Review Article - (2022) Volume 10, Issue 11

Coronavirus Disease 2019 and Gastrointestinal Manifestations

Kajal Bansal* and Sonali Choudhari

*Correspondence: Dr. Kajal Bansal, Department of Community Medicine, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences (Deemed to be University), Wardha, Maharashtra, India, Email:

Abstract

A severe Coronavirus infection is currently producing a worldwide pandemic. It has varied effects on different people. The majority of patients have a fever and a respiratory infection, but some may have diarrhoea, vomiting and stomach pain. The incubation period, on the other hand, might last anywhere from 2 to 14 days without causing any symptoms. It's especially true in the case of gastrointestinal symptoms, where the patient can continually shed the virus even after the lung symptoms have gone away. Given the high number of patients infected with Coronavirus disease 2019 WHO report with gastrointestinal symptoms, patients should be screened for gastrointestinal symptoms. Every organ must be identified since it has the ability to contribute to community health problems and plays significant role in illness monitoring and management. This quick overview's purpose is to keep you informed about the consequences of severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 infections on gastroenterology and hepatology departments, along with our new working techniques.

The goal of this study is to provide current information on Coronavirus disease 2019 symptoms in liver and gastrointestinal illnesses, as well as the pandemic's impact on prevention and treatment measures, with an emphasis on how existing procedures have been modified and what modifications may remain in the long term. This review provides gastroenterologists with new clinically relevant information.

Keywords

COVID-19 and gastrointestinal symptomatology, ACE2 receptor and COVID-19, COVID-19 on chronic liver disease, Liver injury

Abbreviations

GIT: Gastrointestinal Tract, ACE-2: Angiontensin Converting Enzyme 2, MERS: Middle East Respiratory Syndrome, SARS: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome, COVID-19: Coronavirus Disease 2019, CLD: Chronic Liver Disease, AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase, ALT: Alanine Aminotransferase, ESLD: End Stage Liver Disease, RTPCR: Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction

Introduction

SARS-CoV-2 is a single stranded RNA virus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome and belongs to the beta Coronavirus genus [1]. The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has resulted in the disease known as COVID-19 by the World Health Organization (WHO) [2]. It was thought to be a respiratory disease at first, but because the virus can affect other organs, including the gastrointestinal tract (the most frequent symptoms are anorexia and diarrhoea), feco oral transmission is a possibility in a number of contexts. The virus's effect on the liver is unknown, although it can imperil survival and cause decompensating in chronic liver disease patients, especially those in advanced stages. This review discusses the condition's major gastrointestinal components.

As of May 1, 2020, worldwide more than 3.3 million people had been suffered with Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), a respiratory ailment caused by a new Coronavirus Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Despite the fact that most occurrences of COVID-19 are moderate, the condition can be serious, leading to admissions to hospitals, respiratory failure, or death. Previous study from Wuhan suggested that 2% to 10% of COVID-19 patients experienced Gastrointestinal (GI) manifestations like diarrhoea, but a latest meta-analysis showed that roughly about 20% of COVID-19 infected persons had GI manifestations. Studies have found SARS-CoV-2 virus in anal and faeces specimen in over half of Corona patients, giving the impression of multiplication of virus in gastrointestinal tract and its impression outside of the lungs. Furthermore, fecalcalprotectin, an indication of inflammatory responses in the gut, was observed to be higher in patients of COVID-19 having diarrhoea. SARS-CoV-2 gets into the host via Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor, which is abundantly present in both the GI and respiratory systems. Profuse presentation of ACE2 in the epithelial cells of the gastrointestinal tract is also notified and the expression levels are even more than lung [3-5]. ACE2 has a crucial role in gut inflammation and microbial ecology. The gene regulation, metabolism and immune response are influenced by the gut flora which consists of massive amount of bacteria. Intruding viruses can modify the gut's commensal micro biota by either stimulating or suppressing the immune system. According to research, respiratory viral infections are correlated with alterations in the gut micro biota, which may make a person more susceptible patients to bacterial infections in the future. According to a latest Meta analytic review of broncho alveolar lavage fluid, microbes or upper respiratory commensal bacteria monopolised the micro biota in SARS-CoV-2 infected persons. Understanding the host microbial perturbations which underpin SARSCoV- 2 infection is critical, as they may alter infection response and the efficiency of future immunological treatments such as vaccinations [6].

