Research - (2022) Volume 10, Issue 6

Association of Age and Gender Distribution of Class III Cavities Restored with Composite Restoration

Haripriya R and Surendar Sugumaran*

*Correspondence: Surendar Sugumaran, Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences (SIMATS), Saveetha University, India, Email:

Abstract

Introduction: G V Black classified dental caries based on the site of occurrence in which class III caries involve the anterior teeth and its restoration has a significant influence on esthetics. Composite resin is one of the most commonly used restorative material during the past decade as it provides desirable esthetics, easy to manipulate and minimal cavity preparation required. Aim: Aim of the present study is to analyse the association of age and gender distribution of class III cavities restored with composite restoration. Materials and methods: The study was done in a University setting. The data was collected by analyzing the radiographs from the patient software system of Saveetha Dental College and the samples included patients who underwent composite restoration in class III cavities. The data collected was tabulated and statistically analysed using the SPSS software version 21.0. The results were represented in the form of graphs. The level of significance was set at 0.05. Results: From the present study, we can conclude that the majority of the patients who have undergone class 3 restoration were between the age group of 31-40 years. In gender analysis, the majority of the patients were females. When the association between the age and gender of the patients who underwent class III restoration with respect to the number of turns was analysed, there was a significant difference in age (p-value was less than 0.01; p-value <0.05, significant.) In gender analysis, there was no significant association (p-value=0.186).

Keywords

Class III, Composite restoration, Aesthetics, Innovative technique, Dental caries

Introduction

Dental caries is one of the most important chronic diseases of the oral cavity which is prevalent worldwide. Dental caries is defined as an infectious microbiological disease of the teeth that results in localised dissolution and destruction of the calcified tissues [1]. It is a bacterial driven disease, which is chronic in nature, the multifactorial, site-specific, dynamic disease process that results due to imbalance in physiologic equilibrium between the tooth mineral content and the plaque fluid, i.e. When the pH drop results in net mineral loss overtime [2,3]. Dr. G V Black classified dental caries over a 100 years back based on the occurrence of the site of the caries [4]. Among these, Class 3 caries is associated with the anterior teeth. It involves the proximal surfaces (mesial and distal surfaces) of the anterior teeth [5]. Malocclusion; usually crowding and tight proximal contacts has an influence on this type of caries [6,7]. Caries usually start with white lesions which further progresses to dentin causing hypersensitivity which may lead to class III or class IV caries. Treatment options usually include composite restoration and veneering. If untreated, the caries progresses to the pulp causing pain and in long standing cases, the pulp becomes non- vital. In such cases, the root canal treatment is the choice of treatment [8].

Composite restoration is a tooth coloured restorative material which is commonly used to restore mild to moderately decayed teeth and has the benefit of improved esthetics as compared to other restorative materials in the market [9]. Composite restoration not only provides desirable esthetics but is also easy to manipulate and requires minimally invasive preparation technique and has replaced amalgams which have been the standard restorative material for the past 100 years as amalgam restorations have been associated with environmental pollution [10,11].

Our team has extensive knowledge and research experience that has translated into high quality publications [12–31]. The aim of the present study is to analyse the association of age and gender distribution of class III cavities restored with composite restoration.

Materials and Methods

The present study was a retrospective study that was conducted in a university setting. The ethical clearance for the study was obtained from the Institutional Scientific Review Board. The treatment records of patients who had undergone treatment in Saveetha Dental college between June 2019 to July 2021 were assessed for this study. The data collection and analysis was done by a single examiner. The inclusion criteria were patients in whom class 3 cavities were restored with composite restoration. The age and gender of the patients were recorded. Exclusion criteria for the study were incomplete case records and improper record on the number of layers of restoration. To avoid sampling bias, simple random sampling was done. The extracted data was tabulated in a spreadsheet (Excel 2017: Microsoft Office) and analysed using SPSS 21.0 version software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago). Descriptive statistics and chi-square tests were performed with the level of significance at 5% (P<0.05). The results were represented in the form of graphs.

