Research - (2021) Volume 9, Issue 6

A Study on Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Findings in Patients Admitted with Upper GI Bleed

Sunil T George, A Sankar and G Jagan*

*Correspondence: G Jagan, Department of General Medicine, Sree Balaji Medical College & Hospital Affiliated to Bharath Institute of Higher Education and Research, India, Email:

Abstract

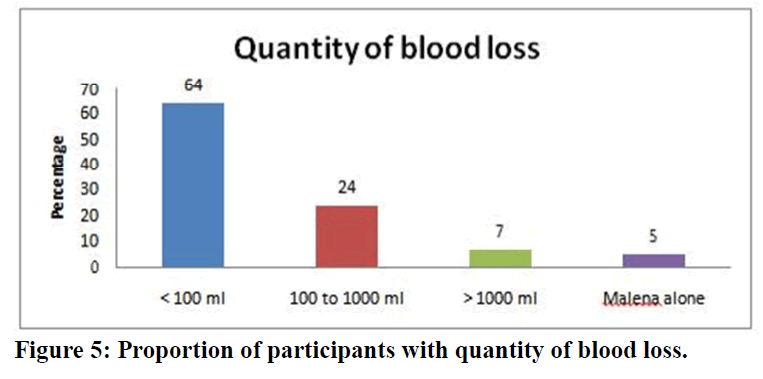

To find out the prevalence of nature of lesion on Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy in patients admitted for UGI bleed. To find out the prevalence of nature of lesion in patients with minor, moderate, major bleed. general prevalence of acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage has been assessed to be 50-100 in line with 1,00,000 people according to year, with an annual hospitalization rate of approximately a 100 in keeping with 1, 00,000 health facility admission. The peptic ulcer disease was the most common lesion found on endoscopy with prevalence of 52%.Varices contributes second common lesion, next to peptic ulcer disease in UGI bleed with prevalence of 13%. Minor UGI bleed was the commonest presentation. Majority of lesions (64%) presented with minor UGI bleed 24% lesions presented as moderate UGI bleed.

Keywords

Hemorrhage, Endoscopy, Lesion, Hematemesis, Bleeding

Introduction

The spectrum of gastrointestinal bleeding may involve many distinctive situations. The reason for this variety is that bleeding can arise from multiple different lesions and numerous sites inside the gastrointestinal tract. Gastrointestinal bleeding is a not an unusual clinical problem needing more than 200,000 hospitalization yearly. Upper Gastrointestinal bleeding, which most regularly arises from mucosal erosive diseases, account for up to 20,000 deaths yearly [1-3].

The general prevalence of acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage has been assessed to be 50-100 in line with 1,00,000 people according to year, with an annual hospitalization rate of approximately a 100 in keeping with 1, 00,000 health facility admission. Bleeding from upper GI tract is about 5 times commoner than bleeding from lower gastrointestinal tract. Bleeding can be major or minor, apparent or obscure. Gastrointestinal bleeding presents clinically in one of the four ways. Hematemesis (from the upper GIT). Hematochezia (from the lower GIT) ccult (unknown to the patient) Obscure (from an unknown site in the GIT) [4,5].

The most vital elements in managing gastrointestinal bleeding based on the following Source of bleed, Stop active bleed, Treat underlying abnormality and Prevent recurrent bleed. Historically, the causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding have been gastroduodenal ulcers, although other upper gastrointestinal tract mucosal lesions account for a significant share of cases [6].

Materials and Methods

Place of study : Department of General Medicine, Sree Balaji Medical College & Hospital, Chrompet, Chennai

Type of study: Prospective study

Period of study: April 2018- July 2019

Ethical Committee approval: The present study was approved by the Ethical Committee

Collaborating Department: Department of Medical Gastroenterology.

Consent: Written informed consent was obtained from patients in English and the native language.

Selection of patients

Hundred patients fulfilling the following inclusion criteria and not having any of the exclusion criteria were taken up for the study.

Inclusion criteria

All adult patients of both sexes who were giving definite history of vomiting of frank blood or coffee ground coloured vomit and/ or passed dark coloured stools were chosen for this study. Inpatients admitted for other illnesses and who subsequently developed UGI bleeding following prescription with drugs like aspirin, other NSAIDS, steroids, anticoagulants and other gastro toxic drugs were also included Inpatients who developed UGI bleed after administration for severe medical illness like respiratory failure, sepsis.