Literature Review

While respiratory symptoms are common in COVID-19 infected individuals, some individuals also reported gastrointestinal manifestations such as diarrhoea, vomiting and abdominal discomfort as the illness progresses. Nausea, a loss of appetite and other symptoms are also common. The basic manifestations of COVID-19, which include olfactory and gustatory disturbances, have recently been expanded to include anosmia and dyspepsia [2]. In the United States, a 35-year-old man (the first case of COVID-19) who went to the hospital with two days of nausea and vomiting, followed by stomach pain and diarrhoea on the next day. On the seventh day of illness, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was discovered in the patient's faeces using a reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction. During the early outbreak, two adults were found to have diarrhoea (ages 36 and 37) out of six patients in a familial group of COVID-19 infections, with bowel habits as frequent as 8 times a day. In following cohorts, COVID-19 individuals have had gastrointestinal problems on a frequent basis. Anal/ rectal swabs were found to have viral RNA in over half of the cases, suggesting that this could be additional method of transmission and detection. Endoscopies of the digestive tract can create aerosols, which puts these procedures at risk of infection [3-6].

Patients may presents with GI problems earlier than normal in the phase of the illness, as evidenced by their ability to approach with them. The very 1st COVID-19 patients in the United States, for example, had nausea and vomiting two days before admission, followed by diarrhoea the next day [7]. The two young patients in the initial COVID-19 group, on the other hand, experienced diarrhoea when they arrived [8]. Diarrhoea is a common early symptom, and it can even appear before pyrexia or respiratory problems in few cases (Tables 1-3) [9,10].

| COVID-19 | Subject | Diarrhoea | Nausea | Vomiting | Abdominal pain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xiao F, et al. | 73 | 26 (35.6%) | NA | NA | NA |

| Wang D, et al. | 138 | 14 (10.1%) | 14 (10.1%) | 5 (3.6%) | 3 (2.2%) |

| Zhang JJ, et al. | 139 | 18 (12.9%) | 24 (17.3%) | 7 (5.0%) | 8 (5.8%) |

| Lu X, et al. | 171 | 15 (8.8%) | NA | 11 (6.4%) | NA |

| Zhou F, et al. | 141 | 9 (4.7%) | 7 (3.7%) | 7 (3.7%) | NA |

Table 1: Gastrointestinal symptoms in Coronavirus infection: COVID-19 (novel Coronavirus disease).

| SARS | Subject | Diarrhoea | Nausea | Vomiting | Abdominal pain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Booth CM, et al. | 144 | 34 (23.6%) | 28 (19.4) | 28 (19.4) | 5 (5.0%) |

| Cheng VC, et al. | 142 | 69 (48.6%) | NA | NA | NA |

| Leung WK, et al. | 138 | 53 (38.4%) | NA | NA | NA |

| Liu CL, et al. | 53 | 35 (66.0%) | 6 (11.3%) | 5 (9.4%) | 5 (9.4%) |

| Peiris JS, et al. | 75 | 55 (73.3%) | NA | NA | NA |

Table 2: Gastrointestinal symptoms in Coronavirus infection: SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus).

| MERS | Subject | Diarrhoea | Nausea | Vomiting | Abdominal pain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al Ghamdi M, et al. | 51 | 13 (25.5%) | NA | 12 (23.5%) | NA |

| Assiri A, et al. | 47 | 12 (25.5%) | 10 (21.2%) | 10 (21.2%) | 8 (17.0%) |

| Choi WS, et al. | 186 | 36 (19.4%) | 26 (14.0%) | 26 (14.0%) | 15 (8.1%) |

| Nam HS, et al. | 25 | 8 (32.0%) | 8 (32.0%) | 8 (32.0%) | 8 (32.0%) |

Table 3: Gastrointestinal symptoms in Coronavirus infection: MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus.

Symptoms of the gastrointestinal tract

MERS-CoV-2 patients exhibited a significant rate of gastrointestinal involvement: Diarrhoea (26%-33%), nausea (21%) and vomiting (21%-33%) observed. In eastern Saudi Arabia, they investigated GI symptoms in 35% of the patients [11].

Interestingly, few studies are reporting cases with gastrointestinal symptoms earlier than respiratory involvement, with some cases only exhibiting GI symptoms without involvement of respiratory system [12-14].

