Research - (2020) Volume 8, Issue 6

Increasing Collaboration between Dentistry and Medicine

Timothy G Donley1, Kristopher S Pfirman2*, Mohammed Kazimuddin2 and Aniruddha Singh2

*Correspondence: Kristopher S Pfirman, Department of Cardiology, The Medical Center-Bowling Green Western Kentucky Heart, United States, Email:

Abstract

The most common form of periodontal disease is chronic inflammatory periodontal disease (CIPD). CIPD, a multifactorial disease, begins with a microbial infection on tooth surfaces, followed by a host mediated destruction of adjacent tissues. It is well accepted in medicine that inflammation plays a contributory role in cardiovascular disease (CVD). Interventional therapy to reduce CVD risk includes reducing sources that are contributing to the burden of systemic inflammation. Medical health care providers who care for patients with the systemic diseases potentially affected by oral inflammation, including those with known risk factors, must alter existing examination protocols to include realistic, time-efficient screening for oral inflammation and then appropriate referral to dental providers for definitive diagnosis and therapy. A system to screen patients for the potential for having oral inflammation may be the most realistic option to achieve the best overall wellness for our patients by integration and collaboration.

Condensed abstract: The most common form of periodontal disease is chronic inflammatory periodontal disease (CIPD). Medicine has long recognized that increased levels of systemic inflammation play a role in the development and progression of many of the chronic diseases. A medical screening medical/dental collaborative checklist should include the medical conditions that are potentially affected by oral inflammation. The two-way relationship between periodontal and systemic diseases suggests that there are distinct patient categories that would benefit from medical screening for potential oral inflammation.

Keywords

Periodontal disease, Inflammation, Prevention, Acute coronary syndrome, Coronary artery disease, Cardiovascular disease

Bullet Point Highlights

Inflammation plays a contributory role in both chronic inflammatory periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease.

Screening tools at bedside/chairside should be implemented to identify at risk individuals for referral.

Collaboration between medical and dental professionals should be employed to reduce systemic inflammation burden.

Abbreviation List

CIPD=Chronic Inflammatory Periodontal Disease, CVD=Cardiovascular Disease, BOP=Bleeding on Probing, BMI=Body Mass Index, A1c=Hemoglobin A1c, COPD=Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease,

Following is the detailed study.

Introduction

The most common form of periodontal disease is chronic inflammatory periodontal disease (CIPD). CIPD, a multifactorial disease, begins with a microbial infection on tooth surfaces, followed by a host mediated destruction of adjacent tissues. The current paradigm suggests that periodontitis represents a dysregulation of the host response to a dysbiotic microbiome which occurs is a large part of the global population. Cells that mediate inflammation generate cytokines, eicosanoids, and matrix metalloproteinases that cause clinically significant connective tissue and bone destruction [1,2]. Cytokine induced destruction of collagen leads to not only the loss of the investing bone, but also damage to the connective tissue supporting the lining epithelium approximating the tooth. In this typical periodontal lesion, the integrity of the lining epithelium is compromised allowing bacteria, bacterial by-products and the cytokines released in response to the initiating bacteria to penetrate regularly through the ulcerated epithelium into the bloodstream [3,4].

Medicine has long recognized that increased levels of systemic inflammation play a role in the development and progression of many of the chronic diseases of aging [5] and that controlling systemic inflammation can reduce the development and progression of many of the quality-of-life affecting chronic diseases of aging [6]. There is now undeniable evidence that the local inflammatory response to initiating periodontal biofilm spills into the circulatory system and contributes to the level of systemic inflammation [3,7]. Not surprisingly, emerging data continues to indicate that periodontal diseases may also be associated with a wide array of systemic diseases [8].

Despite overwhelming evidence that oral inflammation contributes to the systemic burden of inflammation, some in dentistry continue to suggest that any discussion of an oral-systemic link should be muted due to a lack of proof [9,10]. Establishing proof of causality between inflammation of oral origin and any of the associated inflammation-driven chronic diseases will continue to be challenging. To establish proof, it will be necessary to quantify the specific level of inflammation of oral origin that contributes to the systemic inflammatory burden. Currently, dentistry is reliant on bleeding upon gentle probing of the periodontal environment (BOP). While BOP is an excellent predictor of inflammation in the adjacent soft tissues, it is binary and indicates only the presence or absence of inflammation. Until clinical measurements of the quality and quantity of oral inflammation initiated by biofilm are available, evidence of proof of a link between oral and systemic diseases will remain elusive.

