Research - (2022) Volume 10, Issue 6

Matrix System Preferred for Class II Composite Restoration in University Setup

Kiran Kannan* and Deepak Selvam

*Correspondence: Kiran Kannan, Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences (SIMATS), Saveetha University, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India, Email:

Abstract

Aim & Background: One of the most common problems faced by dentists in restorative dentistry is the isolation and matrix system used in restoring class II composite restoration. Dental students commonly face the problem of overhanging proximal margins and unsatisfactory proximal contact points while restoring Class II cavities in posterior teeth. Various matrix band systems are used in dental clinics to avoid such problems and ease of the dentist. The aim of the study was to evaluate the prevalence of use of various types of matrix system preferred in Class II composite restoration in a university setup. Methodology: A cross sectional retrospective study of, with a study population of 1567 patients visiting Saveetha Dental College and Hospital who had been treated with Class II composite, the use of different types of matrix bands were noted. The data was tabulated in SPSS by IBM and was used for data analysis The Statistical test used was the Chi Square test. Results: The gender prevalence of patients included in the study, which shows that 1227 of them were male (53.6%) and 1061 of them were female (46.4%). The most common age group was 31 to below 20 years of age were 635 patients in the age group of (27.7%). The meso occlusal Class II caries was found to be 1164 of the total tooth (50.9%) which is most common of all. 721 of. The affected teeth were maxillary molars (31.5%). In 1681 cases sectional matrix system was used. Conclusion: From the conducted study we see that males were most commonly affected by class II caries. We also saw that the most common age group was below 20 years of age. Maxillary molars are the most common tooth to be affected by class II caries. Meso-Occlusal caries are common of class II caries. Sectional matrix is the standard matrix band used in the university setup. There is a need to increase the knowledge and uses of ivory retainer as it is easy to use and has a tight contact.

Keywords

Class II, Composite restoration, Matrix Band, Ivory, Sectional, Toffilmayer, Innovative technique

Introduction

In the year of 1908 G. V Blacks classified carious lesions of teeth according to the anatomical location of the lesion. If the lesion is extending towards the proximal surface of the molars or premolars it is considered as Class II caries. In order to restore the anatomical form, function, esthetics, comfort, and to preserve and positional stability of class II caries affected teeth it is essential to restore the teeth [1].

It is necessary to build up the anatomical proximal contact with the adjacent tooth to maintain the integrity of the dental arch against the masticatory forces, Composite resin restorations were introduced in dentistry in the 1960s [1,2]. Posterior resin composites are widely considered the first-choice material for posterior direct restorations. Their survival is good, since reviews have concluded that mean annual failure rates vary between 1% and 3%. Composite resins still force the clinician to deal with polymerization shrinkage, which can range from 2-3% for hybrids, micro fill and Nano filled composites. Many composite insertion techniques have been proposed in order to compensate chemical contraction, which usually incorporates an incremental placement of the composite resin such as: the three-site technique a horizontal layering the oblique technique or a segmental technique as described by Jackson which may include an initial bulk placement in 3 to 3.5 mm increments [3]. In spite of the various techniques some of the other problems faced with composite restoration are : post-operative sensitivity wear higher than tooth structure marginal leakage with recurrent caries and open contact areas [4]. A good proximal contact is important for a well-functioning dentition. When a proximal contact is too loose this may lead to food impaction, tooth migration, periodontal complications and carious lesions. When the contact is too tight this may result in tooth migration or trauma of the periodontal tissues when excessive force must be used to pass dental floss through the proximal contact [5].

Creating tight anatomic correct proximal contacts remains difficult when placing direct posterior composite restorations. This problem is based on several potential mechanisms, including that composite cannot be ‘condensed’ as can amalgam, which leads to an insufficient adaptation of the matrix towards the adjacent tooth, the polymerization shrinkage of the composite material and the effects on the tooth position due to the elastic behavior of the rubber dam [6].

