Research - (2022) Volume 10, Issue 8

Effective Management of Fake Drugs in Ghana, Nigeria, and Turkey

Senol Dane1*, Murat Akyuz2 and Michael Isaac Opusunju2

*Correspondence: Senol Dane, Department of Physiology, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, College of Health Sciences, Nile University of Nigeria, Abuja, Nigeria, Email:

Abstract

This study utilized a comprehensive review of the literature based on online databases to investigate the effective management of fake drugs in Nigeria, Ghana, and Turkey. The study conceptualized the menace of fake drugs and provided a common framework by which countries under study effectively manage the problem of fake drugs in their respective counties-measures undertaken to curb the counterfeit and substandard drug issues. The study concluded that, the trade in counterfeit and inferior pharmaceuticals jeopardizes not only the health system but all public institutions and that all the stakeholders involved, whether in Ghana, Nigeria, Turkey, or around the globe, must work together.

Keywords

Fake drugs, Counterfeit drugs, Substandard drugs, NAFDAC, Medicines

Introduction

Fake drugs are a global public health issue that kills, disables and injures both adults and children. No country is immune to this dilemma, which affects both emerging and developed economies. It is pertinent to note that counterfeiting drugs is not a new problem; in fact, it has been around for a long time. After all, one of the reasons the United Nations created the World Health Organisation (WHO) in 1948 is to coordinate health affairs such as monitoring and checkmating health- related matters, as well as drugs [1]. Nevertheless, fake drug production is a widespread and underreported issue, particularly in developing nations [2]. It has been averred that fake drug in developing counties have become a usual phenomenon where untoward industries produce drugs that endanger human life without carrying out proper laboratory test and experiment to ascertain whether the drugs produced is good enough for human consumption [3].

The WHO (2017), estimated that one-in-ten medical products circulating in low-income countries like Nigeria and Ghana and middle-income countries like Turkey are either substandard or falsified [4]. This suggests that people from these countries are taking medications that do not treat or prevent the intended diseases. Not only is this a waste of money for individuals and health systems that purchase these products, but inferior or fraudulent medical supplies can cause significant sickness or even death. In essence, a fake drug could be regarded as any medication which is produced and sold with the intent to deceptively represent its origin, authenticity, or effectiveness.

Whilst the WHO has been carrying out coordinated efforts for the abatement of counterfeit medications, scholars [5] has reported that up to about 15% of all drugs sold globally are fake, and in parts of Africa and Asia this figure exceeds 50%. As such, fake drugs management has become an issue of concern to the government and public since the majority of the populations of developing countries are affected by fake drugs. Fake drugs need proper control to ensure that only tested and experimented drugs that are approved and licensed by the various government agencies are allowed in any given country of the world. In Ghana, the agencies that manage fake drugs include Ghana’s Food and Drugs Authority (FDA), Pharmaceutical Society of Ghana and Ghana Pharmacy Council (GPC). In Nigeria, the agencies that manage fake drugs include the National Agency for Food and Drug Administration and Control (NAFDAC), Standard Organization of Nigeria (SON), Pharmacists Council of Nigeria (PCN), National Drug Law Enforcement Agency (NDLEA) amongst others. In Turkey, the agencies that manage fake drugs include the Ministry of Health, Advisory Commission for the Authorization of Medicinal Products for Human Use, Turkey’s Association of Research-Based Pharmaceutical Companies (AIFD) amongst others.

Over the years, the governments of low and middleincome countries like Ghana, Nigeria and Turkey have initiated agencies that are actively involved in managing and controlling fake drugs. However, it is still unclear whether the initiatives of these governments are effective. As such, further research is essential to better understand how these countries manage the menace of fake drugs.

The objective of this study is to investigate the effective management of fake drugs in Nigeria, Ghana, and Turkey by performing a comprehensive review of literature that investigated healthcare policies for tackling falsified drugs. The specific objectives are to determine the possible ways of managing fake drugs in Nigeria, Ghana and Turkey and explicate how fake drugs (substandard and counterfeit drugs) are being controlled. The scope of this study is restricted to the effective management of fake drugs in Nigeria, Ghana, and Turkey. The study covered fake drugs in terms of substandard drugs and counterfeit drugs.