Results

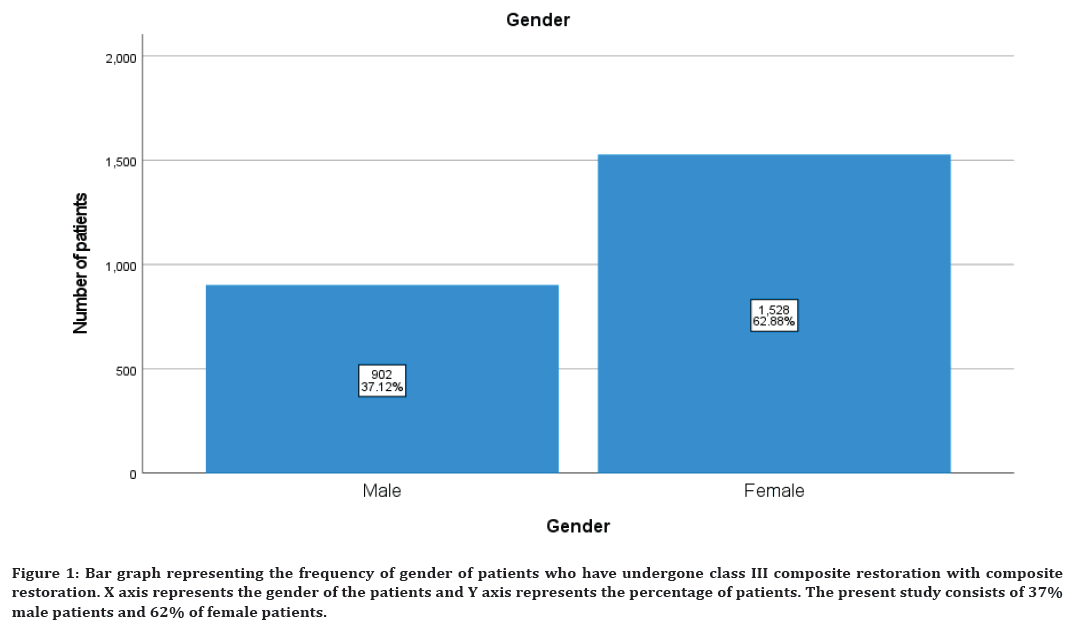

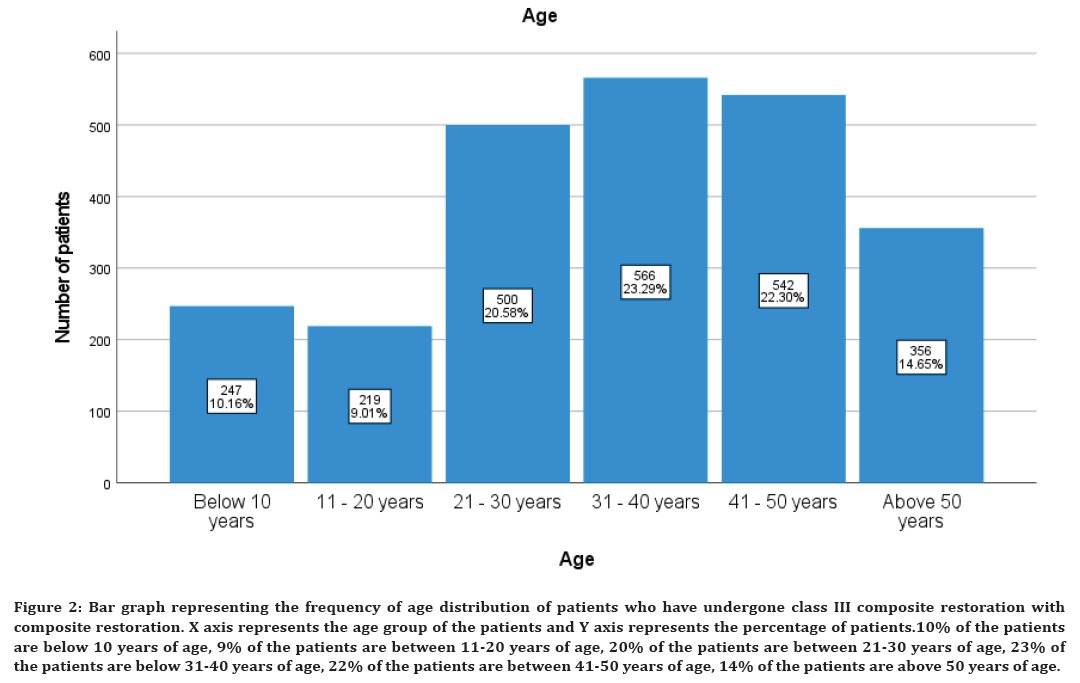

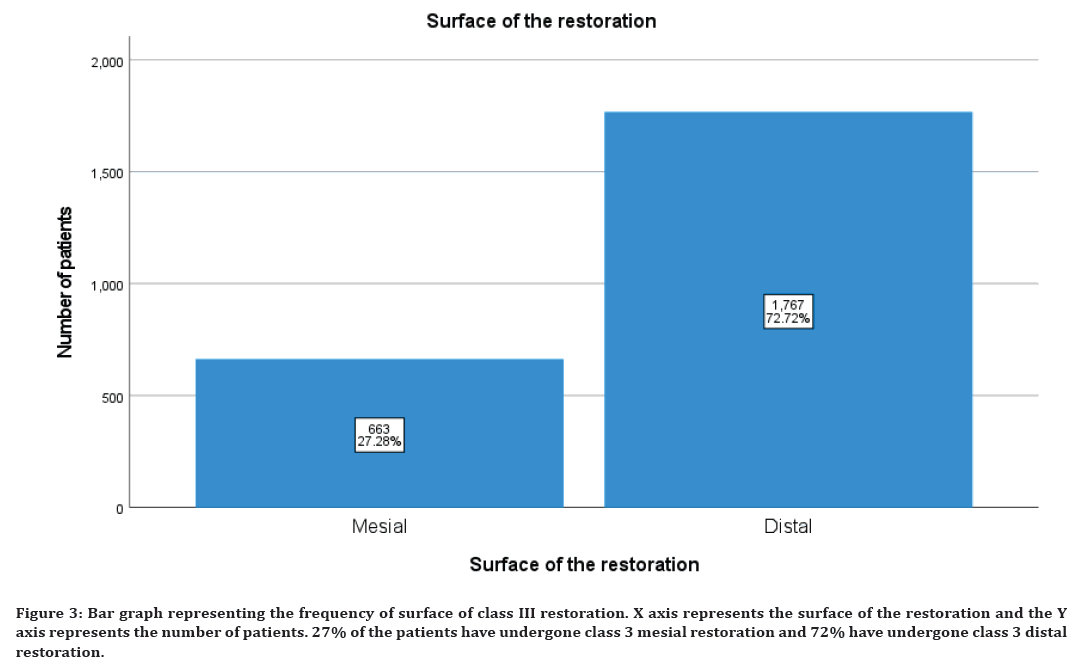

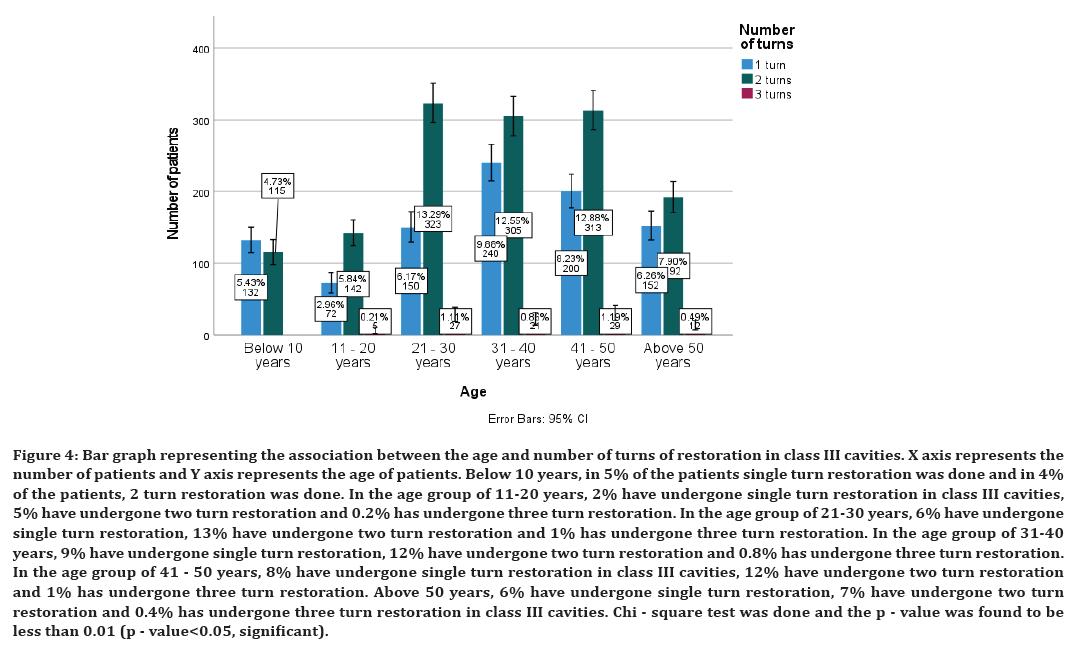

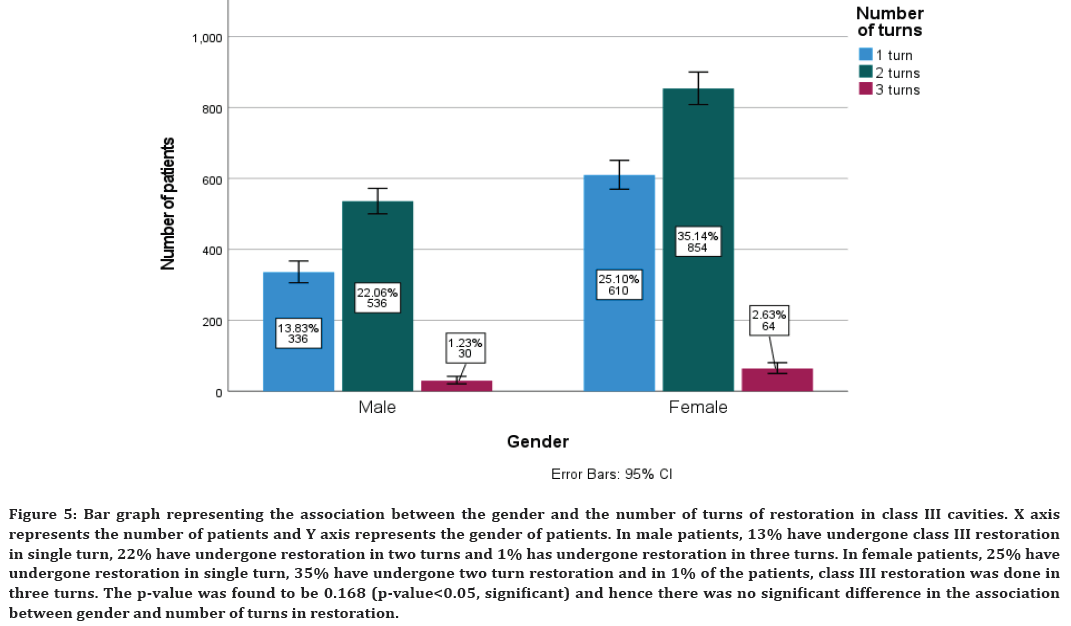

A total of 2430 patients were included in the present study which conveys that 2430 patients have undergone composite restoration in class 3 cavities. Among which, 37% were male and 62% were female (Figure 1). Majority of the patients who have undergone class 3 composite restoration were females. When the age distribution was analysed, 10% of the patients were below 10 years of age, 9% of the patients were between 11 - 20 years of age, 20% of the patients were between 21 - 30 years of age, 23% of the patients were below 31 - 40 years of age, 22% of the patients were between 41 - 50 years of age, 14% of the patients were above 50 years of age (Figure 2). Majority of the patients who have undergone class 3 composite restoration were between the age group of 31 - 40 years. Another analysis on the surface in which the restoration was done was taken into consideration. 27% of the patients have undergone class 3 mesial restoration and 72% have undergone restoration in the distal surface (Figure 3). When the association between age and the number of turns in class III restorations was analysed; below 10 years of age, in 5% of the patients single turn restoration was done and in 4% of the patients, 2 turn restoration was done. In the age group of 11 - 20 years, 2% have undergone single turn restoration in class III cavities, 5% have