While the search for proof of causality continues, it may be more useful clinically, (and vitally important to patients who are susceptible to inflammatory-driven systemic diseases), to consider the potential for inflammation of oral origin to contribute to system disease risk.

It is well accepted in medicine that inflammation plays a contributory role in cardiovascular disease (CVD). Interventional therapy to reduce CVD risk includes reducing sources that are contributing to the burden of systemic inflammation [11]. The consensus from a recent world workshop evaluating the relationship between periodontal and cardiovascular diseases included a recommendation that, “people with CVD must be aware that gum disease is a chronic condition, which may aggravate their CVD, and requires lifelong attention and professional care” [12].

It is reasonable to put oral inflammation on the list of contributing factors to the systemic burden of inflammation [13]. Periodontal therapy has the potential to reduce markers of systemic inflammation in a clinically significant manner [14-17]. Many of the risk factors for periodontal disease are also risk factors for other inflammatory-associated diseases [18,19]. Integration of dentistry and medicine is critical for best management of the diseases that both disciplines share. Successful integration requires the focus of dentistry and medicine to be expanded beyond traditional boundaries. Those boundaries need to change so that comanagement of risk factors can enhance the level of wellness for every patient. Co-managing the risk factors common to oral and systemic diseases can only improve the management of dental and medical diseases that have traditionally been managed separately.

Limiting the goal of dental therapy to simply helping patients keep their teeth is inadequate. The new goal of dentistry must be to help patients achieve and then maintain a functional and esthetic dentition that can be maintained relatively inflammation-free over their lifespan, not only for the oral health benefits but to reduce their overall level of systemic inflammation and therefore supporting overall wellness. Dental professionals must be consistently adequate in diagnosing and eliminating oral inflammation. Dental visits provide opportunities for dental providers to screen for the risk factors that are common to both periodontal and systemic diseases. With so many dental patients enrolled in regular visits during the maintenance phase of dentistry, dental practitioners can also assist medicine by educating, motivating and supporting patients in adopting the risk factor modifications necessary to reduce systemic as well as local inflammation.

Medicine must expand its oral diagnostic capabilities for the integration of medicine and dentistry to reach its potential. Medical health care providers who care for patients with the systemic diseases potentially affected by oral inflammation (or even patients simply with risk factors for these systemic diseases) must alter existing examination protocols to include realistic, time-efficient screening for oral inflammation and then appropriate referral to dental providers for definitive diagnosis and therapy. To date, no standard protocol for oral screening by non-dental personnel exists.

Medical personnel awareness of oral health and signs of oral diseases is limited [20]. Too often, the medical assessment of oral status is limited to a tongue-blade assisted cursory glance at the entrance to the oral cavity, or a question or two as to the oral hygiene habits of the patient. The typical components of a comprehensive dental evaluation, (full periodontal charting, review of radiographs, clinical examination, etc.) is not realistic in most medical settings. The health care integration challenge for dentistry is to provide medicine with a screening protocol that is effective, yet involves minimal time, equipment, and effort. Periodontal disease is a systemic disease with site specific presentation [21].

Diagnosis typically involves a combination of probing depth, attachment loss, bleeding upon probing, radiograph evidence of bone loss and/or presence of detectible etiology [22], all of which are surrogate markers of inflammatory induced periodontal destruction. One of the ongoing difficulties in periodontal diagnosis is the lack of easily attainable and quantifiable measurements of both the pathogenic potential of the biofilm load and the resultant inflammatory response.

In the dental setting, bleeding following probing remains the most reliable indicator of subgingival inflammation albeit with only moderate sensitivity and higher specificity [23]. While the presence of bleeding following probing is not overly predictive of oral inflammation at that site, the absence of bleeding is more strongly correlated with an absence of inflammation. Thus, bleeding following probing is far from an ideal screening tool but may be more useful when determining therapeutic outcomes. It is binary and does not provide any quantitative assessment of oral inflammation. Bleeding on probing is also time-consuming and technique sensitive. The threshold number of sites with detected oral inflammation necessary to impact the systemic burden of inflammation has never been definitively determined [24].