Exclusion criteria

The following groups of patients were excluded from this study after detailed history taking, clinical examination and investigations because of the confounding factors which will interfere with the results.

Patient characteristics like age and sex were recorded. Precise records regarding the UGI bleeding like number of episodes of hematemesis approximate quantity of blood vomited each time, association with Malena or presenting with Malena alone were obtained. Symptoms of common diseases that could result in UGI bleeding and unique records of drug consumption like aspirin, different NSAIDs, steroids and symptoms of blood loss had been recorded in the questionnaire. Endoscopy performed for all of the patients after overnight fasting, using Olympus video endoscopic system, to at once visualize the mucosa of the oesophagus, stomach and duodenum, like varices, ulcers, erosions. The endoscopic stigma of active or recent hemorrhage and endoscopic prognostic features like number of ulcers, location of ulcers, size of ulcers, bleeding or not healing or not, clean base of the ulcer or adherent blood clot, oozing of blood from the ulcer base and those seen blood vessel had been studied. The location, grading of varices were studied and evaluation for rare causes for UGI bleed had been made.

Study approach

Number of patients affected, were studied in relation to age group, estimated amount of total blood loss, incidence of endoscopic findings in UGI bleed.

Results

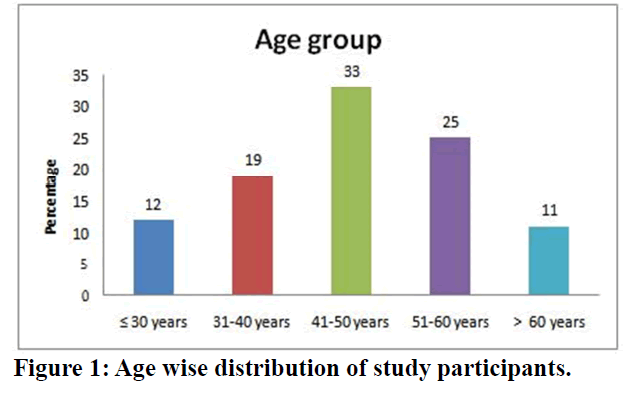

In this study among 100 participants 12% of them were below 30 years of age, followed by 19% of the participants between 31 -40 years, 33% of the study participants were in the age range of 41 -50 years. Between the age of 51-60 years there were 25% of the participants in this study and 11% of the participants were above 60 years of age (Figure 1). In this study 76% of the participants were males while 24% of the participants were females (Table 1).

| Gender | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Male | 76 |

| Female | 24 |

| Total | 100 |

Table 1: Proportion of participants based on gender.

Figure 1. Age wise distribution of study participants.

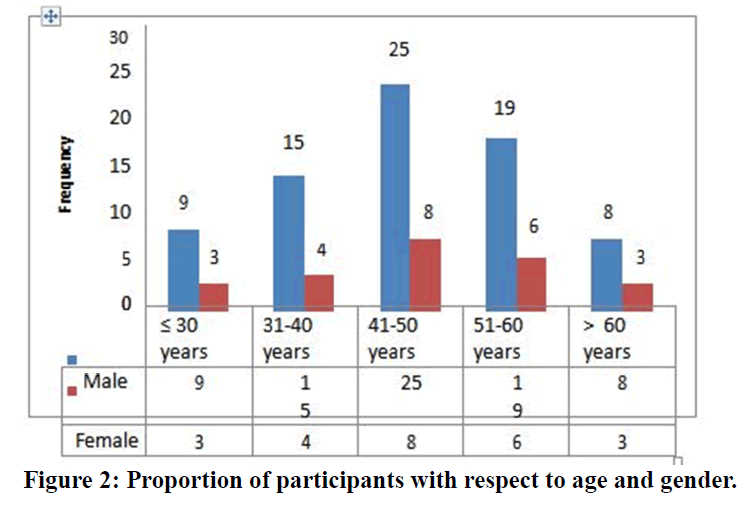

Among 12% of the participants below 30 years of age 9 was males, whereas among 19% of the participants in the age group of 31-40 years 15 participants were found to be males. There were 25%, 19% and 8% of males in the age group of 41-50 years, 51-60 years and above 60 years respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Proportion of participants with respect to age and gender.

In this study among the hundred participants 53% of the participants gave positive history that they were known cases of peptic ulcer disease (Table 2).

| Known case of PUD | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Yes | 53 |

| No | 47 |

| Total | 100 |

Table 2: Proportion of participants with peptic ulcer disease.