Literature Review

Fake or counterfeit drugs

Drugs are used to cure or treat disease, relieve symptoms, alleviate pain, prevent disease or symptoms, eliminate, or reduce symptoms, and slow disease progression. On the other hand, the term “fake” refers to something that is not genuine but is presented as or appears to be genuine to make or produce something and claim it is genuine when it is not. Hence, one may conceptualise the meaning of fake drugs from the above-mentioned definitions.

Internationally, there is no approved description of fake or counterfeit drugs [6]. Substandard and fake or counterfeit drugs are classified differently in different countries and organizations. People have different perspectives or explanations for these drugs depending on the writer’s or speaker’s point of view. The working definitions that will be used in this research are as follows.

According to the WHO, counterfeit or fake drugs are intentionally and falsely mislabeled in terms of labeling and source [6]. Wright (2006), defined it as medicine with correct or incorrect ingredients and forged packaging [7]. The term “counterfeit drug” applies to both generic and branded products that are not genuine [8].

In addition, Newton et al. (2011), averred that a substandard drug is one that does not meet specifications [9]. A sub-standard drug is one that fails laboratory testing in terms of specification and classification. Unfortunately, some of these substandard drugs are being pushed onto the market in developing countries. According to Adepoju-Bello, et al. the identified types of substandard drugs include high and low ingredient concentrations, contamination, mislabeling difficulties with active ingredients, complications and inactive ingredients used as transporters for active ingredients in drugs, and poor protective material problems [10]. This demonstrates several methods for labeling a drug as substandard.

There is a long history of distinguishing between counterfeit and substandard drugs. The distinction between substandard and counterfeit drugs is critical, as is the distribution process. It is difficult to tell the difference between a counterfeit product and a substandard product. A genuine product may turn out to be substandard due to manufacturing flaws. A counterfeit drug, on the other hand, may meet the same standards as an authentic product and cannot be labeled as a substandard drug. Nevertheless, for the sake of conceptualization, a fake drug is one that is not genuine or counterfeit.

Management of fake drugs

It is difficult enough to detect errors in the entire process of manufacturing and distributing one’s pharmaceutical products, however, drugs companies and governments organisations must also deal with the problem of counterfeit medications, which are ineffective at best and lethal at worst [11]. Legitimate drugs can be diverted, or fake drugs can be created in parallel with and invisible to drugs companies’ supply chain, with their own distribution networks purposefully designed to be complex to conceal them [12]. Looking at the problem of management of fake drugs, it can be overwhelming and frightening for pharmaceutical professionals, as well as, for consumers who rely on companies and their government to provide them with safe and effective medications.According to the WHO (2017), one out of every ten medical products in low and middle-income countries like Ghana, Nigeria and Turkey amongst others is substandard or counterfeit. As such several of these countries have employed several means to ameliorate the issue.

In Ghana, the government launched a rigorous drug sampling and testing programme, with support from the US Pharmacopoeia and WHO, of which they published their findings regularly. They also took regulatory action against non-compliant importers or manufacturers, issuing fines and recalls in some cases. They were able to better prevent, detect, and respond to fake/substandard drugs on the Ghanaian market thanks to their strengthened and sustainable post-market surveillance programmes [13].

In Nigeria, through the use of agencies such as NAFDAC, SON, PCN, NDLEA amongst others, the government manages fake drugs by imposing strict drugs regulations. In terms of regulation, NAFDAC, which is the chief drug regulatory agency has taken a dual approach to regulate the drug distribution system, which it also sees as the root cause of Nigeria’s “fake drug problem.” First, since 2001, NAFDAC has attempted to “enlighten” Nigerians about the dangers of using low-quality, unregistered drugs, particularly through the media. Second, in conjunction with the NDLEA, NAFDAC set of task forces to checkmate drug retailers. These efforts had some indirect success in raising consumer awareness in Nigeria [14]. Anecdotal evidence gathered during fieldwork in Lagos and Ibadan between 2005 and 2007 revealed that many more Nigerians were aware of NAFDAC’s drug-related work rather than its sister agency dealing with illegal drugs [14]. Drug users, at least in urban areas, appeared to be aware of NAFDAC’s message that only registered drugs were safe to consume. Furthermore, these information campaigns, as well as changes in consumer behaviour, have resulted in much stronger self-regulation among Nigerian drug sellers.