Other GI signs and symptoms

In patients with severe illness, major gastrointestinal manifestation such as bloody diarrhoea is often likely. Other GI signs include constipation and haemorrhagic colitis. Several round herpetic erosions and ulcers are found during an endoscopic examination of a patient of COVID-19 with gastrointestinal bleeding. In individuals with significant symptoms, ulcerative and ischemic alterations seen in rectosigmoidoscopy [15].

An atypical symptom was reported in a 71 year old female, who, after a trip to Egypt, presented with haemorrhagic colitis without respiratory involvement. She tested positive on nasopharyngeal PCR for SARSCoV- 2. After being investigated for various causes of haemorrhagic colitis, the reason for her lower GI bleed was found to be the SARS-CoV-2 [16]. One more case report of 41 year old woman from Michigan (United States), who presented with voluminous diarrhoea and electrolyte imbalance before appearance of respiratory symptoms, suggests that COVID-19 can have variable gastrointestinal picture [17].

Although unusual, these manifestations can cause delay in diagnosis if physicians are not aware with gastrointestinal manifestations of Coronavirus [18]. However, it is uncertain that how these rare manifestations would impact clinical course and prognosis.

The onset of GI symptoms might happen at any time. They appear during the beginning of the disease (before any other clinical symptoms), but in most of the cases, they appear later. Only 11.6percent of COVID-19 patients had gastrointestinal manifestation when they were admitted to the hospital, with the rest acquiring symptoms later. Those suffering from gastrointestinal issues were admitted to the hospital far later than those suffering from respiratory problems. As a result, there was a delay in diagnosis and treatment. Patients with gastrointestinal manifestations were expected to arrive late to the hospital and obtain an incorrect diagnosis. When compared to non-GI counterparts, their clinical course was more erratic, with a higher frequency of severe illness progression (requiring mechanical ventilation and ICU treatment). They had to stay in the hospital longer because their discharge had been delayed until the infection had been cleared. This result might be due to a number of factors. While a delay in treatment may have had a role, studies reveal that persons who experience GI symptoms have greater viral replication and levels. Because they exhibited greater chances of faecal RT-PCR positive than the overall population, patients with gastrointestinal symptoms should have routine Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR) testing. Moreover, no relationship has been shown in several investigations among both positive PCR findings and the occurrence of GI manifestation or the seriousness of the condition. Ethnic/geographical variances, concurrent comorbidities, or the adoption of differing clinical and diagnostic criteria might all contribute to variations in GI indicators and onset time. It's critical to be conscious of the vast spectrum of gastrointestinal manifestation related with COVID-19 so that this possibility can be looked into right away. Physicians should be on the lookout for patients with pyrexia and gastrointestinal manifestations, since this might be the only predictor of COVID-19, signifying the onset of a severe illness with life threatening effects. Beyond the pre-existing liver disease, there were no other known risk factors for the development of GI symptoms, making the prognostic value of developing such clinical signs complicated [19-21].

Discussion

Mechanisms involving the gastrointestinal tract

After virus entry, virus specific RNA and proteins are generated in the cytoplasm, to form new virions that may be discharged into the GI tract. A viral infection can lead to change in intestinal permeability, leading to enterocyte malfunction [22-28]. The existence of viral RNA in stools on regular basis shows that infectious virions are released by gastrointestinal cells infected with virus. Infectious SARS-CoV-2 had been lately found through faeces, indicating that infectious virions were released into the gastrointestinal system. As a result, faecal oral transmission might be another way for viruses to propagate. To reduce the spread of the virus, avoidance of faecal oral transmission must be considered [29].

Because human intestinal epithelial cells are particularly sensitive for the virus and may undergo vigorous viral multiplication, MERS-CoV-2 could cause enteric illness. This gastrointestinal tropism could explain why Coronavirus infections are so common. Fomite transmission can be aided by this faecal source,particularly when infective aerosols are produced by the toilet plume [30].

