Research - (2021) Volume 9, Issue 5

Study of Serum Uric Acid Levels in Acute Myocardial InfarctionPatients

Abhishek Das and SMKS Gurukul*

*Correspondence: SMKS Gurukul, Department of General Medicine, Sree Balaji Medical College and Hospital Affiliated to Bharath Institute of Higher Education and Research, India, Email:

Abstract

The present study has been undertaken with the following High uric acid level is a negative prognostic factor in patients with myocardial infarction. In myocardial infarction higher the uric acid level increases the risk of mortality rate. There is uncertainty about the role of uric acid in acute coronary syndrome and whether it could be used as a prognostic marker in MI patients. A detailed clinical examination was performed in all patients. 100 patients of acute myocardial infarction who fulfilled inclusion/exclusion criteria were enrolled for the study. Thirty three percent patients were known diabetic in our study. Non-diabetic and diabetic patients had comparable serum uric acid levels on Day-0 This finding is consistent with study which there was no significant association between serum uric acid level and diabetic status. However, this finding contrasts with other study which showed that hyper uricemia is significantly associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Twenty one percent patients had history of ischemic heart disease. There was significant difference between serum uric acid concentration at the time of admission and h/o ischemic heart disease.

Keywords

Myocardial infarction, Acute coronary, Uric acid, Troponin

Introduction

Clinical and epidemiological studies have proved that serum uric acid (SUA) is significantly correlated with cardiovascular disease. Increased SUA is significantly associated with the occurrence and mortality of coronary artery disease [1]. But few studies have investigated serum uric acid levels in patients with acute myocardial infarction. This study was undertaken to assess the clinical value of serum uric acid levels in patients with MI by confirming diagnosis by their clinical characteristics, ECG and biomarkers (Troponin-T, CPK, CPK-MB). Previous trials suggest that uric acid might bOe an independent predictor of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in patients with coronary artery disease or only an indirect marker of adverse event due to the association between uric acid and other cardiovascular risk factors [- 4SJ [2,3]. Several theories have been discussed, such as high serum uric acid has impact on increasing platelet reactivity. There is uncertainty about the role of uric acid in acute coronary syndrome and whether it could be used as a prognostic marker in MI patients. Furthermore, there is a need to find a simple and accurate prognostic marker that could be used in a remote area where fibrinolytic therapy is the first choice of acute reperfusion therapy (as part of pharmaco invasive strategy) in non- PCI capable hospitals especially in developing countries [4-6].

Following myocardial infarction (MI) some proteins and enzymes labeled as cardiac markers (CPK - MB/ Troponin T) are released into the blood in large quantity from necrotic heart muscle. These markers viz. CPKMB, Troponin-T, Troponin-I and myoglobin, have specific temporal profile in relation to MI; however, they do not correlate with myocardial function. Epidemiological studies have recently shown that uric acid may be a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases and a negative prognostic marker for mortality in subjects with pre-existing heart failure. Elevated serum uric acid is highly predictive of mortality in patients with heart failure or coronary artery disease and of cardiovascular events in patients [7,8].

MI usually occurs when coronary blood flow decreases abruptly after a thrombotic occlusion of a coronary artery previously affected by atherosclerosis. Slowly developing, highgrade coronary artery stenosis do not typically precipitate MI because of the development of a rich collateral network over time. Instead, MI occurs when a coronary artery thrombus develops rapidly at a site of vascular injury. MI occurs when the surface of an atherosclerotic plaque becomes disrupted (exposing its contents to the blood) and conditions (local or systemic) favour thrombogenesis. A mural thrombus forms at the site of plaque disruption, and the involved coronary artery becomes occluded. Histologic studies indicate that the coronary plaques prone to disruption are those with a rich lipid core and a thin fibrous [9-11]. The coagulation cascade is activated on exposure of tissue factor in damaged endothelial cells at the site of the disrupted plaque. Factors VII and X are activated, ultimately leading to the conversion of prothrombin to thrombin, which then converts fibrinogen to fibrin. Fluidphase and clot-bound thrombin participate in an auto amplification reaction leading to further activation of the coagulation cascade. The culprit coronary artery eventually becomes occluded by a thrombus containing platelet aggregates and fibrin strands [12].