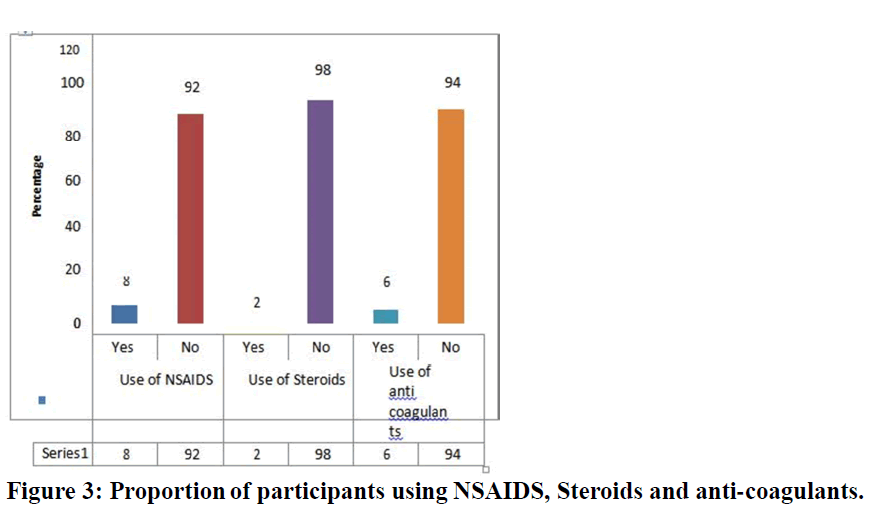

Among 100 participants 32% of the participants were found to be alcohol consumers and smoking habit was seen in 41% of the study participants, whereas 59% of the participants were non-smokers (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Proportion of participants using NSAIDS, Steroids and anti-coagulants.

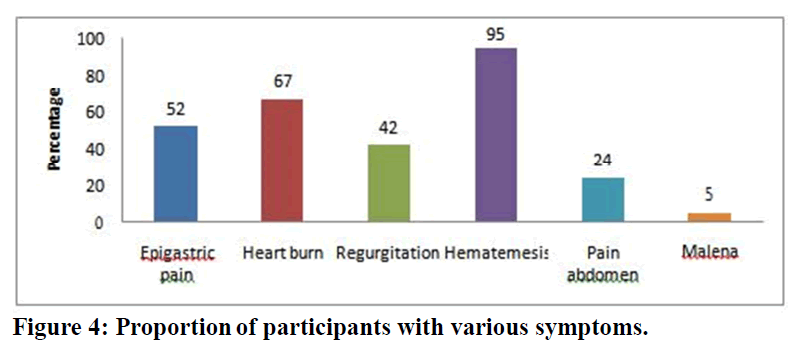

Similar illness like gastritis was present in 7% of the study participants whereas 93% of the participants do not have similar past history (Table 3). The common symptoms among the study participants was found to be hematemesis in 95% of the participants, heart burn in 67% of the participants, Epigastric pain among 52% of the participants, regurgitation in 42% of the participants. Pain abdomen was the symptom in 24% of the study participants whereas Malena was seen in 5% of the study participants (Figure 4).

| Past history of similar illness | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Yes | 7 |

| No | 93 |

| Total | 100 |

Table 3: Proportion of participants with similar past history.

Figure 4. Proportion of participants with various symptoms.

In this study the amount of blood loss was less than 100 ml in 64% of the participants while it was 100 to 1000 ml in 24% of the participants. The amount of blood loss was more than 1000ml in 7% of the participants. Malena alone was noted in 5% of the study participants (Figure 5). Among 95 participants with hematemesis, 46 participants had single episode of hematemesis whereas 26 participants had two episodes. The frequency of hematemesis was three, four and five among 14, 7 and 2 participants respectively (Table 4).

| Number of episodes of Hematemesis | Frequency |

|---|---|

| One | 46 |

| Two | 26 |

| Three | 14 |

| Four | 7 |

| Five | 2 |

| Total | 95 |

Table 4: Frequency of Hematemesis among study participants.

Figure 5. Proportion of participants with quantity of blood loss.

