Research - (2022) Volume 10, Issue 11

MENSTRUAL HYGIENE HABITS AND WASTE DISPOSAL PRACTICE AND CHALLENGES FACED BY WOMEN IN SALEM DISTRICT FROM 1947 TO 2000

*Correspondence: Gejalakshmi M, Department of History, Thiruvalluvar Government Arts College, Rasipuram, India, Email:

Abstract

There are still many social, religious and cultural barriers that women face when it comes to menstrual period and the practices that accompany it, making it difficult to maintain good menstrual hygiene. It remains one of the best most challenging issues and challenges to deal with today in terms of menstrual hygiene (MH). Personal choices, economic factors and norms all played a role in how women handled their MH. Menstrual management practices are lacking in most states, so women tend to flush their sanitary napkins and other menstrual products down the toilet or toss them in the trash, where they end up as part of the overall waste stream. A course on menstrual period and menstrual hygiene management should be done to raise awareness of menstrual hygiene. Many women face difficulties at home, school, and work because they are unprepared and largely ignorant of menstruation in many parts of the country, especially in rural areas. Numerous nations around the globe still don't have a system in place for properly disposing of used menstrual materials. Paper discusses the importance of women's MH habits and disposal practices and the difficulties they face Belief systems about menstrual period and women's sewage treatment are also examined in this survey. This paper also discusses the benefits of consciousness concerning periods and menstrual devastate managing. This survey aims to MH practice and waste removal practices and challenge face by women in the Salem district from 1947 to 2000.

Keywords

Menstruation, Menstrual hygiene, Menstrual health, Waste disposal management, Challenges faced by women

Introduction

A girl child aged 11–18 years is classified as an adolescent by the “World Health Organization”. Puberty is the stage of transition among youth and maturity, because the child grows, this is distinct. The morphological, behavioral, and hormonal development of a kid occurs throughout this period. Girlhood is recognized as a particular time that calls for extra care. A female's menarche marks the beginning of her fertile age, making it a powerful hormonal milestone. The typical time for “menarche” is among the ages of 12 and 13, which is very stable among populations. However, the situation for females worsens down to a lack of awareness about menstrual preparation and control, as well as nervousness and discomfort [1].

From adolescence (ages 10–23) and menopausal (ages 46–56), a woman goes through 458 cycles of menstruation. The usage of sanitary napkins is quickly expanding through fast civilization, growing affluence, greater invention offerings, delivery and immovability. Due to poor hygiene, communal and public infrastructure upkeep is frequently a source of environmental health concerns. Deprived squander removal on-site cause worry and tension in nations wherever menstrual is stigmatized and tabooed. This concern about ability maintenance, together with the truth that so many shortand middle class nations have issues with urban trash collection, produces exposure dangers and pollution in densely populated areas [2].

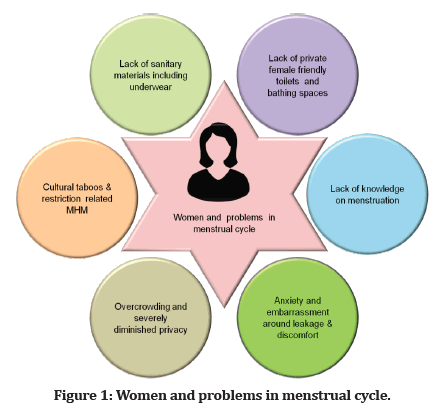

Disposable napkins (cloth torn with women's costumes and cotton fabric) to available commercially sanitary napkin pads are used as adsorbents during periods in low-income nations like India. For convention the MH wants of women in less income countries, sustainable, acceptable approaches are used. Genitourinary tract infections, social isolation, anemia, and school absenteeism are all linked to the adsorbents used, hygiene procedures, and social limitations that women face during periods [3]. Figure 1 depicts the women and problems in menstrual cycle.

Figure 1: Women and problems in menstrual cycle.

The MHM in Ten goals and objectives have been integrated into the planning of various institutes, and the call to arms has been quoted over 109 times. The action case is growing globally, and a small number of subnational level menstrual regulations have been implemented. 5 years have gone by since the agenda was launched, necessitating a review of whether and how progress is made halfway between the development of objectives and the ten-year deadline [4].