In Turkey, whilst the government has the regulatory agencies and departments under her Ministry of health, periodically carry out raids to fish out counterfeit or fake drugs. In 2013, the authorities in Turkey carried out a series of raids across the country that took down a counterfeit medicines ring—they conducted 130 raids in nine provinces, uncovering a network making and distributing fake cancer drugs, including products that found their way onto the US market [15]. Since then, Turkey has implemented and strengthened its national programme of medicine serialization via 2D barcodes (the drug tracking system), which should make it difficult to carry out the illegal activity of drug faking.

Methodology

The study utilized a comprehensive review of the literature based on online databases such as PubMed, Medicines, and Healthcare-products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), Google Scholar, Scopus amongst others. Keywords “counterfeit drugs,” “counterfeit medicines,” “fake drugs,” “fake medicines” and “substandard and falsified medicines” were used to narrow down the search. The searches were run with terms associated with “low- and middle-income countries,” “Ghana,” “Nigeria” and “Turkey.” Additional articles were incorporated through systematic searches of the WHO websites and references of included articles and pertinent literature reviews.

Framework for fake drugs management agencies in Ghana, Nigeria, and Turkey

The nature of the pharmaceutical market, the wellrepresented interests of some economic actors and the limited capacity of state agencies have shaped regulatory policy in Ghana, Nigeria, and Turkey. The regulatory limits appear to be largely consistent with what has been written about the failures of drug regulation in developing countries, though there are some notable successes [16].

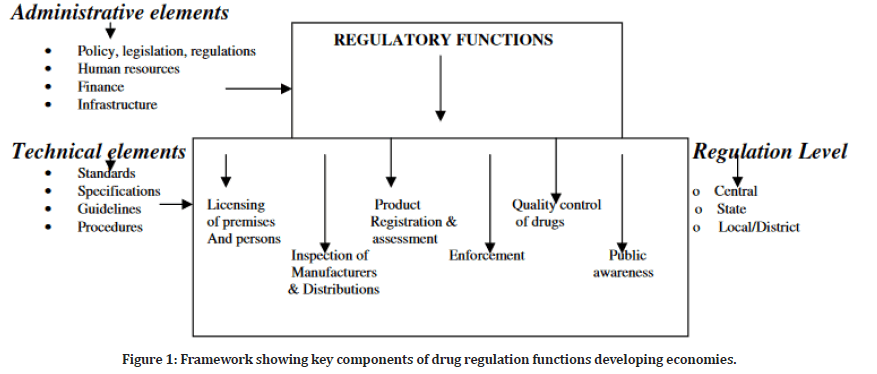

The functions in medicine regulation are reflected in the framework depicted in Figure 1. Administrative elements perform regulatory functions such as licensing of premises, persons, and practices, an inspection of manufacturers and distributors, product registration and assessment, enforcement, drug quality control, and public awareness. Drug regulation will fail if adequate policy, human resources, finances, and infrastructure are not in place. The technical elements constitute the major requirements that must be followed to meet the specified requirements. Every activity in a country’s regulatory functions is expected to function at all levels for effective management of the fake drugs problem.

Figure 1: Framework showing key components of drug regulation functions developing economies.

Licensing of premises and persons

Before granting a license to a person or a drug premises, the qualification of the person, the adequacy of the premises, as well as the quality of available equipment and processes is of the utmost importance. Licensing is a fundamental tool that developing countries use in certain conditions to ensure that people have access to the right medicines.