undergone two turn restoration and 0.2% has undergone three turn restoration. In the age group of 21 - 30 years, 6% have undergone single turn restoration, 13% have undergone two turn restoration and 1% has undergone three turn restoration. In the age group of 31-40 years, 9% have undergone single turn restoration, 12% have undergone two turn restoration and 0.8% has undergone three turn restoration. In the age group of 41 - 50 years, 8% have undergone single turn restoration in class III cavities, 12% have undergone two turn restoration and 1% has undergone three turn restoration. Above 50 years, 6% have undergone single turn restoration, 7% have undergone two turn restoration and 0.4% has undergone three turn restoration in class III cavities. Chi-square test was done and the p-value was found to be less than 0.01 (p-value <0.05, significant) (Figure 4). When the association between gender and the number of turns in class III restoration was analysed; in male patients, 13% have undergone class III restoration in single turn, 22% have undergone restoration in two turns and 1% have undergone restoration in three turns. In female patients, 25% have undergone restoration in single turn, 35% have undergone two turn restoration and in 1% of the patients, class III restoration was done in three turns. The p- value was found to be 0.168 and hence there was no significant difference in the association between gender and number of turns in restoration (Figure 5).

Figure 1. Bar graph representing the frequency of gender of patients who have undergone class III composite restoration with composite restoration. X axis represents the gender of the patients and Y axis represents the percentage of patients. The present study consists of 37% male patients and 62% of female patients.

Figure 2. Bar graph representing the frequency of age distribution of patients who have undergone class III composite restoration with composite restoration. X axis represents the age group of the patients and Y axis represents the percentage of patients.10% of the patients are below 10 years of age, 9% of the patients are between 11-20 years of age, 20% of the patients are between 21-30 years of age, 23% of the patients are below 31-40 years of age, 22% of the patients are between 41-50 years of age, 14% of the patients are above 50 years of age.

Figure 3. Bar graph representing the frequency of surface of class III restoration. X axis represents the surface of the restoration and the Y axis represents the number of patients. 27% of the patients have undergone class 3 mesial restoration and 72% have undergone class 3 distal restoration.

Figure 4. Bar graph representing the association between the age and number of turns of restoration in class III cavities. X axis represents the number of patients and Y axis represents the age of patients. Below 10 years, in 5% of the patients single turn restoration was done and in 4% of the patients, 2 turn restoration was done. In the age group of 11-20 years, 2% have undergone single turn restoration in class III cavities, 5% have undergone two turn restoration and 0.2% has undergone three turn restoration. In the age group of 21-30 years, 6% have undergone single turn restoration, 13% have undergone two turn restoration and 1% has undergone three turn restoration. In the age group of 31-40 years, 9% have undergone single turn restoration, 12% have undergone two turn restoration and 0.8% has undergone three turn restoration. In the age group of 41 - 50 years, 8% have undergone single turn restoration in class III cavities, 12% have undergone two turn restoration and 1% has undergone three turn restoration. Above 50 years, 6% have undergone single turn restoration, 7% have undergone two turn restoration and 0.4% has undergone three turn restoration in class III cavities. Chi - square test was done and the p - value was found to be less than 0.01 (p - value<0.05, significant).

Figure 5. Bar graph representing the association between the gender and the number of turns of restoration in class III cavities. X axis represents the number of patients and Y axis represents the gender of patients. In male patients, 13% have undergone class III restoration in single turn, 22% have undergone restoration in two turns and 1% has undergone restoration in three turns. In female patients, 25% have undergone restoration in single turn, 35% have undergone two turn restoration and in 1% of the patients, class III restoration was done in three turns. The p-value was found to be 0.168 (p-value<0.05, significant) and hence there was no significant difference in the association between gender and number of turns in restoration.