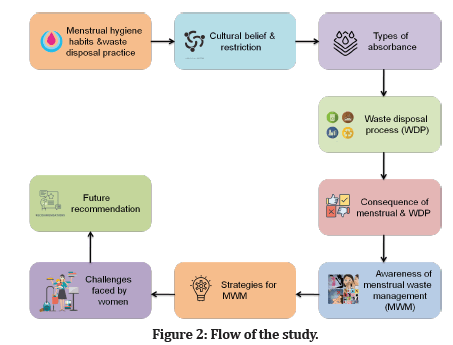

According to a comprehensive examination of Indian studies, only half of the teenage girls in India are knowledgeable about menarche until their initial menstrual and have insufficient information when they reach menarche-stage. It as well stated that the scarcity of secure and sanitary menstrual waste disposal solutions was concerning. The Indian government attaches great importance to MH to the wellbeing, comfort, and instructive achievement of women and girls and MHM in schools is being improved through a number of projects supported by various groups, which include raising the awareness of menstruation debris and accessibility to menstruation products, as well as improving sanitary conditions in schools. Just a few instances are low-cost menstrual napkins in rural regions, school vending machines for sanitary napkins and pads incinerators, as well as the extension of gender-segregated restroom facilities [5]. Figure 2 depicts the study's progression as a whole.

Figure 2: Flow of the study.

The importance of MH habits and devastates removal practice and challenge face by women is discussed in this paper. The cultural belief and restrictions during menstruation and the waste disposal process used by women are also addressed in this survey. This report also emphasizes the advantages of periodic hygiene and waste disposal knowledge. From 1947 through 2000, this study looked at women's menstrual hygiene routines, waste disposal techniques, and issues in the Salem region.

Menstrual hygiene habits and waste disposal practice

People who live near riverbeds pour period waste into waterways, contaminating them. Pathogens and dangerous microorganisms thrived in these substances that had been badly burnt. Sanitary goods soaking in the blood of an affected female may carry influenza and HIV viruses, which can survive in the ground for up to 6 months and keep their viral load. Lacking suitable safety or gear, the blocked sewers containing napkins must be manually cleared and cleansed by conservation employees with their bare hands. Workers are exposed to dangerous chemicals and microorganisms as a result of this. Although burning is a healthier method of disposing of menstruation waste, burned pads emit toxic gases that are damaging to both health and wellbeing. When inorganic materials are burned at low temperatures, dioxins are released, which are poisonous and cancerous in origin [6].

The waste disposal tactics exacerbated the society's current waste problems; girls and instructors stated that menstruation waste deposited in ditches and drainage of school toilets regularly created issues with toilet function and encouraging pests. Girls just at vocational school were told to “secret agent upon at the restrooms” in order to find out if only they had “mucked up the restrooms,” to “document on girls getting rid of pads in the public,” and to penalize them by arranging wash campaign groups of unhygienic sites - however without finding alternative sanitary landfill remedies. Teachers appeared to accept trash being dumped on the edges of the school grounds because they saw no other options [7].

Cultural belief and restriction

Regional conventions, parent involvement, personal choices, economic standing, and social conditioning all influenced menstrual hygiene (MH) behaviors. Periodic myths refer to cultural or religious myths and views about menstrual. Menstrual hygiene management (MHM) was intertwined with menstruation beliefs, understanding, and actions. Many researchers discovered several cultural and religious ideas about menstruation by researching material; publications published papers, and data available on the Web. Great MH procedures were thwarted by these rules. Most women have restrictions on their daily activities, including preparing meals, household chores, sexual activity, personal hygiene, spiritual practices, and even the items they can eat. Menstruation was considered nasty and dirty by the general people, thus these restrictions were put in place to protect them [8].