In Ghana, the Ghana Pharmacy Council (GPC) is a statutory regulatory body established by an Act of Parliament, charged with regulation and control of drugs in Ghana. The only people who are given license to manufacture, import, distribute or dispense are drug practitioners (pharmacists) registered with their relevant Councils having registered premises. Medical practitioners and nurses are not allowed to dispense drugs unless they possess a dispensing license to be Licensed Chemical Sellers (LCS) [17]. In Nigeria, the Pharmacists Council of Nigeria (PCN) is a statutory regulatory body established with regulation and control of drugs in Nigeria as well— with pharmacists given exclusive rights to dispense drugs and poisons [18]. Whereas in Turkey, the main regulatory authority is the Ministry of Health (MoH). Specifically, the Pharmaceutical Product and Medical Device Institution, an independent institution of the Turkish Ministry of Health, oversees the pharmaceutical sector. The Institution oversees all aspects of pharmaceutical regulation, including marketing authorization, manufacturing, pricing, import/export, and clinical trials (Table 1) [19].

| Licensing | Ghana, et al. [17] | Nigeria, et al. [18] | Turkey, et al. [19] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturing | Pharmacists by GPC | Pharmacists by PCN | Qualified persons by Turkish MoH |

| Importation | Should be under the care of a registered pharmacist | Should be under the care of a registered pharmacist | Pharmacists |

| Wholesale distribution | ” | ” | Qualified persons by Turkish MoH |

| Retail Pharmacy | ” | ” | Licensed premises Under the care of a registered pharmacist |

| Hospital pharmacy | Pharmacist | Pharmacist | ” |

| Other drug outlets | Varies from unlicensed premises to licensed vendor | Varies from unlicensed premises to licensed vendor | No available data |

Table 1: Ghana-Nigeria-Turkey licensing of premises and persons.

Inspection of manufacturers and distributions

Drug inspection is an important tool for monitoring fake or counterfeit drugs in developing economies to see if they are meeting the required standards. This is accomplished through physical visits to drug facilities by inspectors and the use of quality assurance laboratories. To avoid deception, a well-qualified inspector with good knowledge of pharmacy who is adequately trained and has the necessary legal authority is be used.

In Ghana and Nigeria, the different states of the countries make their own inspection of drug distribution and purchasing arrangements, which they do to ensure safety and cost-effectiveness [17,18]. In Turkey, on the other hand, the Ministry of Health has the responsibility for drug inspection of manufacturers, which they assess with the provision of their manufacturing authorization for compliance. They also have Good Distribution Practice (GDP) inspectors charged with the assessment of the drug wholesalers [19].

Product registration and assessment

This is where medications that fulfill minimum standards of efficacy, safety, and quality are granted marketing authorization/certificates and product licensing. A robust legal foundation, adequate and qualified people, adequate resources, a data retrieval system, and a system devoid of conflict of interest but with good accountability and openness are all required for the registration process to be effective. The validity of certificates issued in Ghana, Nigeria and Turkey is 5 years following the WHO guideline for registration and assessment (Table 2) [20].

| Registration & Assessment | Ghana | Nigeria | Turkey |

|---|---|---|---|

| Issuance of certificate & validity period | Ghana MoH 5 years’ license validity for imported products. | NAFDAC 5 years’ license validity for imported products. 2 years for local products | Turkish MoH 5 years license |

| SOP for staff | Complies with WHO standard | Complies with WHO standard | Available & can make independent assessments on drug safety |

| Post-marketing checks | Adequate Complies with WHO standard | ,, | ” |

| Drug sell, supply & price | Monitored by committee members from Ghana MoH | not under NAFDAC jurisdiction but under PCN | Monitored |

| External expert support | Available Using reputable regulating bodies of other countries | None | Available |

Table 2: Ghana-Nigeria-Turkey drug product registration and assessment.

Enforcement

Any drug regulating authority’s enforcement operates as the intelligence group that analyses cases, brings criminal prosecutions, works with information provided by individuals and consumers, and conducts raids and surveillance activities in suspected fake drug company places.

In Ghana, they have a Narcotics Unit as a division of the Ghana Police Service’s Criminal Investigations Department. As a result, the Narcotics unit's personnel are primarily mainstream detectives who receive additional training in crime detection at the Ghana Police Service’s Detective Training School. This gives them the ability to handle all types of criminal cases including fake drugs [21]. In Nigeria, the NDLEA in tandem with the NAFDAC is in charge of drug enforcement, which involves enforcing laws against the cultivation, processing, sale, trafficking and use of hard drugs, as well as fake drugs [21]. In Turkey, the Ministry of Health has an enforcement and intelligence unit in charge of implementing drug laws, which employs appropriately qualified intelligence agents.