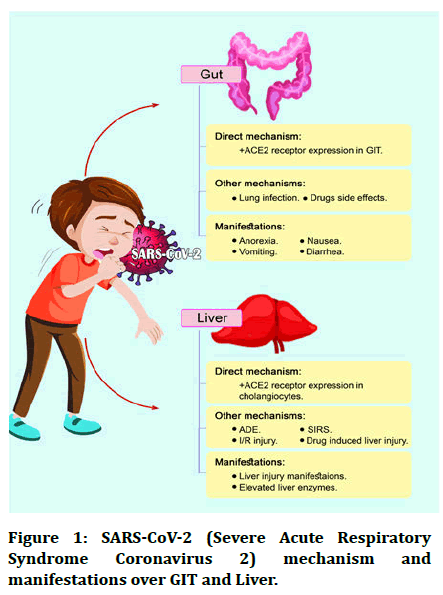

Coronavirus has a propensity for the gastrointestinal tract, according to previous studies. In stool samples from SARS patients, SARS-CoV-2 RNA was discovered, and in both the small and large intestines, electron microscopy of biopsy and autopsy materials revealed active viral multiplication. ACE2 is expressed in abundance throughout the gastrointestinal tract, particularly in the small and large intestines, and type II alveolar cells (AT2) in the lungs [31,32]. SARS-CoV-2 infects GIT through its viral receptor ACE2, which is found on enterocytes in the colon and ileum. In humans, the ACE2 receptor is involved in amino acid homeostasis, the gut micro biome, and innate immunity. SARS-CoV-2 binding to ACE2 in the GI tract may generate GIT symptoms as a result. ACE2 are significantly expressed in patients with pre-existing colorectal cancer or adenomas as compared to healthy controls, but whether they have a higher risk of infection is unknown (Figure 1).

Figure 1: SARS-CoV-2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2) mechanism and manifestations over GIT and Liver.

Injuries to the liver in COVID-19 patients

In COVID-19, liver involvement is usually moderate and does not need treatment [33]. The ethology of liver damage is unknown; however it might be hepatocyte viral infection, immune related harm, or medication toxicity. By adhering to cholangiocytes via the ACE2 receptor, the virus may be able to affect liver function. Previous studies have depicted that ACE2 is highly presented over hepatocytes (2.6%), cholangiocytes (59.7%) and liver endothelial cells [34,35]. Hepatocytes have less ACE2 receptors than cholangiocytes. In the liver of a deceased COVID-19 patient, histological testing revealed micro vesicular steatosis and modest lobular activity. SARS-CoV-2 infection or drug induced liver damage might be the source of these histological alterations. Despite this, there was no sign of viral inclusion in the liver. It's still unknown if SARS-CoV-2 targets the liver in the same way as SARS-CoV-2 does, or if it employs distinct methods to destroy the liver.

Patients of COVID-19 can develop liver damage as well as gastrointestinal problems, as evidenced by increased enzymes in blood tests. Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels were abnormal in COVID-19 patients, and blood bilirubin levels were typically modestly elevated [20,36]. Though serious liver damage is conceivable, most liver injuries are minor and only last a few days. People with acute COVID-19 disease also had a higher risk of liver damage. COVID-19 had one critical patient with acute hepatitis, having blood ALT levels approaching 7590 U/L, whereas the Wuhan group had 43 patients with elevated ALT or AST values.

It is still not clear that whether patients with previous Chronic Liver Disease (CLD) having Coronavirus manifested with different clinical picture from those who are not having CLD. Outcomes in CLD cases with SARSCoV- 2 infection are still being collected and shows higher chances of mortality, and these risk increases with severity of liver disease such as increased child turcotte Pugh score and End Stage Liver Disease (ESLD) [37-39].

There have been no reports of acute liver failure. When individuals come with a more severe condition, they are more likely to have liver impairment. It's hard to tell the difference between the independent effect of viral infection and the innumerable forms of treatment used in these patients, such as antibiotics and experimental antiviral medicines. These changes could also be generic anomalies caused by infection, hypoxia or sepsis. Other laboratory disturbances like creatinine kinase, thrombocytopenia and leukopenia were even more prevalent in individuals who have been worse at the time of diagnosis or died. Except for one case who received an autopsy, which revealed micro vesicular steatosis and mild lobular and portal inflammation on liver histology, there is no data on liver pathology [40].