Women in India would avoid showering during their periods. In terms of dietary restrictions during menstruation, studies have found that spicy foods, pickles, fruits, and vegetables are prohibited during menstruation, and spicy foods, fruits, and vegetables are prohibited in girls and women during menstruation. In addition, some studies were discovered in which some women not only did not mention a restriction in eating during menstruation but also mentioned eating things like fruits and vegetables to compensate for the blood they had lost, and there were studies in which the consumption of fruits, vegetables, fiber, and adequate vitamin D and calcium resources such as dairy were emphasized in the reduction of dysmenorrheal.

In terms of belief in the effects of specific methods in menstruation, such as pain relief, blood reduction, the use of specific pads, and restricting exercise and activity, similar studies have found that in many cultures, including the one studied here, belief in the treatment of menstruation symptoms with herbal remedies, local heating, back massage, and fluid consumption exists. The relative appropriateness of sanitary pads, as well as access to different types of sanitary pads and bundled clothes in city drugstores and sales centers, led to simple access to diverse types in the population studied. Similar studies offer varied outcomes when it comes to participants' perception of the importance of limiting activity and exercise during menstruation [9].

While some women in some studies believed that exercise and physical activities were harmful during this time, and some girls did not even do housekeeping during this time, similar studies conducted in the form of clinical activity indicated that in many cultures, including the one studied here, belief in the treatment of menstruation symptoms with herbal remedies, local heating, back massage, and fluid therapy was common. It has been demonstrated that frequent exercise, Helps in the reduction of stress in women's blood circulation improvement, increases neurotransmitters and endorphins, and the demographic being studier’s views that exercise causes blood pressure to rise. Better blood circulation may be to blame for the discharge, due to circulation in the uterus and surrounding the pelvis to work out. Many different cultures have menstrual blood was regarded as disgusting and consider menstruation to be nasty and unclean as well as irregular monthly blood flow. The origin of this was traced to different cultures and faith in religious beliefs [10].

Types of absorbance

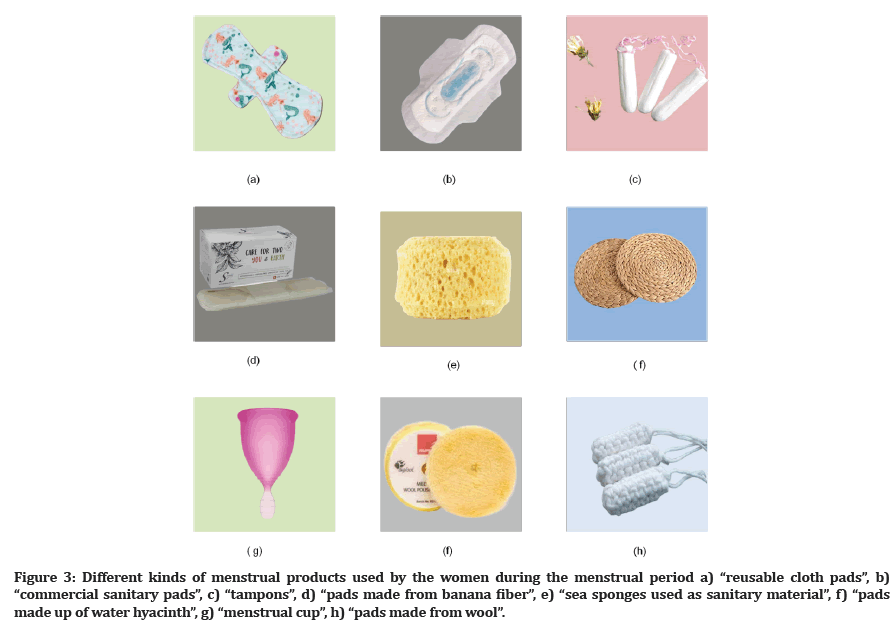

Personal choice, cultural tolerance, financial status, and traditional market accessibility all influence sanitary protective substance selection. To regulate period cleanliness, along with basic sanitary facilities, detergent and menstrual wetting agents should be given. Various materials are used by ladies in rural and urban regions. Disposable pads are preferred by women in rural regions whereas sanitary napkin pads are preferred by those in metropolitan centers. Fluffy pulp for sanitary napkins items is made from chlorine Fiber or sulphates pulp by producers. Many rayon-based hygiene solutions, both deodorized and semi are presently on the marketplace. Inorganic chlorine insecticides, for example, are antifungal substances found in these properly sanitized products. Based on their chemical composition, these substances harm local soil microbes and limit their decomposition in the soil [11]. Figure 3 represent the different kinds of menstrual product used by women during menstrual period.