Therefore, research has tried to overcome existing problems by improving material characteristics and application techniques. In this context, the choice of the matrix system and separation technique is an important factor [7]. In present dentistry, traditional circumferential matrix systems are used popularly, but show shortcomings regarding the creation of tight proximal contacts and their improper proximal matrix form [8].

Dr Joseph B.F. Tofflemire in 1946 introduced tofflemire retainer (Universal matrix system), was manufactured as a modified version of the Ivory No. 8 and 9 systems and is still in use today. The Tofflemire matrix retainer works in conjunction with various types of matrices: a universal, gingival extensions, and narrower gingival extensions matrix. The matrix retainer comes in 2 thicknesses (0.0020 and 0.0015 inches) and can accept straight and precontoured stainless steel bands. This matrix system can be used in many situations, but gained popular in class II amalgam and complex amalgam restorations. Though it is popularly used, but show shortcomings regarding the creation of tight proximal contacts and improper matrix forms [9].

Sectional matrix system is used as an alternative to circumferential bands since it was introduced in 1986. The sectional bands eliminated the “push-pull” problem faced with circumferential bands. Extra force supplied by separating rings, helps to produce more reliable contacts, even when there is significant space between teeth. However, there were several disadvantages to the original sectional matrix systems. They didn’t sit as tightly against the tooth as circumferential bands, leading to a greater chance of gingival overhang. The bands were shorter when compared to modern bands and harder to hold and manipulate. They could be difficult to position and stabilize. After wedge was introduced, they often shifted, opening margins, damaging tissue or tilting away from an ideal contact area and proximal form. The separating rings were not ideally shaped and the prongs often pushed the matrix band into the prepared space, or were not sufficiently retentive to stay in place [10].

This type of matrix band encircles the one proximal surface of the posterior teeth. It is attached to a retainer via a wedge-shaped projection. The adjusting screw at end the retainer adapts the band to the proximal contour of the prepared tooth. As the adjusting screw is rotated clockwise the wedge shape projection engage the tooth at the embrasures of the unprepared proximal surface [11].

Our team has extensive knowledge and research experience that has translate into high quality publications [12–31]. The aim of the study was to evaluate the prevalence of use of various types of matrix system preferred in Class II composite restoration in a university setup.

Materials and Methods

Study design

A prevalence study.

Study setting:

OPD Department in a private dental institution in Chennai.

Study size

2289 outpatients attending the OPD department.

Sampling and scheduling

Owing to the nature of the study design and setting, a convenience a sampling method was used, and the data was collected.

Survey instrument

An online platform called DIAS was used to collect the data and the data of patients undergoing trans alveolar extraction was tabulated and analysed.

Inclusion and Exclusion criteria

All those who underwent Class II composite restoration in Saveetha Dental College and Hospital were included in the study. Patients who restores with indirect Class II restoration or amalgam restorations were not included in the study.

Ethical clearance

Prior to the study, ethical clearance was obtained from the institution ethical committee of Saveetha University.

Statistical analysis

The collected data was tabulated in excel and were then imported to SPSS by IBM software, (version 25). Descriptive statistics were done using frequency and percentage.

Inferential statistics were done using the Chi-square test. Interpretation was based on a p value less than 0.05, which was considered statistically significant. Comparisons were done between independent variables like age, gender, occupation and knowledge, attitude, practice responses by the participants.

Results and Discussion

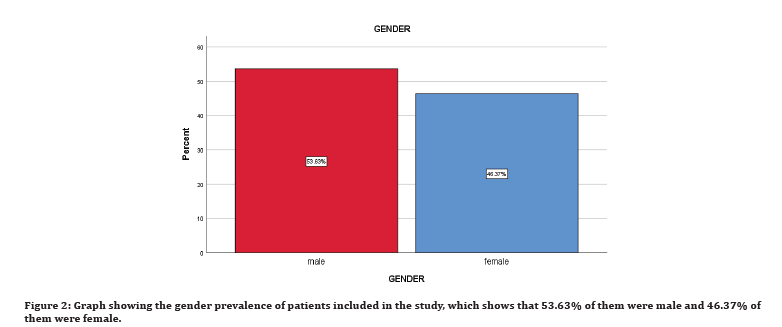

From the current study we see that most of the patients with class II restorations are males (56.63%), followed by females (43.37%) [32] reviewed a few studies reporting data about the gender gap regarding caries, and most researchers attribute this difference to the fact that, in general, permanent teeth erupt earlier in women than in men, this could be the reason for more prevalence of caries in men than in women.

