefit from counselling or support organisations such as RESOLVE. Intervention of relatives, particularly the husband's family, as well as unfavourable attitudes and behaviour of the environment (family, friends, neighbors, etc.) contribute to women's psychological issues. Infertile women, in general, suffer from unfavourable societal effects such as marital instability, stigmatization, and maltreatment.

Infertility is a traumatic, unexpected, and life-altering experience. When a couple is told they are infertile, they typically become angry. Most couples' rage is a reaction to their feelings of helplessness and impotence when they lose control over their life choices [7]. Infertility diagnosis and treatment have a significant impact on people's lives and thoughts. Patients who are infertile require particular psychological care, not only to cope with the pain of not being able to have a child, but also to cope with the tests and therapies that can have a negative psychological impact examinations and treatment can disturb the intimacy and balance of the couple [8]. Women are compelled to be more active in therapeutic processes, and this is the sole reason they are more impacted. The goal of this study was to see how common anxiety and despair were among infertile women.

Materials and Methods

During the months of August 2010 and August 2012, 200 women were enrolled in this research at Sree Balaji Medical College And Hospital's "Infertility Clinic." Women between the ages of 20 and 45 who had reproductive concerns and were willing to participate were included in the study. The research excluded women aged 20 to 45, as well as those with secondary infertility and a history of pregnancy loss. Demographic information, gynecological history, and marital and sexual history were all documented. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (RADS) was used to conduct the psychological evaluation. The obtained results have been rigorously examined and presented.

Results

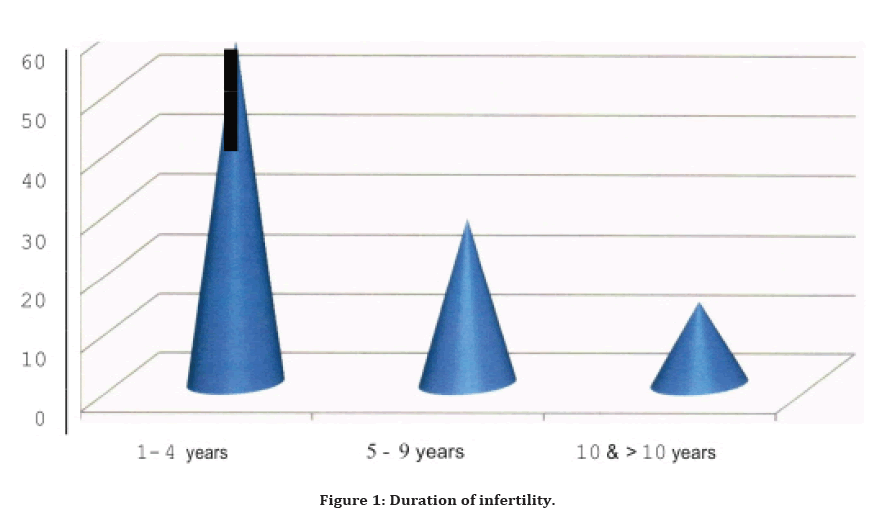

Results are described in Tables (Tables 1-9) and Figures (Figures 1 and 2).

| Minimum age (years) | Maximum age (years) |

|---|---|

| 20 | 45 |

| Range is 20 to 45 years | |

Table 1: Age of patients.

| Duration (in years) | Women |

|---|---|

| 1-4 | 116 (58%) |

| 5-9 | 56 (28%) |

| 10 & >10 | 28 (14%) |

| Total | 200(100%) |

Table 2: Duration of infertility.

| Class | Women |

|---|---|

| Upper middle (class 2) | 6(3%) |

| Lower middle (class 3) | 16(8%) |

| Upper lower (class 4) | 178(89%) |

| Total | 200 (100%) |

Table 3: Socio economic class.

| Threat to divorce | Suicidal attempts | |

|---|---|---|

| Present | 11(5 ) | 10(5%) |

| Absent | 189(94%) | 190(95%) |

| Total | 200(100%) | 200(100%) |

Table 4: Threat to divorce and suicidal attempts.

| Age group in years | 20-29 | 30-39 | 40 & >40 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety & depression absent | 47(32.4%) | 9(18.7%) | 1(14.3%) |

| Anxiety present | 56(38.6%) | 20(41.6%) | 4 (57.1%) |

| Depression present | 37(25.5%) | 17(35.4%) | 2 (28.5%) |

| Both present | 5(3.4%) | 2(4.1%) | - |

| Total | 145 | 48 | 7 |

Table 5: Age group distribution and prevalence of anxiety and depression.