Figure 3: Different kinds of menstrual products used by the women during the menstrual period a) “reusable cloth pads”, b) “commercial sanitary pads”, c) “tampons”, d) “pads made from banana fiber”, e) “sea sponges used as sanitary material”, f) “pads made up of water hyacinth”, g) “menstrual cup”, h) “pads made from wool”.

Reusable and washable cloth pads

They should be cleansed in the sun because they are lengthy hygienic options. Reusable cloth/cloth padding is disinfected by the intense light. In addition to being cheap and convenient, these reusable pads are also ecologically friendly. They should be stored in a safe, dry place in order to prevent the spread of disease.

Commercial sanitary pads

Retailers, clinics, and the internet all sell them. In addition to costing more than textile napkins, these disposable pads can't be washed or aren't beneficial for the earth. They aren't all-natural, and the cloth used to produce them may contain some chemicals [12].

Tampons

This type of absorption provides inner safety. The endometrial blood collected using these little cotton buds, which are inserted into the vaginal opening. Not only are they expensive, but they're also tough to decay in nature, making them unsustainable. Tampons made from sea sponges, environmentally friendly alternatives to synthetic ones, are now readily accessible in stores.

Reusable tampons

Wool, cotton, bamboo and hemp are all examples of organic substances that may be recycled into new hygienic goods over and over again. Knitted from pure absorb fabrics like cotton, they are also hypoallergenic and hypoallergenic. Tampons-like devices collect period fluid by being put in women's genital canals.

Menstrual cups

A contemporary technique for disadvantaged females, they could be an alternative to hygienic tampons and pads. Menstrual bleeding may be absorbed using these silicone adhesive cups, which look like cups but are constructed of healthcare rubber and can be inserted into genital opening. It is possible to wear them for up to 11 hrs, depending on the amount of menstrual blood that is present, making removing and emptying more common. They can be washed and are environmentally beneficial at the same time. In the long run, it's a lengthy, realistic, and pricey answer [13].

Bamboo fibre pads

Rather than wood pulp, these disposable sanitary products use bamboo pulp as an absorber. It has a larger absorbency, safe to use. These antifungal pads are lowcost, readily degradable, and kind to the ecosystem. As a result, menstrual cramps and pain are prevented. The benefit of using activated charcoal pads is that they don't display brown stains and can be cleaned.

Banana fibre pads

Slashed banana peels have been used to achieve lower menstruation pads in India under name “Saathi”. They are pollution free and will decompose in six months. In rural places, ladies also utilize animal manure, grasses, and mud as well as these goods.

Water hyacinth pads

Menstrual pads manufactured from water species are sold under the “Jani” branding. They're limited, recyclable, and safe for the planet [14].

Waste Disposal Process (WDP)

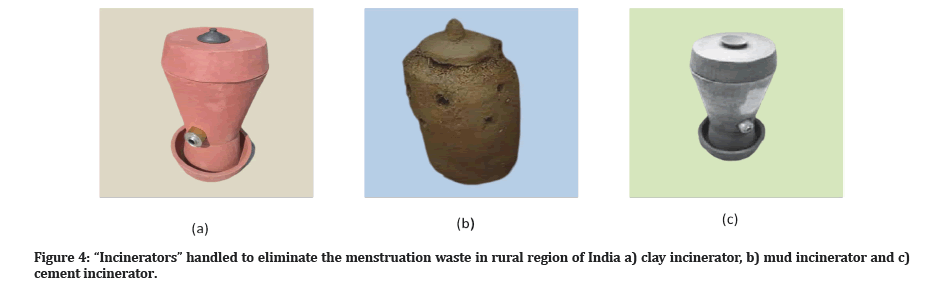

In several countries around the world, properly disposing of old menstrual substance is at rest insufficient. Most nations include made processes for managing their feces and urine waste, but outstanding to a need of menstrual managing activities, most women discard their hygienic pad or additional menses publications in household solid waste or trash bins, which eventually are becoming part of waste material [15]. Figure 4 depicts the incinerators handled to eliminate the menstruation waste in rural region of India.