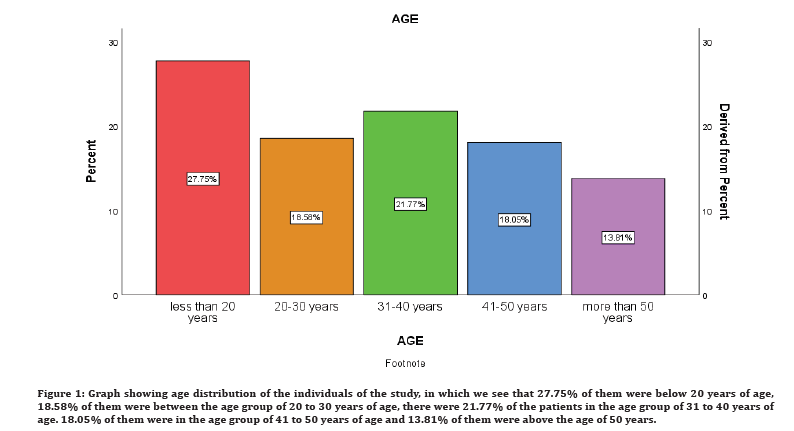

It was also observed that most of the patients were of the age group below 20 years (27.75%), followed by other age group- 31-40 years 21.77%, 21-30 years (18.58%), 41-50 years (18.05%), prevalence was seen least in the age group above 51 years with 13.81% [32,33]. In study it was concluded that caries were most common among individuals aged 17 to 25 years. These results are similar to that of the current study.

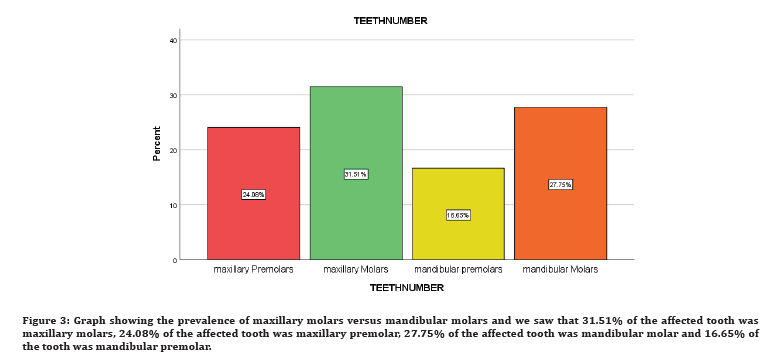

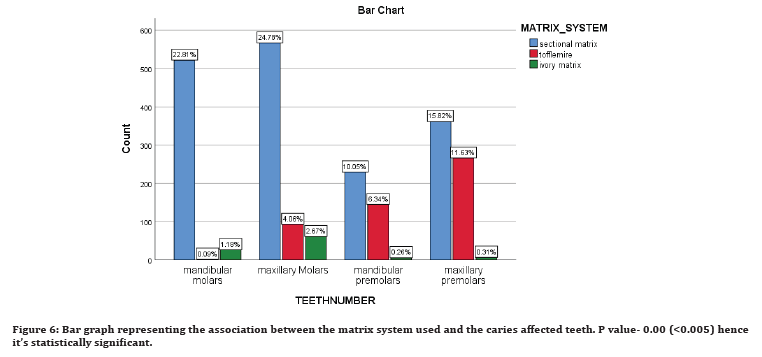

It was observed in the current study that 31.51% of the class II caries affected teeth were maxillary molars, followed by maxillary premolars with 24.08%, mandibular molars 27.75%, mandibular premolars 16.65%. This finding is similar to that of [34] in this prevalence study about class II caries, the results show that prevalence of caries are seen most in maxillary molars.