Consequences for patient care and infection prevention

The SARS-CoV-2 gastrointestinal tropism, positive stool detection and the GI symptoms it causes have serious consequences for patient safety and infection control. Physicians should be aware of COVID-19's GI effects, which might manifest before pyrexia and respiratory issues. SARS-CoV-2 RNA was discovered in the faces of 39 (53.4%) of 73 COVID-19 patients in a study, with positive stool lasting one to twelve days. Despite the fact that lung samples were negative, 17 (23.3%) people had high quantities of stool virus RNA in their systems [41]. In a separate trial that followed 10 children and analysed both nasopharyngeal and rectal swabs, 8 children screened positive on colorectal swabs even after nasopharyngeal eradication of the virus [42,43]. Furthermore, viral RNA has been found in the faces or anal/rectal swabs of COVID-19 patients in several studies [44-46]. Following clearing with two positive rectal swabs, two children had two consecutive negative rectal swabs separated by at least 24 hours. In contrast to the Cycle Threshold (Ct) value of 36–38 on having an illness, the longitudinal Ct values in youngsters were frequently less than. Stool samples from the first US taken on day 7 revealed that viral transmission through the GI system can be widespread and continue long after clinical symptoms have disappeared. In fact, a prior research of SARS-CoV-2 identified viral RNA in the faces of SARS patients 30 days after infection [47-58].

Summary

The dynamics of SARS viral CoV-2 in the GI system, on the other hand, are unknown and may differ from those in the respiratory tract. According to a recent environmental experiment, SARS-CoV-2 might live for hours in aerosols and at least 72 hours on plastic and stainless steel. While additional study is needed to determine its replication potential, the presence of SARS abundant CoV-2 in faces and the environmental stability would favour its dissemination among human hosts. The virus remained longer and achieved peak viral load later in contrast to respiratory samples; the virus load peaked between the third and fourth weeks after the sickness began. The evolution of GI symptoms is crucial to be aware of because they could be one of the earliest signs of COVID-19 infection. COVID-19 diagnosis may be problematic due to the presence of early GI symptoms, which may deceive clinicians.

Conclusion

SARS-CoV-2 is a global epidemic that has killed a lot of people. The prognosis of patients with comorbidities is poor. As the disease's natural history and range of clinical manifestations have developed, extra pulmonary signs of COVID-19 have surfaced. Because of COVID-19's gastrointestinal involvement, a variety of clinical interventions would need to be explored, including rectal swab testing before patients were discharged and our readiness for personal protective equipment in the endoscopic situation. As a result, doctors should be aware of gut symptomatology, which can occur before pyrexia or respiratory symptoms appear. Even if no respiratory symptoms are evident, COVID-19 infection is connected to a variety of gastrointestinal symptoms. As a result, people who have a lot of gastrointestinal problems might look into COVID-19. Because viral RNA can be found in faces, a faecal test may be positive even if respiratory samples are negative. These factors will be crucial in our fight against COVID-19. Further studies in future will help in better understanding the gastrointestinal manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to the authors of literature involved in this article for their contribution to fight against Coronavirus.

References

- Wong SH, Lui RN, Sung JJ. COVID‐19 and the digestive system. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 35:744-748.

- Hunt RH, East JE, Lanas A, et al. COVID-19 and gastrointestinal disease: Implications for the gastroenterologist. Dig Dis 2021; 39:119-139.

- Cipriano M, Ruberti E, Giacalone A. Gastrointestinal infection could be new focus for Coronavirus diagnosis. Cureus 2020; 12:e7422.

- Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis ML, et al. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS Coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol 2004; 203:631-637.

- Jiao L, Li H, Xu J, et al. The gastrointestinal tract is an alternative route for SARS-CoV-2 infection in a non-human primate model. Gastroenterology 2021; 160:1467-1469.

- Tao Zuo, Fen Zhang, Lui GCY, et al. Alterations in gut micro biota of patients with COVID-19 during time of hospitalization. Gastroenterol 2020; 159:944-955.

- Chu H, Fuk-Woo Chan J, et al. SARS-CoV-2 induces a more robust innate immune response and replicates less efficiently than SARS-CoV in the human intestines: An ex vivo study with implications on pathogenesis of COVID-19. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2021; 11:771-781.

- Rousset S, Moscovici O, Lebon P, et al. Intestinal lesions containing Coronavirus like particles in neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis: An ultra-structural analysis. Pediatrics 1984; 73:218–224.