Figure 4:“Incinerators” handled to eliminate the menstruation waste in rural region of India a) clay incinerator, b) mud incinerator and c) cement incinerator.

In our country, restrooms devoid of hygienic padding dumping bin and essential sanitation for menstrual women to manage MH. In city areas wherever contemporary not reusable menses product lines are use, they are disposed of by emptying in restrooms, menstruation material can be disposed of in a variety of ways, include dumping, going to burn, tossing in the trash, or to use sanitation facilities in rural regions without access to solid waste treatment. Most women in countryside regions utilize reusable and noncommercial sanitary products such as washable pads or cloths. Thus, they produce less menstruation-related trash compared to women who use commercialized throwaway pad in metropolitan settings. Menstrual waste was disposed of according to the core tradition, the location where it was rid of, and the type of goods utilized. Because burning and burial were impossible due to a lack of personal area in housing regions, women disposed of their menstruation waste in pit latrines. It was observed by males or employed in witch for this purpose [16].

Consequence of Menstrual and Wdp

Because sanitary facilities are built to handle human waste, they cannot handle menstruation absorbent substances. These absorption materials choke sewer systems since they can't pass through them, causing leakage. Excluding the plastic inlay of commercialized sanitary napkins, items like tissues, cotton balls, toilet tissue, and other organic products used for period control may disintegrate in sanitation facilities. Except for the plastic liner in on-site cleaning, disposable diapers may degrade in about a year. Pit latrines in rural regions were filled with earth and a fresh pit was created once they were full, but this was not done in urban areas due to space constraints. Some women and girls have been reported to enfold their used menstruation cloth and packages in polythene prior to discarding them in hollow latrines, preventing decomposition [17]. Figure 5 shows the vending machine for sanitary napkins.

Figure 5:Vending machine for sanitary napkin.

Currently, most women and girls choose sanitary napkin sanitary pads composed of ultra-absorbent polyacrylate polymers. A massive health risk is created by the expansion of these absorbent products when drained, since they suck up fluids and cause sewage flow. The porous polymer sheets and sticky wings of hygiene products make them difficult to degrade. The substantial trash or sand that accumulates in the pits leads the sludge to harden, resulting in drainage clogs. The flushing of menstruation products in toilets is a major contributor to sewage system blockage, which is a worldwide issue. Lightly scented feminine hygiene products include bleaching agents such as organ chlorines, which disrupt soil microflora and require time to decompose when deposited in the ground [18].

Awareness of menstrual waste management

Teachers to help girls and women handle periods with respect by making the school atmosphere girl/ woman sociable. Sexual education assists adolescents in determining their gender orientation, protecting themselves from sexual assault, unplanned children, and sexually transmitted infections, as well as understanding biological effects on the body and how to keep proper cleanliness. In most situations, instructors' attitudes toward menstruation girls in schools are not positive or encouraging. Families, educators, and communities all have multiple viewpoints on sexual education and universities. Cultural, religious, and social differences can obstruct progress in sexual education [19].

When children are able to focus on the transitions and problems that they face in their everyday lives, our instructional system would help them grow. However, it frequently avoids discussing topics connected to menstruation and MHM because to discuss it outside the house is deemed a breach of privacy. Menstrual period is a hidden issue for many women, and it is impacted by a variety of factors, including the teacher's attitude, the atmosphere of the school, and the physical facilities. As a result, many female students miss educate through this time. Sexual teaching is frequently absent out of educate curriculum, which has severe effects on learners' life. They obtain knowledge on adolescence, sexual activity, menstrual, and other physiological physical changes from textbooks, colleagues, and the Online, which may be inadequate or incorrect. Due to a shortage of knowledge and social interaction in the classroom, students frequently use unpleasant surnames as a means of mocking and teasing. A girl frequently misses class due to her inability to cope in such an environment [20].