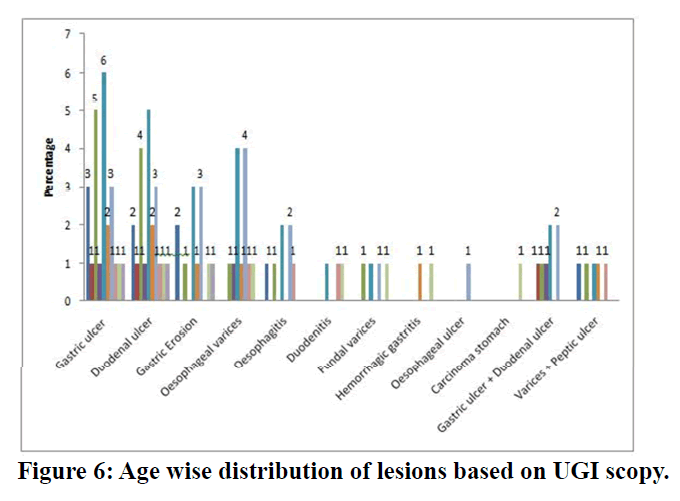

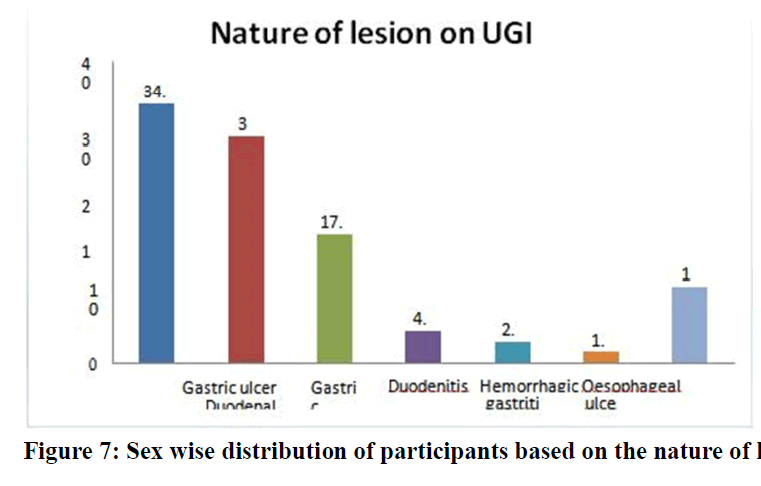

Among 24 participants with gastric ulcer 18 were males and 6 were females. In 21 participants with duodenal ulcer 15 were males and 6 were females. whereas among 12 gastric erosion cases 10 were males and 2 were females. Duodenitis was seen among 3 participants of whom 2 were males and 1 was female. The sex distribution of hemorrhagic gastritis was 1:1. Esophageal ulcer was noted in 1 male participant. Among 7 Oesophagitis cases 6 were males and one was female (Table 5) (Figure 6 and Figure 7).

| Nature of lesion on UGI scopy | Male | Female | Total | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gastric ulcer alone | 18 | 6 | 24 | 34.3 |

| Duodenal ulcer alone | 15 | 6 | 21 | 30 |

| Gastric Erosion | 10 | 2 | 12 | 17.1 |

| Duodenitis | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4.3 |

| Hemorrhagic gastritis | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2.9 |

| Oesophageal ulcer | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1.4 |

| Oesophagitis | 6 | 1 | 7 | 10 |

| Total | 53 | 17 | 70 | 100 |

Table 5: Sex wise distribution of participants based on the nature of lesion on UGI scopy.

Figure 6. Age wise distribution of lesions based on UGI scopy.

Figure 7. Sex wise distribution of participants based on the nature of lesion on UGI scopy.

Discussion

Out of one hundred patients studied, seventy-six were male patients and twenty-four were females. In a Scandinavian study, it was found that incidence of UGI bleeding was twice as high among men as among women. The percentage of number of patients in the age group of 41 years of age and above was 58% comprising more than ½ of all the patients. In this study it was found that older patients bleed in a high incidence because the frequency of bleeding is directly related to the duration of the disease. The increased incidence of UGI bleed in elderly individuals were also due to frequent prescription of NSAIDs and aspirin for their cardiac problems and the relative risk was 2.0 times higher than the others [7,8]. In the relative risk for elderly patients was 3.8 times than the others. Percentage of patients with one or two episodes of hematemesis was 72%. 64% of the patients admitted for UGI bleed were having minor UGI bleed (<100 ml). Only 7% of the patients had severe UGI bleeding (more than 1000ml) in the present study and majority of the patients 45% were found to have gastric and duodenal ulcer on endoscopy [9].