Materials and Methods

We studied patients more than 30 years of age who were diagnosed as ST segment elevation acute myocardial infarction (STEMI) or non-ST segment elevation acute myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) based on clinical history, examination, ECG changes, biochemical markers, and admitted m Sree Balaji Medical College and Hospital, during September 2011- JUNE 2013.

Inclusion criteria for patients

Patients brought to hospital with history of chest pain and diagnosed as myocardial infraction (both STEMI and NSTEMI)

Diagnosis was confirmed by.

ECG.

Biochemical markers like Troponin-T, Creatine Kinase (CK-MB) test CPK.

Exclusion criteria

Any patient with a condition known to elevate uric acid level e.g.

✓ Chronic Kidney Disease.

✓ Gout.

✓ Haematological malignancy.

✓ Hypothyroidism were excluded.

Also patients on drugs which increase serum uric acid e.g.

✓ Salicylates (>2 gm/d).

✓ Diuretics.

✓ Ethambutol.

✓ Pyrazinamide and also chronic alcoholics were excluded.

Written consent was obtained from both patients and control. Detailed history regarding symptoms and duration of the chest pain kidney disease, hypertension, diabetes, smoking, alcoholism, drug intake and treatment were elicited. A detailed clinical examination was performed in all patients. 100 patients of acute myocardial infarction who fulfilled inclusion/ exclusion criteria were emolled for the study. A detailed history and physical examination with special reference to Killip class was carried out. All patients underwent routine investigations including Hb, CBC, renal function tests, liver function tests, ECG, chest X-ray. Patients were treated as decided by attending physician. Patients were followed up till hospital stay i.e., 7 days. Serum uric acid level was measured on day 0, 3 & 7 of ML 50 age and sex matched healthy controls were also be evaluated for baseline serum uric acid level. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the hospital. A detailed statistical analysis was carried out. Basal serum uric acid levels were compared with controls with unpaired 't' test. The levels of serum uric acid on day 0, 3, 7 were compared by paired 't' test. Uric acid levels and Killip class was compared with coefficient of correlation.

Results

Results are explained in the form of tables (Tables1 to Table 11 and Figure 1 and Figure 2.

| Variable | Group | N | Mean | Std.Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Case | 100 | 64.4 | 7.72 |

| Control | 50 | 62.06 | 13.307 |

Table 1: Mean age between cases and controls.

| Variable | Group | N | Mean | Std. Dev | p.Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uric acid at Day 0 | Case | 100 | 5.123 | 1.5198 | <0.001 |

| Control | 50 | 3.698 | 0.4415 | ||

| Average uric acid level in control group is 3.69 and in case group was 5.12 | |||||

Table 2: Mean uric acid at day 0 between cases and controls.

| Gender | Group | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case | Control | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Male | 62 | 62 | 26 | 52 | 88 | 58.7 |

| Female | 38 | 38 | 24 | 48 | 62 | 41.3 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 50 | 100 | 150 | 100 |

Table 3: Comparison of sex ratio between cases and controls.

| Variable | Gender | N | Mean | Std. Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uric acid at Day 0 | Male | 62 | 4.977 | 1.4468 |

| Female | 38 | 5.361 | 1.6234 |

Table 4: Comparison of the mean uric acid at day O between genders among cases.

| Variable | DM | N | Mean | Std. Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uric acid at Day 0 | Yes | 34 | 5.085 | 1.6817 |

| No | 66 | 5.142 | 1.4425 |

Table 5: Comparison of the mean uric acid between diabetes mellitus and non-DM among cases.

| Killip class at day 3 | N | Mean | Std. Dev | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | 59 | 4.158 | 0.8186 | <0.001 |

| II | 11 | 4.909 | 1.288 | |

| III | 8 | 5.388 | 1.5842 | |

| IV | 20 | 7.54 | 1.06 | |

| Total | 98 | 5.033 | 1.6574 |

Table 6: Comparison of the mean Uric acid levels between Killip classes at day 3.