[Crossref][Googlescholar][Indexed ]

- Resta S, Luby JP, Rosenfeld CR, et al. Isolation and propagation of a human enteric Coronavirus. Science 1985; 229:978-981.

- Tang A, Tong ZD, Wang HL, et al. Detection of novel Coronavirus by RT-PCR in stool specimen from asymptomatic child, China. Emerg Infect Dis 2020; 26:1337-1339.

- Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of Coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:1708-1720.

- Tran J, Glavis Bloom J, Bryan T, et al. COVID-19 patient presenting with initial gastrointestinal symptoms. Euro Rad 2020; 16654.

- Wang S, Guo L, Chen L, et al. A case report of neonatal COVID-19 infection in China. Clin Infect Dis 2020: 71:853-857.

- An P, Chen H, Jiang X, et al. Clinical features of 2019 novel Coronavirus pneumonia presented gastrointestinal symptoms but without fever onset. 2020.

- Lu X, Zhang L, Du H, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection in children. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:1663-1665.

- Carvalho A, Alqusairi R, Adams A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 gastrointestinal infection causing haemorrhagic colitis: Implications for detection and transmission of COVID-19 disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2020; 115:942-946.

- Cappell M. Severe diarrhoea and impaired renal function in COVID-19 disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2020; 115:947-948.

- Han C, Duan C, Zhang S, et al. Digestive symptoms in COVID-19 patients with mild disease severity: Clinical presentation, stool viral RNA testing and outcomes. Am J Gastroenterol 2020; 115:916-923.

- Xu XW, Wu XX, Jiang XG, et al. Clinical findings in a group of patients infected with the 2019 novel Coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) outside of Wuhan, China: Retrospective case series. BMJ 2020; 368:m606.

- Zhou J, Li C, Zhao G, et al. Human intestinal tract serves as an alternative infection route for Middle East respiratory syndrome Coronavirus. Sci Adv 2017; 3:eaao4966.

- Kariyawasam JC, Jayarajah U, Riza R, et al. Gastrointestinal manifestations in COVID-19. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2021; 115:1362-1388.

- Chakraborty S, Basu A. The COVID-19 pandemic: Catching up with the cataclysm. F1000Res 2020; 9:638.

- Parasa S, Desai M, Thoguluva Chandrasekar V, et al. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms and faecal viral shedding in patients with Coronavirus disease 2019: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3:e2011335.

- Kopel J, Perisetti A, Gajendran M, et al. Clinical insights into the gastrointestinal manifestations of COVID-19. Dig Dis Sci 2020; 65:1932-1939.

- Xiong LJ, Zhou MY, He XQ, et al. The role of human Coronavirus infection in paediatric acute gastroenteritis. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2020; 39:645–649.

- Li RL, Chu SG, Luo Y, et al. A typical presentation of SARS-CoV-2 infection: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8:1265-1270.

- Lin L, Jiang X, Zhang Z, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms of 95 cases with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Gut 2020; 69:997-1001.

- Jin X, Lian JS, Hu JH, et al. Epidemiological, clinical and virological characteristics of 74 cases of Coronavirus infected disease 2019 (COVID-19) with gastrointestinal symptoms. Gut 2020; 69:1002-1009.

- Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel Coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet 2020; 395:507-513.

- Xiao F, Tang M, Zheng X, et al. Evidence for Gastrointestinal Infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterol 2020; 158:1831-1833.

- Pan L, Mu M, Yang P, et al. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 patients with digestive symptoms in Hubei, China: A descriptive, cross sectional, multicentre study. Am J Gastroenterol 2020; 115:766-773.

- Huang C, Wang Y, Li X et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel Coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020; 395:497–506.

- Bangash MN, Patel J, Parekh D. COVID-19 and the liver: Little cause for concern. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 5:529-530.

- Chai X, Hu L, Y. Zhang. Specific ACE2 expression in cholangiocytes may cause liver damage after 2019-nCoV infection. BioRxiv 2020.

- Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis ML, et al. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS Coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol 2004; 203:631-637.

- Han C, Duan C, Zhang S, et al. Digestive symptoms in COVID-19 patients with mild disease severity: Clinical presentation, stool viral RNA testing and outcomes. Am J Gastroenterol 2020; 115:916–923.

- Iavarone M, D'Ambrosio R, Soria A, et al. High rates of 30-day mortality in patients with cirrhosis and COVID-19. J Hepatol 2020; 73:1063-1071.