What is needed is a screening tool that affords both medical and dental personnel an easy, reliable chairside analysis of patients’ oral inflammatory burden. Oral inflammation is commonly symptomless, rarely leads to spontaneous bleeding, and is often characterized by subtle clinical changes of which most patients are unaware and unable to recognize [25]. Screening visually for the subtle clinical signs of inflammation, questioning patients as to periodontal symptoms, or obtaining evidence of oral inflammation via probing is far from realistic in medical settings. However, indices have been developed for bleeding following interproximal stimulation with a properly sized interproximal brush. This could provide a reasonable alternative to actual periodontal probing [26]. Equipping medical health care settings with diagnostic interproximal brushes and education as to how to use the brush to screen for oral inflammation does seem feasible. A system to screen patients for the potential for having oral inflammation may be the most realistic option. The consequences of biofilm accumulation in a particular individual are influenced by various well-established risk factors for CIPD, which are also common to other systemic diseases, including genetic and epigenetic influences, tobacco use, obesity, nutrition, exercise, hypertension, dyslipidemia, psychosocial stress, depression, sleep disorders, excessive alcohol consumption, changes in bone metabolism, low socioeconomic status, poor oral hygiene, increased age, and Hispanic ethnicity [27]. It seems reasonable to design a protocol in which medical and dental providers can use a yes/no checklist to determine if their patients have any of these identifiable risk factors for periodontal disease. Those patients who do have identifiable risk factors for periodontal disease should receive a more comprehensive oral evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment plan by a dental provider.

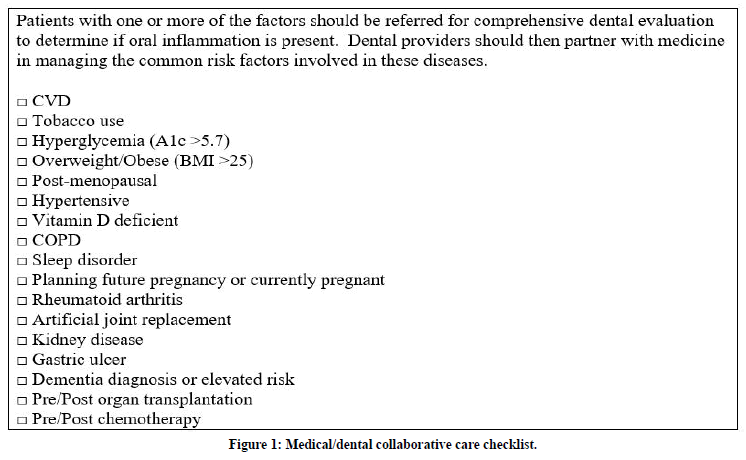

A medical screening checklist should also include the medical conditions that are potentially affected by oral inflammation. The two-way relationship between periodontal and systemic diseases suggests that there are distinct patient categories that would benefit from medical screening for potential oral inflammation. Current evidence suggests that patients being followed in medicine for cardiovascular disease [28], diabetes [29], rheumatoid arthritis [30], post-menopausal ramifications [31], respiratory ailments [32], solid organ transplantation [33], kidney diseases [34], gastric ulcers [35], dementia risk management, [36], artificial joint replacement [37], pre-natal care [38], and certain cancers [39], could benefit for identification and timely elimination of oral inflammation. At the very least, medical screening and then dental referral of patients in these categories seems prudent considering the potential benefits to patient outcomes. Evidence is emerging suggesting that eliminating oral inflammation in patients can result in significant long-term health care cost savings as well [40].

True assessment of the effect that inflammation of oral origin has on specific systemic conditions will require an objective measurement of the oral inflammatory burden present in an individual patient or of the pathogenic potential of the initiating oral bacterial accumulation. Until such screening methods are designed, a medical screening for oral inflammation checklist encompassing those patients with risk factors for periodontal disease and for those patients in whom oral inflammation has potential effects on systemic health is listed in Figure 1. Ideally, medical, and dental personnel, when evaluating patients presenting for care, would use this checklist. An affirmative answer to any question would signal the need for more comprehensive dental evaluation. Since any category on the list indicates a need for further evaluation, once an affirmative answer was noted and referral was suggested, the remainder of the form would not need to be completed [41].

Figure 1. Medical/dental collaborative care checklist.

Ideally, stakeholders in healthcare should strive to develop a reliable, quick, minimally invasive, and cost-effective test with acceptable sensitivity/ specificity for either the pathogenic potential of the inflammation-initiating biofilm and/or to quantify the actual local inflammation response. For example, an easily obtained swab sample of oral fluid that could be analyzed chairside for pathogen or inflammatory mediator load would be an ideal solution to the challenge of medical personnel screening for oral inflammation.

