Research - (2022) Volume 10, Issue 5

Most Common Shades Used For Class V Anterior Restoration

Aarthi Muthukumar and Vigneshwar T*

*Correspondence: Vigneshwar T, Department of Endodontics, Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha University, Chennai, India, Email:

Abstract

Objective: The study's goal is to identify the shade choices and determine the most commonly chosen shade for class V restoration, as well as determining the impact of gender and age on shade selection. Introduction: The perception of colour and appearance of teeth is a complex phenomenon, with numerous factors such as lighting conditions, translucency, opacity, light scattering, gloss and the human eye and brain affecting the overall outcome of tooth colour. Any slight change in shade from the natural, may play with our eyes, our minds and also our dentistry at large. Therefore, selecting the proper shade and colour match to natural dentition is still one of the most difficult and frustrating problems. Materials and methods: Case sheet records of patients who had visited Saveetha Dental College and Hospital between January 2020 and January 2021 were reviewed. 3911 patients treated with class 5 restoration were included in the study. Age, gender and composite shade used were collected. The collected data were analyzed using SPSS statistical software. Descriptive statistics (percentage, mean, SD) and inferensial test (Chi square test) were performed. Results: 40-60 years age group (58%) is the most common age group to undergo class v restorations when compared to other age groups. 73% of males and 27% of females were included in the study. Thus males undergo class v restorations more commonly than females. A2 is the most commonly used shade (73%) when compared to other shades and also A2 is the most commonly used shade for class v anterior restoration irrespective of age and gender. Conclusion: This study showed that shade A2 was the most frequently selected shade for aesthetic class v restoration followed by the A1 shade. The least favoured being the shade B3. A2 is the most commonly used shade for class v anterior restorations irrespective of age and gender.

Keywords

Anterior restoration, Composite, class v, Shade matching, Common shade

Introduction

Because of their high incidence and accompanying unfavourable clinical problems, such as aesthetic impairment and dental sensitivity, noncarious cervical lesions (NCCLs) have long been a source of concern for patients and physicians [1-3]. Abrasion, acid erosion, and abfraction are the most common etiologic causes identified in the literature. Abrasion is the mechanical wear of hard tissues that is most usually connected with teeth brushing and abrasive dentifrices, but other causes may also be involved [4]. Erosion is the nonbacterial acidic breakdown of the crystalline minerals hydroxyapatite and fluorapatite, which are found in enamel and dentin, respectively [5]. Despite the fact that the term "erosion" is frequently used in the dental literature, a recent paper suggested that the term "biocorrosion" be used instead because it better describes tooth substance degradation caused by chemical, biochemical, and electrochemical degradation caused by exogenous and endogenous acids, proteolytic agents, and piezoelectric effects [6].

Abfraction NCCLs are caused by biomechanical loading forces acting on teeth and focusing at the cementoenamel junction, eventually causing teeth to flex, fatigue, and lose enamel and dentin, resulting in wedge-shaped lesions [7]. NCCLs are thought to be caused by cyclic fatigue and biocorrosion, according to evidence [8]. It is the consequence of a combination of bio corrosive, stress, and attrition mechanisms that interact to cause lesions of varied extent. These lesions can range in appearance from shallow saucer-like depressions to large disk- shaped lesions or wedge-shaped lesions, depending on their location and cause. The floor of the defect could be flat, indented, or severely angled [9].

The natural tooth is polychromatic, which means it contains a wide range of hues and nuances that the human brain can see and interpret [2,10, 11]. It's not usually easy to artificially duplicate all of the tooth's intrinsic qualities. To identify intricacies and identify the distinct nuances of each tooth, the dentist should have an artistic sense. This clinical stage is clearly more than just picking a letter A or B and a number 1 or 2, and it has a direct and considerable impact on the ultimate aesthetic outcome [11].

The interaction of three dimensions known as hue, chroma, and value [11,12] should be understood as the consequence of colour. The main name of the colour observed by the viewer, such as green, red, yellow, or blue, is defined as hue. Colors are represented by letters on resin tubes in dentistry (A, B, C and D). Chroma is defined as the degree of saturation or intensity of a hue, such as light blue, dark blue, or royal blue, and it is represented in dentistry by numbers in a crescent order. Value denotes the dynamic dimension of the bodies, corresponds to the color's luminosity, and is proportional to the amount of white or black pigments present [10,13].

Color choosing should be done with clean teeth and the oral cavity's natural humidity. Water plays a crucial influence in the final colour output, hence this is required. Dehydration diminishes the translucency of the enamel by 82 percent, forcing the doctor to choose a resin that is lighter and more opaque than the natural tooth colour. The exchange of water by air around the enamel prisms causes the influence of water on enamel translucence. Because light refracts differently in water (1.33) and air (1.0), drying the enamel causes air to surround the interprismatic gaps, causing the tooth to seem lighter and more opaque [4]. Our team has extensive knowledge and research experience that has translated into high quality publications [14-23], [24-27], [28-32] [33]. The aim of this study was to find the most commonly used shade for anterior class V restorations.