These officers cooperate closely with Turkish police forces, the MHRA, the WHO Anti-Counterfeiting Taskforce, and several regulatory authorities around Europe. With this close coordination, information on the proliferation of fake drugs is easily reported and analysed [15].

Other strategies used to combat fake drugs include adequate communication with the public and healthcare professionals through the provision of a 24-hour anticounterfeiting hotline and the provision of a counterfeit medicine’s guideline for both pharmacists and the public, which educates them on how to avoid and report fake drug cases. While Nigeria has an enforcement agency, countries such as Ghana and Turkey work with their national Police to carry out task force actions.

Quality control of drugs

Before a marketing authorization/certificate is issued, the drug products are sent to a quality assurance laboratory for analysis to assure the quality of the drug products before they are sold on the market. The importance and adequacy of the laboratory system, equipment, materials, infrastructure, and workforce are considered a priority in every drug-regulating agency in developing countries for the effectiveness of regulation. This is because if a suspected drug product is confiscated, the laboratory will be used to determine the quality of the product, as well as the type of sentence that will be imposed on the violator. Most laboratory infrastructures and equipment are in Ghana and Turkey except for Nigeria. In addition, NAFDAC contracts some of the products to other laboratory institutions for analysis because the laboratories are inadequate to carry the volume of samples received and inadequate workforce.

Public awareness

Public enlightenment campaigns are a successful approach for improving consumer awareness and countering regulated product fake through print and electronic media, jingles, alert notifications, billboards, advertising in journals, publications, workshops, and seminars with stakeholders, and so on.

These efforts are aimed at educating the public on consumers’ rights to make informed choices, and they can empower the public to recognize and reject counterfeit items through increased public awareness. This strategy is well employed in Nigeria by the NAFDAC [14]. Regulating medication information helps to prevent false and misleading information from reaching the public and provides consumers and health care providers with better knowledge.

In Ghana, the LCS is an essential group for health care delivery because many people rely on them as their initial point of contact for drug demand and supply. Even though some of these merchants are licensed, they pose a risk to public health by offering consumers inaccurate, outdated, or counterfeit medications. The Ghana Social Marketing Foundation (GSMF) designed the care shop franchising concept to facilitate the training of franchisees that sign agreements and rebuild their stores in accordance with franchise requirements. The idea is that such stores where demand is great can be easily monitored, and they will also represent trust, better services, and a reliable supply chain to individuals who patronize them. The GSMF oversees medicine sourcing, distribution, monitoring, and evaluating franchises, as well as increasing the loyalty and trust of these drug vendors.

In Turkey, consumer organisations monitor and give recommendations to the MoH. They also raise queries about any topics that consumers require clarity on. The Turkish MoH provides a good communication network to the public and healthcare professionals by offering a 24-hour anti-counterfeiting (track and trace) online management system for both pharmacists and the public, the guideline educating people on how to avoid and report fake medication incidents [22].

Drug information to the general public is often disseminated via the governments’ bulletins and gazettes, as well as collaboration with stakeholders who impact public awareness. All the countries under study have legislative laws that guide them in the pursuit of public enlightenment.

Conclusion

This study has provided some information regarding the influx of counterfeit and substandard drugs into Ghana, Nigeria, and Turkey by conceptualizing the menace. It also provided a common framework by which countries under study effectively manages the problem of fake drugs in their respective counties-measures undertaken to curb the counterfeit and substandard drug issues.

In a broader sense, the trade in counterfeit and inferior pharmaceuticals jeopardises not only the health system but all public institutions. Corruption in the healthcare system may lead patients to believe that the drug supply is substandard. Solving the counterfeit drug problem is critical to ensuring that patients do not lose faith in the benefits of pharmaceuticals and stop taking their medications. The growth of the Internet, as well as the difficulty in policing drug vendors via the Internet, has resulted in a significant increase in consumer purchases of counterfeit pharmaceuticals. Controlling the supply of counterfeit drugs is difficult, but it is vital given the significant public health risks associated with counterfeit drugs, which can hurt or kill people. All the stakeholders involved, whether in Ghana, Nigeria, Turkey or around the globe, must work together if they are to curb the menace of fake drugs.