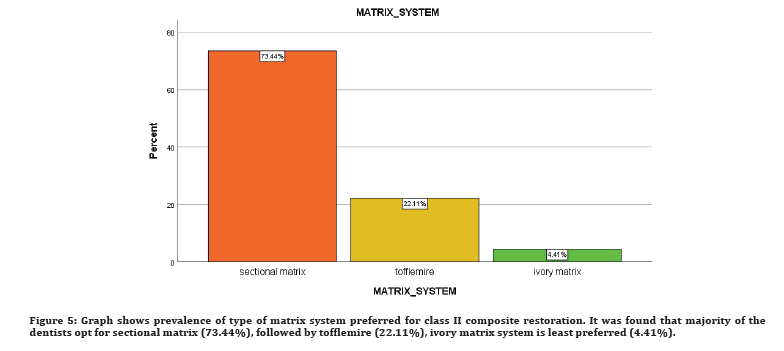

Current study reveals that the most commonly preferred matrix system in university setup is Sectional matrix, about 73.44% of the dentists prefer sectional matrix, followed by tofflemire (22.11%), and least preferred matrix system is ivory matrix (4.41%) [35]. recent study reveals that use of sectional matrix provided excellent results compared to that of tofflemire. Use of sectional matrix avoids overhangs and prevents the restoration from dislodging. Recent studies that compared the success rate of all the matrix systems concluded that Sectional metal matrix produced the highest proximal contact measurements, while tofflemire produced comparatively lesser measurements. Tofflemire metal matrix produced the same proximal contact measurements as conventional metal matrix [36].