| Killip class at Day 3 | Uric acid level at Day 3 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 4.1 - 5.5 | 5.6 - 7.0 | > 7.0 | Total | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| I | 34 | 87.2 | 23 | 74.2 | 2 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 59 | 60.2 |

| II | 3 | 7.7 | 5 | 16.1 | 2 | 20 | 1 | 5.6 | 11 | 11.2 |

| III | 2 | 5.1 | 2 | 6.5 | 3 | 30 | 1 | 5.6 | 8 | 8.2 |

| IV | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3.2 | 3 | 30 | 16 | 88.9 | 20 | 20.4 |

| Total | 39 | 100 | 31 | 100 | 10 | 100 | 18 | 100 | 98 | 100 |

Table 7: Comparison of the proportions between Killip class and Uric acid at day 3.

| Mortality | IHD/SHTN | Total | p.Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Survived | 110 | 96.5 | 33 | 91.7 | 143 | 95.3 | 0.359 |

| Died | 4 | 3.5 | 3 | 8.3 | 7 | 4.7 | |

| Total | 114 | 100 | 36 | 100 | 150 | 100 | |

Table 8: Comparison of mortality among IHD/SHTN.

| DM | Total | P Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | 5 | 6 | ||||

| Mortality | N | % | N | % | N | % | 0.694 |

| Survived | 94 | 95.9 | 49 | 94.2 | 143 | 95.3 | |

| Died | 4 | 4.1 | 3 | 5.8 | 7 | 4.7 | |

| Total | 98 | 100 | 52 | 100 | 150 | 100 | |

Table 9: Comparison of mortality among DM.

| DM | Total | P Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||||||

| IHD/SHTN | N | % | N | % | N | % | 0.311 |

| No | 77 | 78.6 | 37 | 71.2 | 114 | 76 | |

| Yes | 21 | 21.4 | 15 | 28.8 | 36 | 24 | |

| Total | 98 | 100 | 52 | 100 | 150 | 100 | |

Table 10: Comparison of IHD/SHTN among DM.

| Mortality at day 7 | N | Mean | Std. Deviation | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uric acid | Died | 7 | 6.757 | 1.4199 | <0.001 |

| Survived | 143 | 4.545 | 1.3561 |

Table 11: Comparison of mean Uric acid values between mortality at day 7.

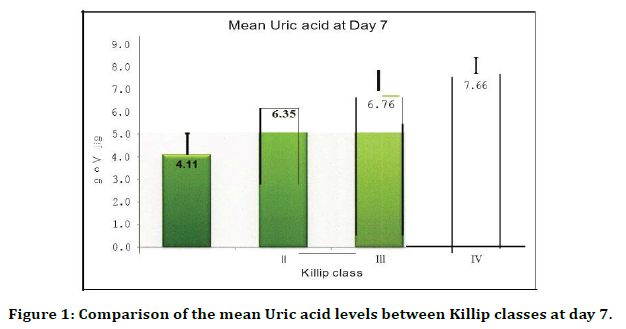

Figure 1. Comparison of the mean Uric acid levels between Killip classes at day 7.

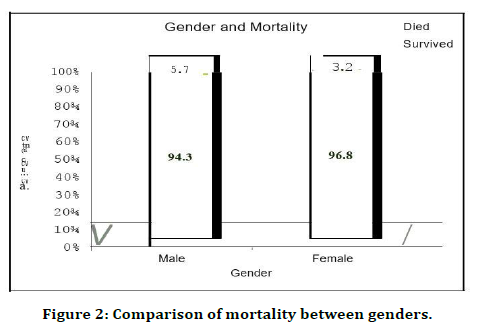

Figure 2. Comparison of mortality between genders.