The patient and healthcare cost benefits from co-management of diseases with medicine is compelling. The potential for including a developed screening tool/method into health care facilities worldwide is enormous. Clearly, it is time for all of healthcare to usher in a new era of medical and dental collaboration to help patients achieve the highest possible levels of wellness.

Acknowledgments

Melinda Joyce, PharmD,

The Medical Center–Bowling Green, United Sates

Doug McElroy, PhD

Department of Biology, Western Kentucky University, Western Kentucky Heart, Lung, and Gastroenterology, United States

Funding

Quick Turnaround Grant - $3000

Western Kentucky University

Bowling Green, KY, 42101

Special Grant Program - $4996

Kentucky Academy of Science

Louisville, KY 40202

References

- Huang N, Gibson FC. Immuno-pathogenesis of periodontal disease: Current and emerging paradigms. Curr Oral Health Rep 2014; 1:124–132.

- Kornman KS, Page RC, Tonetti MS. The host response to the microbial challenge in periodontitis: Assembling the players. Periodontol 1997; 14:33-53.

- Tomas I, Diz P, Tobıas A, et al. Periodontal health status and bacteraemia from daily oral activities: Systematic review/meta-analysis. J Clin Periodontol 2012; 39:213–228.

- Reyes L et al. Periodontal bacterial invasion and infection: Contribution to atherosclerotic pathology. J Clin Periodontol 2013; 40:30-50.

- El-Shinnawi U, Sorry M. Associations between periodontitis and systemic inflammatory diseases: Response to treatment. Recent Pat Endocr Metab Immune Drug Discov 2013; 7:169-188.

- Aksentijevich M, Lateef SS, Anzenberg P, et al. Chronic inflammation, cardiometabolic diseases and effects of treatment: Psoriasis as a human model. Trends Cardiovasc Med 2019; 19:30151-30153.

- Cardoso EM, Rei C, Manzanares-Céspede MC. Chronic periodontitis, inflammatory cytokines, and interrelationship with other chronic diseases. Postgrad Med 2018; 130:98–104.

- Nagpal R, Yamashiro Y, Izumi Y. The two-way association of periodontal infection with systemic disorders: An overview. Mediators Inflammation 2015; 2015:1-9.

- Pihlstrom B, Hodges S, Michalowicz B, et al. Promoting oral health care because of its possible effect on systemic disease is premature and may be misleading. J Am Dent Assn 2018; 149:401–403.

- Lavigne S, Forrest J. An umbrella review of systematic reviews of the evidence of a causal relationship between periodontal disease and cardiovascular diseases: Position paper from the Canadian dental hygienists association. | Can J Dent Hyg 2020; 54:32-41.

- Legge A, Hanly JG. Managing premature atherosclerosis in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases. CMAJ 2018; 190:430-433.

- Sanz M, Marco Del Castillo A, et al. Periodontitis and cardiovascular diseases: Consensus report. J Clin Periodontol 2020; 47:268-288.

- Donley T. Time to put periodontal disease on the list of chronic inflammatory diseases contributing to premature atherosclerosis. CMAJ 2019; 191:e52.

- Demmer RT, Trinquart L, Zuk A, et al. The influence of anti-infective periodontal treatment on c-reactive protein: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS ONE 2013; 8:e77441.

- Önder C, Kurgan S, Altıngöz S, et al. Impact of non-surgical periodontal therapy on saliva and serum levels of markers of oxidative stress. Clin Oral Investig 2017; 21:1961-1969.

- Roca-Millan E, González-Navarro B, Sabater-Recolons MM, et al. Periodontal treatment on patients with cardiovascular disease: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2018; 23:681-690.

- Torumtay G, Kırzıoğlu F, Öztürk Tonguç M, et al. Effects of periodontal treatment on inflammation and oxidative stress markers in patients with metabolic syndrome. J Periodontal Res 2016; 51:489-498.

- Aljehani Y. Risk factors of periodontal disease: Review of the Literature. Int J Dent 2014; 2014:1-9.

- Arnett D. ACC/AHA guideline on the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease: A report of the American college of cardiology/american heart association task force on clinical practice guidelines. Circulation 2019; 140:e596–e646.