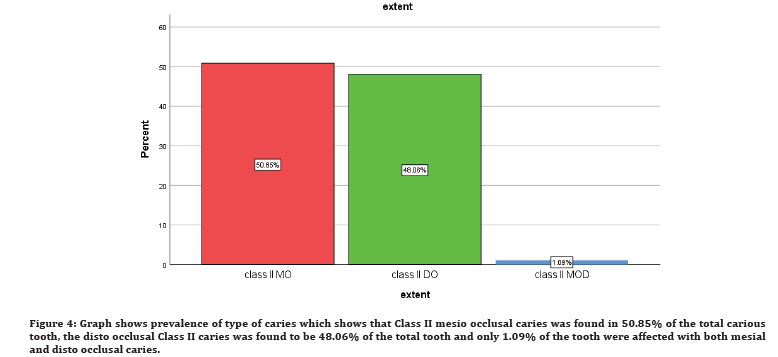

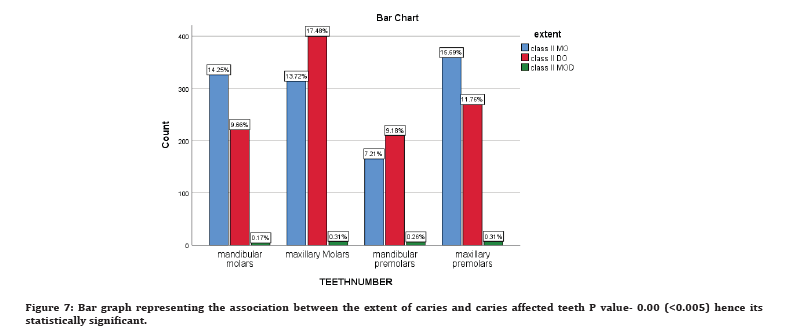

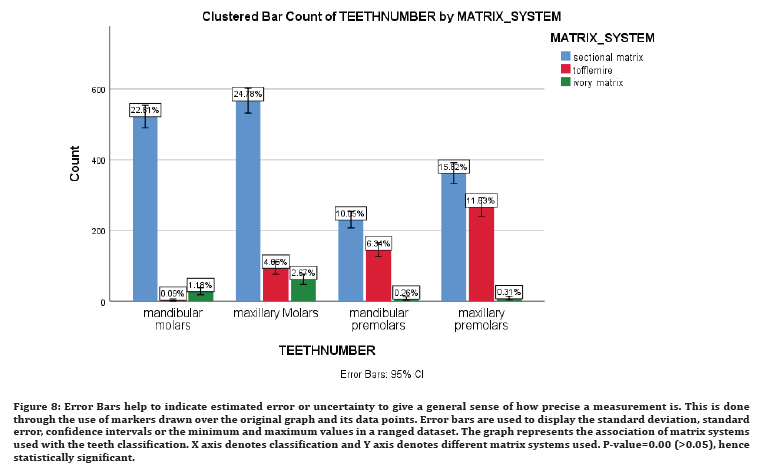

The prevalence of the extent of the caries were estimated in current study, it was found that class II caries with mesio occlusal caries (50.85%) was the most common, followed by class II with disto occlusal cries, least was seen in class II with Mesio-distal occlusal caries with 1.09% [37]. The association between tooth number that had class II caries and matrix system used for the restoration was observed. It was seen that the tooth number and matrix system has statistical significance with p value=0.00 (<0.005) hence it is statistically significant (Figures 1-8).

Figure 1: Graph showing age distribution of the individuals of the study, in which we see that 27.75% of them were below 20 years of age, 18.58% of them were between the age group of 20 to 30 years of age, there were 21.77% of the patients in the age group of 31 to 40 years of age. 18.05% of them were in the age group of 41 to 50 years of age and 13.81% of them were above the age of 50 years.

Figure 2:Graph showing the gender prevalence of patients included in the study, which shows that 53.63% of them were male and 46.37% of them were female.

Figure 3:Graph showing the prevalence of maxillary molars versus mandibular molars and we saw that 31.51% of the affected tooth was maxillary molars, 24.08% of the affected tooth was maxillary premolar, 27.75% of the affected tooth was mandibular molar and 16.65% of the tooth was mandibular premolar.

Figure 4:Graph shows prevalence of type of caries which shows that Class II mesio occlusal caries was found in 50.85% of the total carious tooth, the disto occlusal Class II caries was found to be 48.06% of the total tooth and only 1.09% of the tooth were affected with both mesial and disto occlusal caries.

Figure 5:Graph shows prevalence of type of matrix system preferred for class II composite restoration. It was found that majority of the dentists opt for sectional matrix (73.44%), followed by tofflemire (22.11%), ivory matrix system is least preferred (4.41%).

Figure 6:Bar graph representing the association between the matrix system used and the caries affected teeth. P value- 0.00 (<0.005) hence it’s statistically significant.

Figure 7:Bar graph representing the association between the extent of caries and caries affected teeth P value- 0.00 (<0.005) hence its statistically significant.

Figure 8:Error Bars help to indicate estimated error or uncertainty to give a general sense of how precise a measurement is. This is done through the use of markers drawn over the original graph and its data points. Error bars are used to display the standard deviation, standard error, confidence intervals or the minimum and maximum values in a ranged dataset. The graph represents the association of matrix systems used with the teeth classification. X axis denotes classification and Y axis denotes different matrix systems used. P-value=0.00 (>0.05), hence statistically significant.

It was also observed in the study that there was significant association found between tooth number and extent of class II caries. P value was found to be 0.00 (<0.05), hence statistically significant. The limitations of the study are that limited sample size, further studies should focus on increasing the sample size, including other ethnic groups.

Conclusion

Within the limitations of the study we are able to conclude that males had more prevalence of class II than females. We also see that class II caries is more common among the age group less than 20 years, most commonly affected teeth were maxillary molars. The most commonly preferred matrix system in the university setup is sectional matrix. There was statistical significance found between tooth number and matrix system preferred for class II restoration. It was also found that there is statistically significant found between tooth number and extent of caries.