Strategies for menstrual waste management

WDP is a big topic since it has an impact on both health and the environment. Effective menstruation materials that require less and expense maintenance are needed. Companies producing hygienic pad or additional goods must unveil the chemical structure of the pad so that suitable solutions for disposal methods can be applied. Producers of hygiene goods should employ environmentally friendly ingredients to prevent water and soil pollution and speed up the degradation rate. Menstrual management education for adolescent women and girls portent step is needed. MHM is included in all educational programs. Menstruation goods must be freely distributed at schools and colleges. Instead of supporting menstrual pads, the Indian government immediately placed a 12 percent GST on them, which is unwelcoming to women.

The needs of ladies should be taken into consideration while designing restrooms. Coin-operated sanitary disposal devices have been installed at different schools in Kerala. In case of emergencies, it comes with 20-60 hygiene products. Menstrual wastes should be collected separately from other wastes, preserving women's privacy and dignity. Menstrual waste should be collected using specific sanitary dispensers. Washing, cleansing private bits and hands, and changing or coping with raggedy clothes should all be possible. Waters, toilet tissue, a trashcan, and a basin to clean menstruation items are all required to meet these needs. To maintain the restrooms free of flies, insects, & poor odor, rubbish bins must be closed with a top and removed regularly. Covering bins and dustbins provide the profit of conceal the garbage starting sight. They are located in a position that act as a shield. To protect cleaners from microbial pathogens and dangerous fumes, masks, and suitable protective gear should be given [21].

The government has enacted new guidelines for the proper disposal methods of menstruation wastes, similar to those already in place for solid or biological wastes. MHM requires a proper legal and legislative environment. Governmental and semi organizations must work together to raise public awareness about MWM. The government must provide cash to the Municipality or non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to build women-friendly bathrooms. Menstrual pollutants should be thoroughly researched for their health effects. Organizations should be granted financial assistance to do studies on the disposal of menstruation wastes. Scientific research into the best methods for disposing of sanitary pads and other menstruation products should be promoted. Budgets should be set aside in schools to promote studies on menstrual hygiene management. Trash containers should be used in collaboration. Incinerators are a superior disposal solution, but they must be operated in a controlled atmosphere to avoid dangerous gas emissions harming a greater region [22].

Challenges faced by women

Access to effective and accurate knowledge is a necessity for maintaining sanitary menstruation practices. Menstruation is a natural biological event that is poorly understood in various social groups, according to studies conducted across the country. There are cultural practices, sentiments, and actions that make it difficult for women to talk openly about menstruating. As a result, not only are ladies ashamed to bring up the matter, but so are school instructors and even medical professionals. To modify the long-standing social attitude regarding menstruating and to overcome the culture of silence and indifference, all-out efforts are required. For teenagers' healthy growth, puberty education must integrate MHM on a curricular level. It is more impactful to educate both boys and girls about the physiological and behavioral parts of maturation, menstrual cycles, and MHM, rather than simply focusing on the practical issues of trying to manage menstrual, such as the use of products and building the capacity of educators and health providers. To a larger extent, eradicating gender-based discrimination will be easier if males in the community are educated about the issue and encouraged to adopt a supporting attitude. In addition, a comprehensive review of the current awareness training aimed at changing community norms surrounding menstruation will help identify critical gaps which must be filled in the future if MHM consciousness is to grow in a responsible way [23]. Figure 6 represents the challenges faced by women.

Figure 6:Challenges faced by the women.

The establishment of a social safety net will also benefit from the engagement of key social traditions, like social and religious organizations, in the fight against negative attitudes and misunderstandings. Making people aware of MHM's importance will be challenging unless we can improve on existing, active listening.