| Marital problem | Anxiety and depression absent | Anxiety | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Present | 5(50%) | 5(50%) | 10 |

| Absent | 108(56.8%) | 82(43.1%) | 190 |

| Total | 113(56.5%) | 87(43.5%) | 200 |

Table 6: Marital problems in anxiety and depression.

| Past history | Anxiety and depression absent | Anxiety | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Present | - | - | - |

| Absent | 113(56.5%) | 87(43.5%) | 200 |

| Total | 113(56.5%) | 87(43.5%) | 200 |

Table 7: Relationship of past psychological disturbance to anxiety and depression.

| Hypothyroidism | Anxiety and depression absent | Anxiety | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Present | 10(50%) | 10(50%) | 20 |

| Absent | 103(57.2%) | 77(42.7%) | 180 |

| Total | 113(56.5%) | 87(43.5%) | 200 |

Table 8: Hypothyroidism in anxiety and depression.

| Willing | Not willing | Undecided | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artificial reproductive technology | 44(22%) | 8(4%) | 148(74%) | 200(100%) |

| Adoption | 51(25.5%) | 11(5.5%) | 138(69%) | 200(100%) |

Table 9: Attitude towards artificial reproductive technology& adoption.

Figure 1. Duration of infertility.

Figure 2. Attitude towards artificial reproductive technology & adoption.

Discussion

Women appeared to be more stressed than men as a result of the infertility problem, indicating an allocation of responsibilities in the couples such that women suffered more of the emotional load associated with an unmet wish for a child and sought medical diagnosis and treatment earlier than men. The most striking difference was the study group's increased level of anxiety, sadness, and somatization when compared to the control group. At the same time, both couples had a propensity to have a much more optimistic attitude toward areas of life outside of the reproductive problem than the reference group, which may most likely be understood as a useful coping strategy for dealing with the fertility crisis. The study's most notable feature was its assessment of the depression rate among infertile women. The stress of infertility is felt by women who are dealing with infertility issues. Depression inventory, 28.3 percent of infertile women had mild - to - moderate depression, 7.2 percent had mild to high depression, and 1.2 percent had the most severe depression [1-8].

Conclusion

Psychological disturbances were present in 80 women (40%) had anxiety alone, 56 women (23%) had depression alone and 7 women (3.5%) had both. It was seen in our study that 62 women (31%) had mild anxiety, 23 women (11.5%) had moderate anxiety and 2 women (1%) had severe anxiety. Diagnosing and treating hypothyroidism will help m improving both the wellbeing of the patient as well the fertility outcome.

References

- McDaniel SH, Hepworth J, Doherty W. Medical family therapy with couples facing infertility. Am J Family Therapy 1992; 20:101-122.

- Robinson GE, Stewart DE. The psychological impact of infertility and new reproductive technologies. Harvard Rev Psychiatr 1996; 4:168-172.

- Brkovich AM, Fisher WA. Psychological distress and infertility: Forty years of research. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol 1998; 19:218-228.

- Wilson JF, Kopitzke EJ. Stress and infertility. Curr Womens Health Report 2002; 2:194-202.

- Andrews FM, Abbey A, Halman LJ. Stress from infertility, marriage factors, and subjective well-being of wives and husbands. J Health Social Behav 1991; 238-253.

- Adashi EY, Cohen J, Hamberger L, et al. Public perception on infertility and its treatment: An international survey. Bertarelli foundation scientific board. Human Reprod 2000; 15:330-334.

- Shapiro CH. The impact of infertility on the marital relationship. Social Casework 1982; 63:387-393.

- Oddens BJ, den Tonkelaar I, Nieuwenhuyse H. Psychosocial experiences in women facing fertility problems: A comparative survey. Hum Reprod 1999; 14:255-261.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Author Info

P Kartheeka, Kalarani and G Jayalakshmi*

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Sri Lakshmi Narayana Institute of Medical Sciences Affiliated to Bharath Institute of Higher Education and Research, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, IndiaReceived: 16-May-2022, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-66695; , Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-66695 (PQ); Editor assigned: 18-May-2022, Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-66695 (PQ); Reviewed: 02-Jun-2022, QC No. JRMDS-22-66695; Revised: 07-Jun-2022, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-66695 (R); Published: 14-Jun-2022