Materials and Methods

The study was done as a retrospective, single centered study. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Committee (Ethical approval number. SDC/ SIHEC/ 2020/ DIASDATA/ 0619-0320). We reviewed case records of the data of 86000 patients who had visited Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals between January 2020 and January 2021. Incomplete data were excluded. A sample of 3911 patients treated with class 5 restoration was included in the study. Age, gender and composite shade used were collected. These data were cross verified with photographs. The collected data were analysed using SPSS statistical software. Descriptive statistics (percentage, mean, SD) and inferential test (Chi-square test) were done appropriately.

Results and Discussion

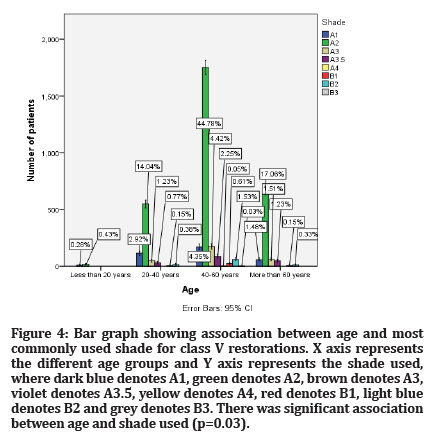

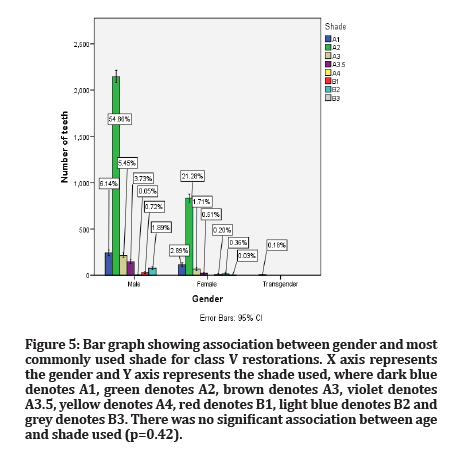

40-60 years age group (58%) is the most common age group to undergo class v restorations when compared to other age groups. 73% of males and 27% of females were included in the study. Thus males undergo class v restorations more commonly than females. A2 is the most commonly used shade (73%) when compared to other shades and also A2 is the most commonly used shade for class v anterior restoration irrespective of age and gender (Figures 1-5).

Figure 1: About 1% of the study population were less than 20 years, 19% of study population were 20-40 years old, 58% were 40-60 years old and 22% were more than 60 years old.

Figure 2: 73% of the study populations were males and 27% were females. Thus males undergo anterior class 5 restoration more than females.

Figure 3: 76% of the study population were treated with A2 shade composite for anterior class v restoration.

Figure 4: Bar graph showing association between age and most commonly used shade for class V restorations. X axis represents the different age groups and Y axis represents the shade used, where dark blue denotes A1, green denotes A2, brown denotes A3, violet denotes A3.5, yellow denotes A4, red denotes B1, light blue denotes B2 and grey denotes B3. There was significant association between age and shade used (p=0.03).

Figure 5:Bar graph showing association between gender and most commonly used shade for class V restorations. X axis represents the gender and Y axis represents the shade used, where dark blue denotes A1, green denotes A2, brown denotes A3, violet denotes A3.5, yellow denotes A4, red denotes B1, light blue denotes B2 and grey denotes B3. There was no significant association between age and shade used (p=0.42).

The shade matching method is a crucial step in cosmetic restorations that requires utmost attention. In order to match the perfect hue, the clinician's knowledge and experience are crucial. To choose the right shade and restore aesthetics, one must first understand the most commonly used shade. Understanding of the distribution of shades may be a useful adjunct in tooth shade matching. With more research and new technologies, there is the possibility of achieving a greater percentage of successful shade match than what we have currently [2]. Different range of shades exists for shade guides used in the dental Clinics and Dental Laboratories depending on the manufacturers of the shade guide. Distribution of the shade selected for restorations may be influenced by a number of factors such as the type of shade guide, experience of the operator, technique and light condition of the operatory [9]. The results of some research indicate that the most frequently chosen shades were in the mid-range of reddish-brown hue, but shades in the reddish-grey range of hue were rarely chosen [12]. However, it has been shown that there was a statistically significant difference between the different individuals with respect to shade selection ability [34]. There may be a need for blending of more than one shade in certain situations. Although, the selection of more than one shade was generally restricted to the maxillary anterior teeth [12]; perhaps being the most visible teeth in the aesthetic zone of the mouth.