Discussion

Resin-bonded composite has undergone constant development of physical and mechanical properties in the last decade [32,33]. As a consequence, patient’s expectations for obscure dentistry have been increasing [34]. Dentists are expected to strictly adhere to the recreation of the morphology, texture and shade of the natural tooth. Previously, composite restoration systems were usually dependent on the use of single enamel and dentin which led to poor reproduction of the optical properties of natural teeth [35]. Hence, in recent times the vitality and depth of restorations have been achieved by the introduction of resin bonded composites based on natural layering techniques [35-37]. Dentin masses that reproduce the fluorescence of natural dentin and enamel to mimic the opalescence and translucence of natural enamel. Clinicians have to choose an appropriate layering technique and find the proper shade for restoring the teeth of young, adult and geriatric patients. Satisfactory results are obtained by Para mounting the integrity of restoration with the adjacent teeth and surrounding gingival tissues [38]. Class III restorations are considered as the most durable resin bonded composite restorations. This is attributed to several factors such as having a favorable C-factor, placed in low stress bearing areas and the cavity is usually surrounded by enamel. The results of this retrospective study state that the majority of patients who have undergone class III restoration were found to be in the age group of 31 - 40 years and when the gender comparison was done, majority of the class III restorations were done in females.

Conclusion

From the present study we can conclude that class III restoration was commonly performed in female patients and in the middle age group of 30 - 40 years.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank the University, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals for providing the required necessities for the present study.

Source of Funding

✓ Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Science, Saveetha University, India.

✓ Sree Balaji Enterprises.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there were no conflicts of interest in the present study.

References

- Sturdevant CM, Roberson TM. The art and science of operative dentistry. Mosby Elsevier Health Science 1995; 824.

- Fejerskov O, Kidd E. Dental caries: The disease and its clinical management. John Wiley & Sons 2009; 640.

- Kidd E. Essentials of dental caries: The disease and its management. 3rd Ed. The disease and its management. Oxford University Press 2005; 180.

- Schuurs A. Pathology of the hard dental tissues. John Wiley & Sons 2012.

- Zandona AF, Longbottom C. Detection and assessment of dental caries: A clinical guide. Springer Nature 2019; 249.

- Hudson AL. A study of the effects of mesiodistal reduction of mandibular anterior teeth. Ame J Orthod 1956; 42:615–624.

- Fontana M, Young DA, Wolff MS, et al. Defining dental caries for 2010 and beyond. Dent Clin North Am 2010; 54:423–440.

- Tanner T, Kämppi A, Päkkilä J, et al. Prevalence and polarization of dental caries among young, healthy adults: Cross-sectional epidemiological study. Acta Odontol Scandinavica 2013; 71:1436.

- Miletic V. Dental composite materials for direct restorations. Springer 2017; 319.

- Chin G, Chong J, Kluczewska A, et al. The environmental effects of dental amalgam. Aust Dent J 2000; 45:246–249.

- Hörsted-Bindslev P. Amalgam toxicity—environmental and occupational hazards. J Dent 2004; 32:359–365.

- Muthukrishnan L. Imminent antimicrobial bioink deploying cellulose, alginate, EPS and synthetic polymers for 3D bioprinting of tissue constructs. Carbohydr Polym 2021; 260:117774.

- PradeepKumar AR, Shemesh H, Nivedhitha MS, et al. Diagnosis of vertical root fractures by cone-beam computed tomography in root-filled teeth with confirmation by direct visualization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endod 2021; 47:1198–1214.

- Chakraborty T, Jamal RF, Battineni G, et al. A review of prolonged post-COVID-19 symptoms and their implications on dental management. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18.

- Muthukrishnan L. Nanotechnology for cleaner leather production: A review. Environ Chem Lett 2021; 19:2527–2549.

- Teja KV, Ramesh S. Is a filled lateral canal-A sign of superiority? J Dent Sci 2020; 15:562.

- Narendran K, Sarvanan A. Synthesis, characterization, free radical scavenging and cytotoxic activities of phenylvilangin, a substituted dimer of embelin. Indian J Pharm Sci 2020; 82:909-912.

- Reddy P, Krithikadatta J, Srinivasan V, et al. Dental caries profile and associated risk factors among adolescent school children in an Urban South-Indian City. Oral Health Prev Dent 2020; 18:379–386.