In this study among 7 cases of major UGI bleed, Esophageal varices (4 cases) and gastric+duodenal ulcer (2 case) contributes 50% of total number of major UGI bleed. Rupture of varices is the most common cause of life- threatening hemorrhage. Risk of bleeding is greatest when varices are large and when they are prominent in the gastric fundus [10]. In the present study, patients had undergone delayed UGI endoscopy by three to five days. The prevalence of nature of lesions is as follows. In this study, gastric ulcer alone 24 cases (24%), duodenal ulcers alone 21 cases (21%) and both lesions in a same patient 7% collectively remain the most common cause of UGI bleed with total of 52%. In American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Chronic gastric and duodenal ulcers collectively remain the most common cause of hematemesis and melena. Reported peptic ulcer was the most common lesion on endoscopy in cases with UGI bleed. The increased frequency of gastric ulcers bleed than duodenal ulcers is likely to be due to gastric ulcers have a slightly greater tendency to bleed than duodenal ulcers, 23.7 % compared with 19.1% [11].

In this study, both esophageal and fundal varices contributes 17% of cases of total UGI bleed. Compiled esophageal varices accounted for an overall 7.3% to 11.1% in his study. In OMGE International upper GI Bleeding survey, 1978-86, Esophageal varices was the second most common cause of UGI bleed. A quoted 7-20% cases of UGI bleed were due to varices. In this study, 12% of cases were due to gastric erosion. Above the resultsmentioned 2-7 % of UGI bleed were due to gastric erosion. Erosive gastritis 7-22% were reported [12-15]. Epidemiology and course of GIH, British The American Society for gastrointestinal Endoscopy National Survey of UGI bleed (Gilbert DA, Tedesco FJ, et al), reported 23.4% cases of gastric erosions. Alum et al described 4.1 cases of gastric carcinoma as a cause of acute GIT bleed, 2-7% cases of gastric carcinoma [16,17].

In this study, 5% UGI bleed had both varices and peptic ulcer findings on Endoscopy. In this study, varices and peptic ulcer (4 cases) contributes 20% of total number of varices cases.; mentioned other sources of bleeding in esophageal varices patients include gastric and duodenal ulcers in up to 20% of cases [18-21]. In our study, 3 cases of UGI bleed were found to have Duodenitis on Endoscopy. As observed, friable and punctuate erosions of a slight nodular mucosa, predominantly in the duodenal bulb, can be a source of bleeding. I In ASGE39 Survey duodenitis was observed in 5.8% cases. Other causes of UGI bleed that occurs in less frequency in this study includes one case of Esophageal ulcer, 2 Hemorrhagic gastritis [22-26].

Conclusion

The study on endoscopic findings in upper gastrointestinal bleed concludes that the peptic ulcer disease was the most common lesion found on endoscopy with prevalence of 52%.Varices contributes second common lesion, next to peptic ulcer disease in UGI bleed with prevalence of 13%. Minor UGI bleed was the commonest presentation. Majority of lesions (64%) presented with minor UGI bleed 24% lesions presented as moderate UGI bleed. Only 7% presented as major UGI bleed. Varices account for the most common cause for major UGI bleed contributing 57%. Gastric ulcer was commonest lesions accounting for 24 cases (34.3%) among cases having single acid peptic lesions on endoscopy. The second most common is duodenal ulcer (30%). Multiple lesions were found in 12% of cases. Peptic ulcer lesions were found in 22% of total number of varices cases.

Funding

No funding sources.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledegements

The encouragement and support from Bharath University, Chennai, is gratefully acknowledged. For provided the laboratory facilities to carry out the research work.

References

- https://issuu.com/sibdi/docs/gastrointestinal_and_liver_disease

- Long Streth GF. Epidemiology of hospitalization for acute upper gastro intestinal haemorrhage: A population based study. AMJ Gastro Entero 1995; l 90:206.

- Van Lee rdan ME, Ureeburg EM, Rauws, EA, et al. Acute upper GI bleeding: Did anything change? Time trend analysis of incidence and outcome of acute upper gastro intestinal bleeding between 1993/1994 and 2000. AMJ Gastro Enterol 2007; 98:1494.