Future recommendation

The removal of old adsorbent materials requires consumer creative thinking that takes into account cultural norms around bleeding, product offerings, quality, and use, as well as room cleaning infrastructure. Female’s health, the wellbeing of cleaning crew, and the ecological impact of menstrual waste must all be taken into consideration when deciding how to dispose of menstruation material at an institutions or in a community setting. Health and environmental health research have proven that trash objects thrown of in the public or processed by rubbish or cleaning workers constitute a risk of transmission of infection. Period items, including disposables, compostable, and reusable’s, need to be studied for the health effects of chemicals and hygienic usage. Waste management practices, such as combusting different kinds of sanitary napkins, should be studied for their health impacts. Thermo chemical methods and technologies, including incinerator types, repair and commissioning, inlet temperature, and incinerator emissions, require further research and study. There should be a focus on educating girls and women about the many menstrual hygiene items offered and the sanitary implications of their usage, as well as educating them on the benefits and drawbacks associated with each. Innovative yet easy behavioral interventions that encourage correct waste disposal should be identified, tested, and scaled up. An emphasis is placed on waste management systems, notably incinerator technology across a range of contexts, with operators and institutions receiving enough training to guarantee the seamless operation of these technologies. The MWM process, from proper waste and management to waste collection, transport, and ultimate treatment and disposal, should be wellarticulated and operationally managed. Implementing research and clinical monitoring indicators will center on menstruation waste management systems and technologies [24].

All MHM initiatives, particularly waste minimization, must meet and recognize the specific MH requirements of ladies who are less competent or in risky positions (such as catastrophes). The MH product sector, administration, and quasi organizations will work together to build worldwide conferences for bridge and understanding on the increasing products environment and trash security solutions. There should be clear information on how public bodies can work together to help with detailed MHM programmers so that MHM is seen as a priority issue by all departments involved in solving it in different ways (through learning, wellness, hygiene, women having and empowering justice) [25].

Conclusion

An education on menstruation and MHM should be implemented to promote menstrual hygiene. Educators must be trained and qualified to provide students with information on menstruation and MHM. Through social media technologies, women are kept up to aware of the latest products, alternatives producers, and legislation. Every child and woman should be able to afford menstrual supplies through government aid. There is a pressing need for non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to take the lead in educating rural populations about the need of home bathrooms, hand-washing, genital tract infections caused by poor hygiene, and so on. Biodegradable sanitary or cotton pads are used to prevent the issue of disposal. Women should be aware of the hazards of dumping outdated menstrual products down the toilet. The restrooms should be equipped with trash cans with appropriate covers. Facilities should be located in homes, institutions, and communities whenever possible. As per results of this study, many people are concerned about their right to privacy at home and at school. Confusion, misconceptions, harmful practices, and knowledge concerning menstrual are all factors that contribute to a wide range of problems for both mothers and their children. As a result, teaching teens to behave in a healthy and hygienic manner in the education is a top priority. The discharge of old absorbent materials requires consumer design thinking that takes into account socio-cultural conventions around bleeding, product offerings, performance, and use, as well as accessible hygiene infrastructure. When it comes to sanitary and effluents control systems, menstrual waste must be taken into consideration and integrated into both the pollution and hygiene frameworks of a WASH curriculum, as well as solutions that reduce the adverse effects on women, garbage collectors, and widening environmental implications. This is especially important in society settings. Wastage and disease eradication with thermal properties may be a viable option in many instances and be accepted by the public if done correctly.

References

- Kaur R, Kaur K, Kaur R. Menstrual hygiene, management, and waste disposal: practices and challenges faced by girls/women of developing countries. J Environ Public Health 2018; 2018.

- Elledge MF, Muralidharan A, Parker A, et al. Menstrual hygiene management and waste disposal in low and middle income countries: A review of the literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018; 15:2562.

- Budhathoki SS, Bhattachan M, Castro-Sánchez E, et al. Menstrual hygiene management among women and adolescent girls in the aftermath of the earthquake in Nepal. BMC Women Health 2018; 18:1-8.

- Sommer M, Caruso BA, Torondel B, et al. Menstrual hygiene management in schools: Midway progress update on the “MHM in Ten” 2014–2024 global agenda. Health Res Policy Syst 2021; 19:1-4.

- Sivakami M, van Eijk AM, Thakur H, et al. Effect of menstruation on girls and their schooling, and facilitators of menstrual hygiene management in schools: surveys in government schools in three states in India, 2015. J Glob Health 2019; 9.