Acknowledgement

Current study is supported and funded by Saveetha institute of medical and technical science.

Conflict of Interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Source of Funding

The present project is supported by

Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Science, Saveetha University, India

4 U Parma has funded this project.

References

- Jackson RD. Class II composite resin restorations: Faster, easier, predictable. Br Dent J 2016; 221:623–631.

- Christensen GJ. Making Class II resin-based composite restorations predictable and profitable. J Am Dent Assoc 2010; 141:457-460.

- Fissore B, Nicholls JI, Yuodelis RA. Load fatigue of teeth restored by a dent in bonding agent and a posterior composite resin. J Prost Dent 1991; 65:80–85.

- Chestnutt IG, Schafer F, Jacobson AP, et al. Incremental susceptibility of individual tooth surfaces to dental caries in Scottish adolescents. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1996; 24:11–16.

- Machin D, Day S, Green S. Textbook of clinical trials. John Wiley & Sons 2007; 784.

- Eakle WS. Fracture resistance of teeth restored with class II bonded composite resin. J Dent Res 1986; 65:149–153.

- Dietschi D, Spreafico R. Adhesive Metal-free restorations: Current concepts for the esthetic treatment of posterior teeth. Elsevier 1997; 215.

- Hujoel PP, Lamont RJ, DeRouen TA, et al. Within-subject coronal caries distribution patterns: An evaluation of randomness with respect to the midline. J Dent Res 1994; 73:1575–1580.

- Durr-E-Sadaf, Ahmad MZ, Gaikwad RN, et al. Comparison of two different matrix band systems in restoring two surface cavities in posterior teeth done by senior undergraduate students at Qassim University, Saudi Arabia: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Indian J Dent Res 2018; 29:459–464.

- Gupta R, Hegde J, Prakash V, et al. Concise conservative dentistry and endodontics-E Book. Elsevier Health Sciences 2019; 500.

- Arhun N, Cehreli SB. Do adhesive systems leave resin coats on the surfaces of the metal matrix bands? An adhesive remnant characterization. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent 2013; 33:e43–50.

- Muthukrishnan L. Imminent antimicrobial bioink deploying cellulose, alginate, EPS and synthetic polymers for 3D bioprinting of tissue constructs. Carbohydr Polym 2021; 260:117774.

- PradeepKumar AR, Shemesh H, Nivedhitha MS, et al. Diagnosis of vertical root fractures by cone-beam computed tomography in root-filled teeth with confirmation by direct visualization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endod 2021; 47:1198–1214.

- Chakraborty T, Jamal RF, Battineni G, et al. A review of prolonged post-COVID-19 symptoms and their implications on dental management. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18.

- Muthukrishnan L. Nanotechnology for cleaner leather production: A review. Environ Chem Lett 2021; 19:2527–2549.

- Teja KV, Ramesh S. Is a filled lateral canal: A sign of superiority? J Dent Sci 2020; 15:562.

- Narendran K. Synthesis, characterization, free radical scavenging and cytotoxic activities of phenylvilangin, a substituted dimer of embelin. Indian J Pharm Sci 2020; 82:909-912.

- Reddy P, Krithikadatta J, Srinivasan V, et al. Dental caries profile and associated risk factors among adolescent school children in an Urban South-Indian City. Oral Health Prev Dent 2020; 18:379–386.

- Sawant K, Pawar AM, Banga KS, et al. Dentinal microcracks after root canal instrumentation using instruments manufactured with different NiTi alloys and the SAF system: A systematic review. NATO Adv Sci Inst Ser E Appl Sci 2021; 11:4984.

- Bhavikatti SK, Karobari MI, Zainuddin SLA, et al. Investigating the antioxidant and cytocompatibility of mimusops elengi linn extract over human gingival fibroblast cells. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18.