References

- https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/255355

- Cockburn R, Newton PN, Agyarko EK,et al. The global threat of counterfeit drugs: Why industry and governments must communicate the dangers. PLoS Med 2007; 4:e289.

- Blackstone EA, Fuhr JP, Pociask S. The health and economic effects of counterfeit drugs. Am Health Drug Benefits 2014; 7:216-224.

- https://www.who.int/news/item/28-11-2017-1-in-10-medical-products-in-developing-countries-is-substandard-or-falsified

- Aminu N, Sha'aban A, Abubakar A, et al. Unveiling the peril of substandard and falsified medicines to public health and safety in Africa: Need for all-out war to end the menace. Med Access 2017; 1.

- Almuzaini T, Choonara I, Sammons H. Substandard and counterfeit medicines: A systematic review of the literature. Br Med J 2013; 3:1-2.

- Wright E. Counterfeit drugs: Definitions; origins and legislation. Informa UK Ltd 2006.

- Bansal D, Malla S, Gudala K, et al. Anti-counterfeit technologies: A pharmaceutical industry perspective. Sci Pharm 2013; 81:1-4.

- Newton PN, Amin AA, Bird C, et al. The primacy of public health considerations in defining poor quality medicines. PLoS Med 2011; 8:1-5.

- Adepoju-Bello A. Quality assessment of ten brands of ofloxacin tablets marketed in Lagos, Nigeria. West African J Pharm 2017; 28:16-25.

- Zaman MH. Bitter pills: The global war on counterfeit drugs. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Phake RB. The deadly world of falsified and substandard medicines. Washington, DC: AEI Press. 2012.

- Danquah DA, Buabeng KO, Asante KP, et al. Malaria case detection using rapid diagnostic test at the community level in Ghana: Consumer perception and practitioners' experiences. Malar J 2016; 15:34.

- https://www.nafdac.gov.ng/

- https://www.securingindustry.com/pharmaceuticals/turkey-cracks-counterfeit-medicines-cabal/s40/a1921/

- Dukes J, Braithwaite J, Moloney JP. Pharmaceuticals, corporate crime and public health. cheltenham: Edward Elgar 2015.

- Afari-Asiedu S, Kinsman J, Boamah-Kaali E, et al. To sell or not to sell: The differences between regulatory and community demands regarding access to antibiotics in rural Ghana. J Pharm Policy Pract 2018; 11:30.

- from https://www.mondaq.com/nigeria/food-and-drugs-law/597042/legal-framework-for-carrying-on-pharmaceutical-business-in-nigeria

- https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/0-617-2716?contextData=(sc.Default)

- Ndomondo-Sigonda M, Miot J, Naidoo S, et al. Medicines regulation in Africa: Current state and opportunities. Pharm Med 2017; 31:383-397.

- https://au.int/en/newsevents/20190729/third-session-specialised-technical-committee-health-population-and-drug-control#:~:text=(2)%20years.-,The%203rd%20Ordinary%20Session%20of%20the%20Specialized%20Technical%20Committee%20on,Security%20for%20All%20African%20Citizens%2D https://www.drugtrackandtrace.co

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Author Info

Senol Dane1*, Murat Akyuz2 and Michael Isaac Opusunju2

1Department of Physiology, Faculty of Basic Medical Sciences, College of Health Sciences, Nile University of Nigeria, Abuja, Nigeria2Department of Business Administration, Nile University of Nigeria, Abuja, Nigeria

Received: 08-Jul-2022, Manuscript No. jrmds-22-68918; , Pre QC No. jrmds-22-68918(PQ); Editor assigned: 11-Jul-2022, Pre QC No. jrmds-22-68918(PQ); Reviewed: 25-Jul-2022, QC No. jrmds-22-68918; Revised: 30-Jul-2022, Manuscript No. jrmds-22-68918(R); Published: 06-Aug-2022