- Moon AM, Webb GJ, Aloman C, et al. High mortality rates for SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with pre-existing chronic liver disease and cirrhosis: Preliminary results from an international registry. J Hepatol 2020; 73:705-708.

- Marjot T, Moon AM, Cook JA, et al. Outcomes following SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with chronic liver disease: An international registry study. J Hepatol 2021; 74:567-577.

- Agarwal A, Alan C, Ravindran N, et al. Thuluvath, gastrointestinal and liver manifestations of COVID-19. J Clin Exp Hepatol 2020; 10:263-265.

- Harmer D, Gilbert M, Borman R, et al. Quantitative mRNA expression profiling of ACE 2, a novel homologue of angiotensin converting enzyme. FEBS Lett 2002; 532:107-110.

- Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok KH, et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel Coronavirus indicating person to person transmission: A study of a family cluster. Lancet 2020; 395:514–523.

- Villapol S. Gastrointestinal symptoms associated with COVID-19: Impact on the gut micro biome. Transl Res 2020; 226:57-69.

- Xiao F, Tang M, Zheng X, et al. Evidence for gastrointestinal infection of SARS-CoV-2. Gastroenterol 2020; 158:1831-1833.

- Zhang W, Du RH, Li B, et al. Molecular and serological investigation of 2019-nCoV infected patients: Implication of multiple shedding routes. Emerg Microbes Infect 2020; 9:386-389.

- Xu Y, Li X, Zhu B, et al. Characteristics of paediatric SARS-CoV-2 infection and potential evidence for persistent fecal viral shedding. Nat Med 2020; 26:502-505.

- Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, et al. First case of 2019 novel Coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:929–936.

- Zhang JJ, Dong X, Cao YY, et al. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy 2020; 75:1730-1741.

- Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020; 395:1054-1062.

- Booth CM, Matukas LM, Tomlinson GA, et al. Clinical features and short term outcomes of 144 patients with SARS in the greater Toronto area. JAMA 2003; 289:2801-2809.

- Cheng VC, Hung IF, Tang BS, et al. Viral replication in the naso pharynx is associated with diarrhoea in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 38:467-475.

- Leung WK, To KF, Chan PK, et al. Enteric involvement of severe acute respiratory syndrome associated Coronavirus infection. Gastroenterol 2003; 125:1011–1017.

- Liu CL, Lu YT, Peng MJ, et al. Clinical and laboratory features of severe acute respiratory syndrome vis a vis onset of fever. Chest 2004; 126:509–517.

- Peiris JS, Chu CM, Cheng VC, et al. Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of Coronavirus associated SARS pneumonia: A prospective study. Lancet 2003; 361:1767-1772.

- Al Ghamdi M, Alghamdi KM, Ghandoora Y, et al. Treatment outcomes for patients with Middle Eastern respiratory syndrome Coronavirus (MERS CoV-2) infection at a Coronavirus referral centre in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. BMC Infect Dis 2016; 16:174.

- Assiri A, Al Tawfiq JA, Al Rabeeah AA, et al. Epidemiological, demographic and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome Coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: A descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13:752–761.

- Choi WS, Kang CI, Kim Y, et al. Clinical presentation and outcomes of middle east respiratory syndrome in the republic of Korea. Infect Chemother 2016; 48:118-126.

- Nam HS, Park JW, Ki M, et al. High fatality rates and associated factors in two hospital outbreaks of MERS in Daejeon, the republic of Korea. Int J Infect Dis 2017; 58:37-42.

Author Info

Kajal Bansal* and Sonali Choudhari

Department of Community Medicine, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, Datta Meghe Institute of Medical Sciences (Deemed to be University), Wardha, Maharashtra, IndiaCitation: Kajal Bansal, Sonali Choudhari, Coronavirus Disease 2019 and Gastrointestinal Manifestations, J Res Med Dent Sci, 2022, 10 (11): 223-229.

Received: 29-Aug-2022, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-75565 ; , Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-75565 (PQ); Editor assigned: 01-Sep-2022, Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-75565 (PQ); Reviewed: 15-Sep-2022, QC No. JRMDS-22-75565 ; Revised: 31-Oct-2022, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-75565 (R); Published: 08-Nov-2022