- Atchison K, Rozier R, Weintraub J. Integration of oral health and primary care: Communication, coordination, and referral. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper. National Academy of Medicine, Washington, DC 2018.

- Lang N, Bartold P. Periodontal health. J Periodontol 2018; 89:S9-S16.

- Caton G, Armitage G, Berglundh T, et al. A new classification scheme for periodontal and peri‐implant diseases and conditions–Introduction and key changes from the 1999 classification. J Clin Periodontol 2018; 45:S1-S8.

- Temelli B, YetkinZ, Savas HB, et al. Circulation levels of acute phase proteins pentraxin 3 and serum amyloid A in atherosclerosis have correlations with periodontal inflamed surface area. J Appl Oral Sci 2018; 26: e20170322.

- Bartold P, Van Dyke T. Host modulation: Controlling the inflammation to control the infection. Periodontol 2000; 2017:317-329.

- Blicher B, Joshipura K, Eke P. Validation of self-reported periodontal disease: A systematic review. J Dent Res 2005; 84:881-890.

- Hofer D, Sahrmann P, Attin T, et al. Comparison of marginal bleeding using a periodontal probe or an interdental brush as indicators of gingivitis. Int J Dent Hygiene 2011; 9:211–215.

- Albandar JM. Epidemiology and risk factors of periodontal diseases. Dent Clin North Am 2005; 49:517–532.

- Bale BF, Doneen AL, Vigerust DJ, et al. High-risk periodontal pathogens contribute to the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Postgrad Med J 2016; :1–6.

- Teshome, Yitayeh. The effect of periodontal therapy on glycemic control and fasting plasma glucose level in type 2 diabetic patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health 2017; 17:31

- Payne JB, Golub L, Thiele GM, et al. The link between periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis: A periodontist's perspective. Curr Oral Health Rep 2015; 2:20-29.

- Golub LM, Lee HM, Stoner JA, et al. Doxycycline effects on serum bone biomarkers in post-menopausal women. J Dent Res 2010; 89:644-649.

- Bansal M, Khatri M. Taneja potential role of periodontal infection in respiratory diseases-A review. J Med Life 2013; 6:244-248.

- Schmalz G, Wendorff H, Berisha L, et al. Association between the time after transplantation and different immunosuppressive medications with dental and periodontal treatment need in patients after solid organ transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis 2018; 20:e12832.

- Wahid A, Chaudhry S, Ehsan A, et al. Bidirectional relationship between chronic kidney disease and periodontal disease. Pak J Med Sci 2013; 29:211-215.

- Payão SLM, Rasmussen LT. Helicobacter pylori and its reservoirs: A correlation with the gastric infection. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther 2016; 7:126-132.

- Nascimento PC, Castro MML, Magno MB, et al. Association between periodontitis and cognitive impairment in adults: A systematic review. Front Neurol 2019; 10:323.

- Wahl MJ. Antibiotic prophylaxis in artificial joint patients. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2010; 68:949.

- Schwendicke F, Karimbux N, Allareddy V, et al. Periodontal treatment for preventing adverse pregnancy outcomes: A meta-and trial sequential analysis. PLoSONE 2015; 10:e0129060.

- Güven DC, Dizdar Ö, Akman AC, et al. Evaluation of cancer risk in patients with periodontal diseases. Turk J Med Sci 2019; 49.

- Nasseh K, Vujicic M, Glick M. The relationship between periodontal interventions and healthcare costs and utilization. Evidence from an Integrated dental, medical, and pharmacy commercial claims database. Health Economics 2017; 26:519-527.

- Trombelli L, Farina R, Silva CO, et al. Plaque‐induced gingivitis: Case definition and diagnostic considerations. J Clin Periodontol 2018; 45:S44–S67.

Author Info

Timothy G Donley1, Kristopher S Pfirman2*, Mohammed Kazimuddin2 and Aniruddha Singh2

1Bowling Green Institute for Periodontics and Implant Dentistry, Kentucky, United States2Department of Cardiology, The Medical Center-Bowling Green Western Kentucky Heart, Lung, and Gastroenterology, United States

Citation: Timothy G Donley, Kristopher S Pfirman, Mohammed Kazimuddin, Aniruddha Singh, Increasing Collaboration Between Dentistry and Medicine, J Res Med Dent Sci, 2020, 8 (6): 263-268.

Received: 12-Sep-2020 Accepted: 28-Sep-2020