Discussion

Previous studies have shown that serum uric acid increases in cardiac failure. In a study done it was shown that serum uric acid levels correlate with Killip classification. Combination of Killip class and serum uric acid level after acute myocardial infarction is a good predictor of mortality in patients who have acute myocardial infarction [13]. Using this study as referral study, we tried to find correlation between serum uric acid and Killip class and their prognostic value in our patients. Present study was conducted in 100 patients of acute myocardial infarction, who presented to hospital with in 24 hrs of onset of symptoms. Fifty age and sex matching healthy controls were also evaluated for comparison of uric acid levels. Out of 100 patients, 65 had ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), while 35 patients were of non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI). Sixty-one patients were thrombolysed while four were not thrombolysed due to delayed presentation. Uric acid was treated as a continuous variable and as a categorical variable, and variables were divided into quartiles according to serum uric acid concentrations same as in referral study by Kojima et al.43 Our patients and controls were age and sex matched [14,15].

The patients had higher serum uric acid level probably because of acute myocardial infarction. Similar finding was seen in a referral study44 with 1124 patients who presented with acute myocardial infarction within 48 hrs. of onset of symptoms. In our study there was no difference in uric acid levels between male and female patients however in referral study males had higher uric acid levels as compared to females43 correlation (p=0.241) between serum uric acid level and patients who were known or found to be hypertensive on admission [16,17]. This is different than other studies which showed that hypertensive patients had more hyperuricemia [18]. Thirty three percent patients were known diabetic in our study. Non-diabetic and diabetic patients had comparable serum uric acid levels on Day-0 This finding is consistent with study which there was no significant association between serum uric acid level and diabetic status. However, this finding contrasts with other study which showed that hyperuricaemia is significantly associated with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Twenty one percent patients had history of ischemic heart disease [19]. There was significant difference between serum uric acid concentration at the time of admission and h/o ischemic heart disease. Serum uric acid levels were higher in patients with history of IHD as seen in previous study. Also, Killip classification is indicator of severity of heart failure [20]. There was a correlation between serum uric acid level and Killip class on day of admission as in earlier study43 Previous studies have shown that serum uric acid level increases in cardiac failure. In our study serum uric acid levels correlate with severity of cardiac failure. There was statistically significant correlation found between serum uric acid level and Killip class (p=0.001) on day 3 and. Patients of Killip class lll and IV had higher levels of uric acid as compared to patients of class 1 and 11. This finding is consistent with referral study [21]. There is statistically significant association (p=<0.05) between serum creatinine on day of admission and Killip class, in our study. There is graded relation between serum uric acid concentration and creatinine concentration in patients of acute myocardial infarction. Out of 100 patients, seven expired for 7 day follow up. All the patients who died had serum uric acid level more than 7.0 mg/dL. Of these seven patients, one was in Killip class III, one in killip class II and five were in Killip class IV at the time of admission. Thus, out of 7 patients who died were in higher class i.e., class IV at time of admission. one patient of Killip class II and one in Killip class III shifted to Killip class IV on day three [21]. Serum uric acid levels and Killip class are influenced significantly by previous myocardial infarction. Patients who had myocardial infarction in past have higher serum uric acid levels and are in higher Killip class. Combination of Killip class and serum uric acid level after acute myocardial infarction is a good predictor of mortality after AMI.

Conclusion

Uric Acid levels were high in patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. Patients who were in higher Killip classification had higher uric acid levels Patients who died had higher uric acid levels. Patients who survived had lower uric acid level. No significant difference in uric acid level in diabetes mellitus patients and non-diabetic mellitus patients. No significant difference in uric acid level in patients with systemic hypertension and patients who does not have systemic hypertension.

Funding

No funding sources.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The encouragement and support from Bharath University, Chennai, is gratefully acknowledged. For provided the laboratory facilities to carry out the research work.

References

- Baker JF, Krishnan E, Chen L, et al. Serum uric acid and cardiovascular disease: recent developments, and where do they leave us? Am J Med 2005; 118:816-826.

- Brodov Y, Chouraqui P, Goldenberg I, et al. Serum uric acid for risk stratification of patients with coronary artery disease. Cardiology 2009; 114:300-305.