- Dündar T, Özsoy S. Menstrual hygiene management among visually impaired women. British J Visual Impairment 2020; 38:347-362.

- Rheinländer T, Gyapong M, Akpakli DE, et al. Secrets, shame and discipline: School girls' experiences of sanitation and menstrual hygiene management in a peri-urban community in Ghana. Health Care Women Int 2019; 40:13-32.

- Chew KS, Wong SS, Hassan AK, et al. Development of a validated instrument on socio-cultural and religious influences during menstruation in Malaysia. Med J Malaysia 2021; 76:814-819.

- Chew KS, Wong SS, Hassan AK, et al. Socio-cultural and religious influences during menstruation among university students. Res Square 2020; 1.

- Morowatisharifabad MA, Vaezi A, Bokaie M, et al. Cultural beliefs on menstrual health in Bam city: A qualitative study. Int J Pediatr 2018; 6:8765-8778.

- Foster J, Montgomery P. Absorbency of biodegradable materials for menstrual hygiene management products in low-and middle-income countries. Res Square 2021.

- Shibly M, Hassan M, Hossain MA, et al. Development of biopolymer-based menstrual pad and quality analysis against commercial merchandise. Bull National Res Centre 2021; 45:1-3.

- Van Eijk AM, Zulaika G, Lenchner M, et al. Menstrual cup use, leakage, acceptability, safety, and availability: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Public Health 2019; 4:376-393.

- Tudu PN. Saathi sanitary pads: Eco‐friendly pads which will make you go bananas! Int J Nonprofit Voluntary Sector Marketing 2020; 25:e1667.

- Roxburgh H, Hampshire K, Kaliwo T, et al. Power, danger, and secrecy—A socio-cultural examination of menstrual waste management in urban Malawi. Plos One 2020; 15:e0235339.

- Balla CP, Nallapu SS. Knowledge, perceptions and practices of menstrual hygiene among degree college students in Guntur city of Andhra Pradesh, India. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol 2018; 7:4109-4115.

- Bhor G, Ponkshe S. A decentralized and sustainable solution to the problems of dumping menstrual waste into landfills and related health hazards in India. Eur J Sust Dev 2018; 7:334.

- Morrison JL, Basnet M, Anju B, et al. Girls’ menstrual management in five districts of Nepal: Implications for policy and practice. Studies Social Justice 2018; 12:252-272.

- Mahajan T. Imperfect information in menstrual health and the role of informed choice. Indian J Gend Stud 2019; 26:59-78.

- Feston BN, Krishnaraj S. Creating awareness on menstrual hygiene practices in Kerala: Programs and practices through strategic movement from SMKC (Sustainable Menstruation Kerala Collective). Asia Pacific J Res 2018; 105.

- Alda-Vidal C, Browne AL. Absorbents, practices, and infrastructures: Changing socio-material landscapes of menstrual waste in Lilongwe, Malawi. Soc Cult Geogr 2022; 23:1057-1077.

- Schmitt ML, Wood OR, Clatworthy D, et al. Innovative strategies for providing menstruation-supportive water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) facilities: learning from refugee camps in Cox’s bazar, Bangladesh. Confl Health 2021; 15:1-2.

- Sinha RN, Paul B. Menstrual hygiene management in India: The concerns. Indian J Public Health 2018; 62:71.

- Hennegan J, Nansubuga A, Akullo A, et al. The Menstrual Practices Questionnaire (MPQ): Development, elaboration, and implications for future research. Global Health Action 2020; 13:1829402.

- Miller V, Winkler IT. Transnational engagements: Menstrual health and hygiene—Emergence and future directions. Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies 2020; 653.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Author Info

Department of History, Thiruvalluvar Government Arts College, Rasipuram, IndiaReceived: 01-Nov-2022, Manuscript No. jrmds-22-79272; , Pre QC No. jrmds-22-79272(PQ); Editor assigned: 03-Nov-2022, Pre QC No. jrmds-22-79272(PQ); Reviewed: 17-Nov-2022, QC No. jrmds-22-79272(Q); Revised: 21-Nov-2022, Manuscript No. jrmds-22-79272(R); Published: 28-Nov-2022