- Karobari MI, Basheer SN, Sayed FR, et al. An in vitro stereomicroscopic evaluation of bioactivity between neo MTA Plus, pro root MTA, biodentine & glass ionomer cement using dye penetration method. Materials 2021; 14.

- Rohit Singh T, Ezhilarasan D. Ethanolic Extract of Lagerstroemia speciosa (L.) pers., induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in HepG2 Cells. Nutr Cancer 2020; 72:146–56.

- Ezhilarasan D. MicroRNA interplay between hepatic stellate cell quiescence and activation. Eur J Pharmacol 2020; 885:173507.

- Romera A, Peredpaya S, Shparyk Y, et al. Bevacizumab biosimilar BEVZ92 versus reference bevacizumab in combination with FOLFOX or FOLFIRI as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 3:845–55.

- Raj R K. β‐Sitosterol‐assisted silver nanoparticles activates Nrf2 and triggers mitochondrial apoptosis via oxidative stress in human hepatocellular cancer cell line. J Biomed Material Res 2020; 108:1899.

- VijayashreePriyadharsini J. In silico validation of the non-antibiotic drugs acetaminophen and ibuprofen as antibacterial agents against red complex pathogens. J Periodontol 2019; 90:1441–1448.

- Priyadharsini JV, Vijayashree Priyadharsini J, Smiline Girija AS, et al. In silico analysis of virulence genes in an emerging dental pathogen A. baumannii and related species. Arch Oral Biol 2018; 94:93–98.

- Uma Maheswari TN, Nivedhitha MS, Ramani P. Expression profile of salivary micro RNA-21 and 31 in oral potentially malignant disorders. Braz Oral Res 2020; 34:e002.

- Gudipaneni RK, Alam MK, Patil SR, et al. Measurement of the maximum occlusal bite force and its relation to the caries spectrum of first permanent molars in early permanent dentition. J ClinPediatr Dent 2020; 44:423–428.

- Chaturvedula BB, Muthukrishnan A, Bhuvaraghan A, et al. Dens invaginatus: A review and orthodontic implications. Br Dent J 2021; 230:345–350.

- Kanniah P, Radhamani J, Chelliah P, et al. Green synthesis of multifaceted silver nanoparticles using the flower extract of Aervalanata and evaluation of its biological and environmental applications. Chemistry Select 2020; 5:2322–2331.

- Brislin JF, Cox GJ. Survey of the Literature of Dental Caries, 1948-1960. 1964. 762 p.

- Demirci M, Tuncer S, Yuceokur AA. Prevalence of caries on individual tooth surfaces and its distribution by age and gender in university clinic patients. Eur J Dent 2010; 4:270–279.

- Anusavice K. Clinical decision-making for coronal caries management in the permanent dentition. J Dent Educ 2001; 65:1143.

- Saber MH, Loomans AC, El Zohairy A, et al. Evaluation of proximal contact tightness of class ii resin composite restorations. Operative Dent 2010; 35:37–43.

- Wirsching E, Loomans BAC, Klaiber B, et al. Influence of matrix systems on proximal contact tightness of 2- and 3-surface posterior composite restorations in vivo. J Dent 2011; 39:386–390.

- Loomans BAC, Opdam NJM, Roeters FJM, et al. Comparison of proximal contacts of Class II resin composite restorations in vitro. Oper Dent 2006; 31:688–693.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Author Info

Kiran Kannan* and Deepak Selvam

Department of Conservative Dentistry and Endodontics, Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences (SIMATS), Saveetha University, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, IndiaCitation: Kiran Kannan, Deepak Selvam, Matrix System Preferred for Class II Composite Restoration in University Setup, J Res Med Dent Sci, 2022, 10 (6):154-160

Received: 26-May-2022, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-65015; , Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-65015 (PQ); Editor assigned: 28-May-2022, Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-65015 (PQ); Reviewed: 14-Jun-2022, QC No. JRMDS-22-65015; Revised: 17-Jun-2022, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-65015 (R); Published: 24-Jun-2022