- Bharucha AE, GostoutCJ, BalmRK. Clinical and endoscopic risk factors in the mallory weiss syndrome. AMJ Gastro Enterol 1997; 92:805.

- Kaufman DW, Kelly JP, Wiholm BE, et al. The risk of acute major upper gastro intestinal bleeding among users of aspirin and ibuprofen at various levels of alcohol consumption. AMJ Gastro Enterol 1999; 94:3189.

- Beppu K, Inoquachik, Koyanagi N, et al. Prediction of variceal hemorrhage by esophageal endoscopy: Gastrointest Endosc 1981; 27:213.

- Laine L, Weinstein WM. Subepithelial hemorrhages and erosions of human stomach. Digestive Dis Sci 1988; 33:490-503.

- Sivakumar K. A Study on Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopic findings in patient admitted with UGI bleed (Doctoral dissertation, Thanjavur Medical College, Thanjavur).

- Foutch PG. Angiodysplasia of the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Gastroenterol 1993; 88.

- Longacre AV, Gross CP, Gallitelli M, et al. Diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal bleeding in patients with hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia. Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98:59-65.

- Rodríguez-Pérez F, Groszmann RJ. Pharmacologic treatment of portal hypertension. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 1992; 21:15-40.

- Myers JD. An estimation of portal venous pressure by occlusive catheterization of an hepatic venule. J Clin Invest 1951; 30:662.

- Nevens F, Bustami R, Scheys I, et al. Variceal pressure is a factor predicting the risk of a first variceal bleeding: A prospective cohort study in cirrhotic patients. Hepatology 1998; 27:15-9.

- Abraldes JG, Bosch J. Somatostatin and analogues in portal hypertension. Hepatology 2002; 35:1305-12.

- D’Amico G, Pietrosi G, Tarantino I, et al. Emergency sclerotherapy versus vasoactive drugs for variceal bleeding in cirrhosis: A cochrane meta-analysis. Gastroenterol 2003; 124:1277-91.

- Ben-Ari Z, Cardin F, McCormick AP, et al. A predictive model for failure to control bleeding during acute variceal haemorrhage. J Hepatol 1999; 31:443-50.

- Zimmerman J, Siguencia J, Tsvnag E, et al. Predictors of mortality in hospitalized patients with secondary upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Scand J Gastronterol 1995; 30:327-31.

- Sarin SK, Lahoti D, Saxena SP, et al. Prevalence, classification and natural history of gastric varices: A long‐term follow‐up study in 568 portal hypertension patients. Hepatology 1992; 16:1343-9.

- Kim T, Shijo H, Kokawa H, et al. Risk factors for hemorrhage from gastric fundal varices. Hepatology 1997; 25:307-12.

- Rockall TA, Logan RFA, Devlin HB, et al. Risk assessment after acute upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage. Gut 1996; 38:316-21.

- Jensen DM, Machicado GA, Kovacs TOG, et al. Controlled, randomized study of heater probe and BICAP for hemostasis of severe ulcer bleeding. Gastroenterology 1988; 94:A208.

- Forrest JA, Finalyson ND, Sherarman DJ. Endoscopy in gastrointestinal bleeding. Lancet 1974; 2:394–97.

- Morgan AG, McAdam WAF, Walmsley GL, et al. Clinical findings, early endoscopy, and multivariate analysis in patients from the upper gastrointestinal tract. BMJ 1977; 2:237–40.

- Shiller KFR, Truelove SC, William DG. Haematemesis and melena, with special reference to factors influencing the outcome. BMJ 1970; 2:7-14.

- Nishiaki M, Tada M, Yanai H, et al. Endoscopic hemostasis for bleeding peptic ulcer using hemostatic clip or pure ethanol injection. Hepatogastoenterology 2000; 47:1042–44.

- Savides TJ, Jensen DM, Cohen J, et al. Severs upper gastrointestinal tumour bleeding. Endoscopic findings, treatment and outcome. Endoscopy 1996; 28:244–48.

Author Info

Sunil T George, A Sankar and G Jagan*

Department of General Medicine, Sree Balaji Medical College & Hospital Affiliated to Bharath Institute of Higher Education and Research, IndiaCitation: Sunil T George, A Sankar, G Jagan,A Study on Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Findings in Patients Admitted with Upper GI Bleed, J Res Med Dent Sci, 2021, 9(6): 306-311

Received: 01-Apr-2021 Accepted: 23-Jun-2021