The tooth shade chosen for aesthetic advanced restorations manufactured over a seven-year period in a tertiary hospital in Nigeria was examined in this study. According to the findings, the most popular shade group was 'A' (orange hue), with shade A2 being the most popular. In their own survey, Smith and Wilson of Manchester's University Dental Hospital found that the same hue A2 was the most popular [12]. Using the 3D master shade guide, Christina Gomez-Polo et al. concluded that the most prevalent hue is M in their study [35] on the Spanish population. The least popular shade in this study was the vita shade B group, which is consistent with Smith and Wilson's study [12], which found that the reddish-grey hue range (vita classical dental shade guide B group) was rarely picked. Females preferred lighter colours than their male counterparts, with 57 percent choosing A shade for their repair and only 7% choosing D shade. This is corroborated by the findings of Xiao et al. [36], who found that female teeth were lighter and less yellow than male teeth.

The patient's age appears to have an affect on the hue of their prosthesis. The younger age group (15-45) had a lighter hue than the older group, according to the current study. This is supported by a study by Xiao et al., [36] who found a rise in CIEb* and a decrease in CIEL* as people get older. Hasegawa et al. [11] discovered that CIEb* has a substantial positive correlation and CIEL* has a significant negative correlation. In general, much research, including the current one, concur that tooth colour darkens as one gets older. This could be owing to the shade being influenced by the underlying dentine's greater thickness, as well as enamel weakening due to tooth attrition as people become older [10].

Conclusion

This study showed that shade A2 was the most frequently selected shade for aesthetic class v restoration followed by the A1 shade. The least favoured being the shade B3. A2 is the most commonly used shade for class v anterior restorations irrespective of age and gender.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the support rendered by the Department of Prosthodontics & Saveetha dental college and hospitals and the management.

Author Contribution

All the authors contributed equally to the study.

Source of Funding

The present project is supported/funded/sponsored by Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha University Kumaran TV center and Furnitures, Attur, Salem.

Conflict of Interest

The author has no conflict of interest.

References

- Miller N, Penaud J, Ambrosini P, et al. Analysis of etiologic factors and periodontal conditions involved with 309 abfractions. J Clin Periodontol 2003; 30:828-832.

- Osborne-Smith KL, Burke FJ, Wilson NH. The aetiology of the non-carious cervical lesion. Int Dent J 1999; 49:139-143.

- Wood I, Jawad Z, Paisley C, et al. Non-carious cervical tooth surface loss: a literature review. J Dent 2008; 36:759-766.

- Litonjua LA, Andreana S, Cohen RE. Toothbrush abrasions and noncarious cervical lesions: evolving concepts. Compend Contin Educ Dent 2005; 26:767-776.

- Bassiouny MA. Effects of common beverages on the development of cervical erosion lesions. Gen Dent 2009; 57:212-3.

- Grippo JO, Simring M, Coleman TA. Abfraction, abrasion, biocorrosion, and the enigma of noncarious cervical lesions: a 20-year perspective. J Esthet Restor Dent 2012; 24:10-23.

- Grippo JO. Abfractions: a new classification of hard tissue lesions of teeth. J Esthet Dent 1991; 3:14-9.

- Grippo JO, Chaiyabutr Y, Kois JC. Effects of cyclic fatigue stress-biocorrosion on noncarious cervical lesions. J Esthet Restor Dent 2013; 25: 265-272.

- Levitch LC, Bader JD, Shugars DA, et al. Non-carious cervical lesions. J Dent 1994; 22:195-207.

- Terry DA. Dimensions of color: creating high-diffusion layers with composite resin. Compend Contin Educ Dent 2003; 24:3-13.

- Vanini L. Light and color in anterior composite restorations. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent 1996; 8:673-82.

- Magne P, Holz J. Stratification of composite restorations: systematic and durable replication of natural aesthetics. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent 1996; 8:61-8.

- Franco EB, Francischone CE, Medina-Valdivia JR, et al. Reproducing the natural aspects of dental tissues with resin composites in proximoincisal restorations. Quintessence Int 2007; 38: 505-510.

- Muthukrishnan L. Imminent antimicrobial bioink deploying cellulose, alginate, EPS and synthetic polymers for 3D bioprinting of tissue constructs. Carbohydr Polym 2021; 260:117774.

- PradeepKumar AR, Shemesh H, Nivedhitha MS, et al. Diagnosis of Vertical Root Fractures by Cone-beam Computed Tomography in Root-filled Teeth with Confirmation by Direct Visualization: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Endod 2021; 47:1198â??1214.

- Chakraborty T, Jamal RF, Battineni G, et al. A review of prolonged post-COVID-19 symptoms and their implications on dental management. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18:5131.

- Muthukrishnan L. Nanotechnology for cleaner leather production: A review. Environ Chem Lett 2021; 19:2527-49.