- Freedman DS, Williamson DF, Gunter EW, et al. Relation of serum uric acid to mortality and ischemic heart disease: The NHANES I epidemiologic follow up study. Am J Epidemiol 1995; 141: 37-644.

- Wannamethee SG, Shaper AG, Whincup PH. Serum urate and the risk of major coronary heart disease events. Heart 1997; 78:147-153.

- Culleton BF, Larson MG, Kannel WB, et al. Serum uric acid and risk for cardiovascular disease and death: the Framingham Heart Study. Ann Intern Med 1999; 131:7-13.

- Bickel C, Rupprecht HJ, Blankenberg S, et al. Serum uric acid as an independent predictor of mortality in patients with angiographycally proven coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 2002; 89:12-17.

- Vitart V, Rudan I, Hayward C, et al. "SLC2A9 is a newly identified urate transporter influencing serum urate concentration, urate excretion and gout". Nature Genetics 2008; 40 (4): 437-42.

- Kolz M, Johnson T, Sanna S, et al. Meta-analysis of 28,141 individuals identifies common variants within five new loci that influence uric acid concentrations. PLoS Genet 2009; 5:e1000504.

- Köttgen A, Albrecht E, Teumer A, et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify 18 new loci associated with serum urate concentrations. Nature Genet 2013; 45:145-154.

- Doring A, Gieger C, Mehta D, et al. SLC2A9 influences uric acid concentrations with pronounced sex-specific effects. Nature Genet 2008; 40:430-436.

- Heinig M, Johnson RJ. Role of uric acid in hypertension, renal disease, and metabolic syndrome. Cleveland Clin J Med 2006; 73:1059-64.

- Castelli P, Condemi AM, Brambillasca C, et al. Improvement of cardiac function by allopurinol in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 1995; 25:119-125.

- Anker SD, Doehner W, Rauchhaus M, et al. Uric acid, and survival in chronic heart failure: validation and application in metabolic, functional, and haemodynamic staging. Circulation 2003; 22:1991-1997.

- Ochiai ME, Barretto AC, Oliveira MT, et al. Uric acid renal excretion and renal in sufficiency in decompensated severe heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2005; 7:468-474.

- Festa A, Haffner SM. Inflammation, and cardiovascular disease m patients with diabetes: Lessons from the diabetes control.

- Hare JM, Johnson RJ. Uric acid predicts clinical outcomes in heart failure: Insights regarding the role of xanthine oxidase and uric acid in disease pathophysiology. Circulation 2003; 107:1951-1953.

- Fang J, Alderman MH. Serum uric acid and cardiovascular mortality: The NHANES I epidemiologic follow-up study, 1971-1992. JAMA 2000; 283:2404-2410.

- Guthikonda S, Sinkey C, Barenz T, et al. Xanthine oxidase inhibition reverses endothelial dysfunction in heavy smokers. Circulation 2003; 107:416-421.

- Farquharson CA, Butler R, Hill A, et al. Allopurinol improves endothelial dysfunction in chronic heart failure. Circulation 2002; 106:221-226.

- Anker SD, Doehner W, Rauchhaus M, et al. Uric acid, and survival in chronic heart failure: validation and application in metabolic, functional, and hemodynamic staging. Circulation 2003; 107:1991-1997.

- Olexa P, Olexova M, Gonsorcik J, et al. Uric acid a marker for systemic inflammatory response in patients with congestive heart failure? Wien Klin Wochenschr 2002; 28:211-215.

Author Info

Abhishek Das and SMKS Gurukul*

Department of General Medicine, Sree Balaji Medical College and Hospital Affiliated to Bharath Institute of Higher Education and Research, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, IndiaCitation: Abhishek Das, SMKS Gurukul, Study of Serum Uric Acid Levels in Acute Myocardial Infarction, J Res Med Dent Sci, 2021, 9 (5):252-257.

Received: 23-Apr-2021 Accepted: 21-May-2021