- Sawant K, Pawar AM, Banga KS, et al. Dentinal microcracks after root canal instrumentation using instruments manufactured with different NiTi alloys and the SAF system: A systematic review. Adv Sci Inst Ser E Appl Sci 2021; 11:4984.

- Bhavikatti SK, Karobari MI, Zainuddin SLA, et al. Investigating the antioxidant and cytocompatibility of Mimusops elengi Linn extract over human gingival fibroblast cells. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18.

- Karobari MI, Basheer SN, Sayed FR, et al. An In Vitro stereomicroscopic evaluation of bioactivity between neo MTA Plus, pro root MTA, biodentine & glass ionomer cement using dye penetration method. Materials 2021; 14.

- Rohit Singh T, Ezhilarasan D. ethanolic extract of lagerstroemia speciosa (l.) pers., induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in hepg2 cells. Nutr Cancer 2020; 72:146–156.

- Ezhilarasan D. MicroRNA interplay between hepatic stellate cell quiescence and activation. Eur J Pharmacol 2020; 885:173507.

- Romera A, Peredpaya S, Shparyk Y, et al. Bevacizumab biosimilar BEVZ92 versus reference bevacizumab in combination with FOLFOX or FOLFIRI as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: A multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 3:845–855.

- Raj RK. β‐Sitosterol‐assisted silver nanoparticles activates Nrf2 and triggers mitochondrial apoptosis via oxidative stress in human hepatocellular cancer cell line. J Biomed Material Res 2020; 108:1899-908.

- Vijayashree Priyadharsini J. In silico validation of the non-antibiotic drugs acetaminophen and ibuprofen as antibacterial agents against red complex pathogens. J Periodontol 2019; 90:1441.

- Priyadharsini JV, Vijayashree Priyadharsini J, Smiline Girija AS, et al. In silico analysis of virulence genes in an emerging dental pathogen A. baumannii and related species. Arch Oral Biol 2018; 94:93–98.

- Uma Maheswari TN, Nivedhitha MS, Ramani P. Expression profile of salivary micro RNA-21 and 31 in oral potentially malignant disorders. Braz Oral Res 2020; 34:e002.

- Gudipaneni RK, Alam MK, Patil SR, et al. Measurement of the maximum occlusal bite force and its relation to the caries spectrum of first permanent molars in early permanent dentition. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2020; 44:423–428.

- Chaturvedula BB, Muthukrishnan A, Bhuvaraghan A, et al. Dens invaginatus: A review and orthodontic implications. Br Dent J 2021; 230:345–350.

- Kanniah P, Radhamani J, Chelliah P, et al. Green synthesis of multifaceted silver nanoparticles using the flower extract of Aerva lanata and evaluation of its biological and environmental applications. Chemistry Select 2020; 5:2322–2331.

- Ma CF. Pink esthetic defects of restoration in anterior teeth and the treatment protocol. Chinese J Stomatol 2019; 54:378-81.

- Denehy GE. The importance of direct resins in dental practice. Pract Period Aesthet Dent 1999; 11:579–582.

- Haywood VB. Current status of nightguard vital bleaching. Compendium 2000; 21):10-17.

- Magne P, Belser U. Bonded porcelain restorations in the anterior dentition: A biomimetic approach. Quintessence Publishing 2002; 406. p.

- Dietschi D. Free-hand bonding in the esthetic treatment of anterior teeth: Creating the illusion. J Esthetic Restorative Dent 1997; 9:156–164.

- Spear FM, Kokich VG, Mathews DP. Interdisciplinary management of anterior dental esthetics. J Am Dent Assoc 2006; 137:160-169.

- Zalkind M, Heling I. Composite resin layering: An esthetic technique for restoring fractured anterior teeth. J Prosthet Dent 1992; 68:204.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Author Info

Haripriya R and Surendar Sugumaran*

Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences (SIMATS), Saveetha University, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, IndiaReceived: 26-May-2022, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-65010; , Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-65010 (PQ); Editor assigned: 28-May-2022, Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-65010 (PQ); Reviewed: 14-Jun-2022, QC No. JRMDS-22-65010; Revised: 17-Jun-2022, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-65010 (R); Published: 24-Jun-2022