- Teja KV, Ramesh S. Is a filled lateral canal - A sign of superiority? J Dent Sci 2020; 15:562-563.

- Narendran K, MS N, Sarvanan A. Synthesis, Characterization, Free Radical Scavenging and Cytotoxic Activities of Phenylvilangin, a Substituted Dimer of Embelin. Indian J Pharm Sci 2020; 82:909-12.

- Reddy P, Krithikadatta J, Srinivasan V, et al. Dental Caries Profile and Associated Risk Factors Among Adolescent School Children in an Urban South-Indian City. Oral Health Prev Dent 2020; 18:379-386.

- Sawant K, Pawar AM, Banga KS, et al. Dentinal Microcracks after Root Canal Instrumentation Using Instruments Manufactured with Different NiTi Alloys and the SAF System: A Systematic Review. NATO Adv Sci Inst Ser E Appl Sci 2021; 11:4984.

- Bhavikatti SK, Karobari MI, Zainuddin SL, et al. Investigating the Antioxidant and Cytocompatibility of Mimusops elengi Linn Extract over Human Gingival Fibroblast Cells. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18:7162.

- Karobari MI, Basheer SN, Sayed FR, et al. An In Vitro Stereomicroscopic Evaluation of Bioactivity between Neo MTA Plus, Pro Root MTA, BIODENTINE & Glass Ionomer Cement Using Dye Penetration Method. Materials 2021; 14:3159.

- Rohit Singh T, Ezhilarasan D. Ethanolic Extract of Lagerstroemia Speciosa (L.) Pers., Induces Apoptosis and Cell Cycle Arrest in HepG2 Cells. Nutr Cancer 2020; 72: 146â??156.

- Ezhilarasan D. MicroRNA interplay between hepatic stellate cell quiescence and activation. Eur J Pharmacol 2020; 885:173507.

- Romera A, Peredpaya S, Shparyk Y, et al. Bevacizumab biosimilar BEVZ92 versus reference bevacizumab in combination with FOLFOX or FOLFIRI as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 3:845â??855.

- Raj RK. Ã?-Sitosterol-assisted silver nanoparticles activates Nrf2 and triggers mitochondrial apoptosis via oxidative stress in human hepatocellular cancer cell line. J Biomed Mater Res A 2020; 108:1899-1908.

- Vijayashree Priyadharsini J. In silico validation of the non-antibiotic drugs acetaminophen and ibuprofen as antibacterial agents against red complex pathogens. J Periodontol 2019; 90:1441-1448.

- Priyadharsini JV, Vijayashree Priyadharsini J, Smiline Girija AS, et al. In silico analysis of virulence genes in an emerging dental pathogen A. baumannii and related species. Arch Oral Biol 2018; 94:93-98.

- Uma Maheswari TN, Nivedhitha MS, Ramani P. Expression profile of salivary micro RNA-21 and 31 in oral potentially malignant disorders. Braz Oral Res 2020; 34: e002.

- Gudipaneni RK, Alam MK, Patil SR, et al. Measurement of the Maximum Occlusal Bite Force and its Relation to the Caries Spectrum of First Permanent Molars in Early Permanent Dentition. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2020; 44:423-28.

- Chaturvedula BB, Muthukrishnan A, Bhuvaraghan A, et al. Dens invaginatus: a review and orthodontic implications. Br Dent J 2021; 230: 345â??350.

- Kanniah P, Radhamani J, Chelliah P, et al. Green synthesis of multifaceted silver nanoparticles using the flower extract of Aerva lanata and evaluation of its biological and environmental applications. ChemistrySelect 2020; 5:2322-31.

- Haralur SB, Al-Shehri KS, Assiri HM, et al. Influence of personality on tooth shade selection. Int J Esthet Dent 2016; 11:126-137.

- Gómez-Polo C, Gómez-Polo M, MartÃnez Vázquez de Parga JA, et al. Study of the most frequent natural tooth colors in the Spanish population using spectrophotometry. J Adv Prosthodont 2015; 7: 413-422.

- Xiao J, Zhou XD, Zhu WC, et al. The prevalence of tooth discolouration and the self-satisfaction with tooth colour in a Chinese urban population. J Oral Rehabil 2007; 34:351â??360.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Author Info

Aarthi Muthukumar and Vigneshwar T*

Department of Endodontics, Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha University, Chennai, IndiaCitation: Aditya Jain, Anjaneyulu, Most Common Shades Used For Class V Anterior Restoration, J Res Med Dent Sci, 2022, 10 (5):46-50.

Received: 03-May-2022, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-60229; , Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-60229 (PQ); Editor assigned: 05-May-2022, Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-60229 (PQ); Reviewed: 19-May-2022, QC No. JRMDS-22-60229; Revised: 24-May-2022, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-60229 (R); Published: 31-May-2022