Research - (2022) Volume 10, Issue 2

Retrospective Analysis on Class 3 Mesial or Distal aspect of Mandibular Anterior Teeth Restored with Composite

Yuvashree CS and Delphine Priscilla Antony S*

*Correspondence: Delphine Priscilla Antony S, Department of Conservative dentistry and Endodontics, Saveetha Institute of Medical And Technical Sciences Saveetha University, India, Email:

Abstract

Introduction: Caries is the most common cause of oral pain and tooth loss, and it can be treated with amalgam, composite, porcelain, and gold restorations, as well as endodontic treatments and extraction. Because it can take hues that are more close to enamel, composite restorations have gained in popularity during the previous half-century. Aim: The aim of the study was to assess and analyse the mesial or distal aspect of Mandibular anterior teeth restored with composite. Materials and methods: This was a descriptive study, where all the patients’ data was collected by reviewing patients records and analysing the data of 86000 patients reported from June 2019 to February 2021 to the Department of conservative dentistry and endodontics, Private Dental college and hospitals, Chennai. Data was collected and tabulated, statistical analysis was done by SPSS–IBM. Results: From the statistical analysis it was found that nearly 29.23% of the patients who underwent Mandibular anterior teeth restoration was found to be most commonly seen in the age groups between 40-49 years with female predilection (79.38%). Class 3 LCR mesial (52%) was found to be more prevalent than distal (48%). The most commonly associated tooth was lower canines (21%). Conclusion: In this study, we observed that there is a significant difference between the age , gender and tooth number of patients who underwent class 3 composite restoration in the mesial or distal aspect of mandibular anterior teeth.

Keywords

Composite, Restoration, Class 3 LCR, Tooth number, Age, Gender

Introduction

Dental caries can be treated with amalgam, composite, and gold restorations, as well as endodontic therapy, excision of decaying dental tissues, and extraction [1,2]. Composite is of particular relevance in the restoration of caries since this relatively new technology (developed in the 1930s) allows for a wider spectrum of shades that are more similar to enamel, allowing the repair to appear invisible due to proper shade matching [3]. In comparison to most other restorative materials, it has a high compressive strength [4]. It also has tensile strength that is increased when heat is applied [5]. Furthermore, minor adjustments in the composite characteristics might open up a larger range of applications [6].

Because of its poor aesthetic features and suggested disputed biocompatibility, dental restorative composites have been developed in recent decades to replace amalgam [7]. Composite restorations, on the other hand, have demonstrated excellent overall clinical efficacy in small and medium-sized posterior cavities, with annual failure rates ranging from 1% to 3% [8].The size of posterior composite restorations has a substantial correlation with their survival [9]. Annual failure rates increased from 0.95 percent for single-surface restorations to 9.43 percent for four or more surface restorations, according to Bernardo et al. [10]. Large restorations have been demonstrated to be more susceptible to fracture-related failures, resulting in shorter lifespans [11]. The low fracture toughness of the composite material itself, as well as patient characteristics like bruxism, contributes to the increased vulnerability of big composite restorations to fracture [12]. In contrast to 1995–2005, Alvanforoush et al. found that the range of reported overall success rates for long-term clinical studies improved from 2006 to 2016 (minimum 64 percent to maximum 96.9%) (Minimum 50 percent to maximum 83 percent) [13].

However, the causes of failure have switched from high rates of secondary caries and wear to restoration fractures, tooth fractures, and endodontic therapy playing an increasingly important role [14]. The literature shows that modern particle filled composites still have limits when employed in big restorations due to their lack of hardness [15]. Because of these kinds of failures, it's still debatable whether direct restorative Composites should be employed in big, high-stress bearing applications like core build-ups or posterior crown restorations [16].

Our team has extensive knowledge and research experience that has translate into high quality publications [17-36]. Thus the aim of the study was to assess and analyse the mesial or distal aspect of Mandibular anterior teeth restored with composite.

Materials and Methods

The current study is a comparative and descriptive study which is performed in a university setting where all the patient data from June 2019 to February 2021 was collected, reviewed and analysed. The ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Committee (ethical approval number: SDC/SIHEC/2020/DIASDATA/ 0619-0320). The data of patients who underwent composite restorations in Mandibular anterior teeth was collected, cross verified with photographs and were compiled for statistical analysis on SPSS Software. The sampling bias is minimised by incorporating random sampling methods. There was high internal validity and low external validity in our study.

Inclusion criteria

• Patients who had class 3 dental caries.

• Patients who underwent class 3 composite restoration for the same.

• Patients of all age groups.

Exclusion criteria

• Composite restorations other than class 3 cavity.

• Improper & incomplete data.

SPSS (statistical package for social studies) version 22.0 (IBM corporation) was used for data entry and descriptive statistics. The Chi-squared test used to compare groups (P< 0.05) was considered significant.

Results

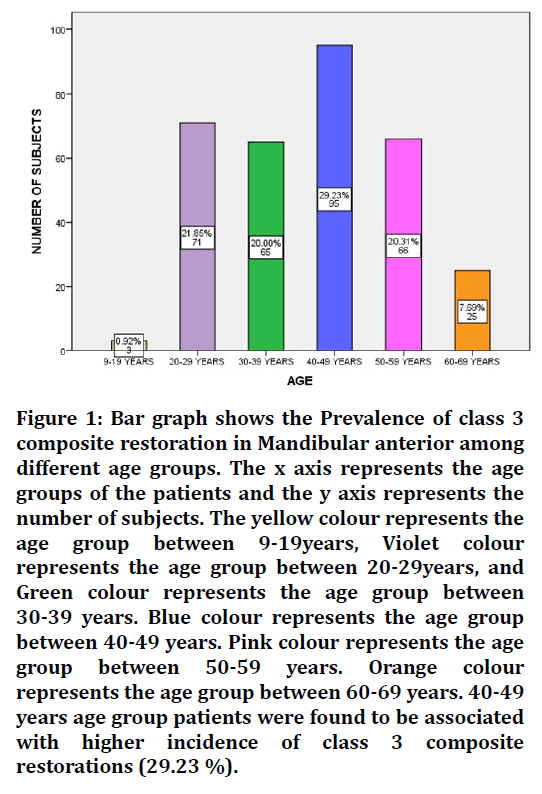

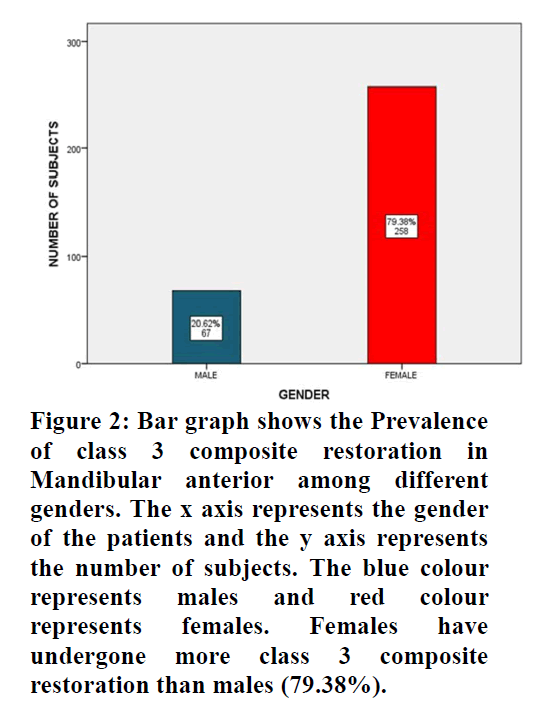

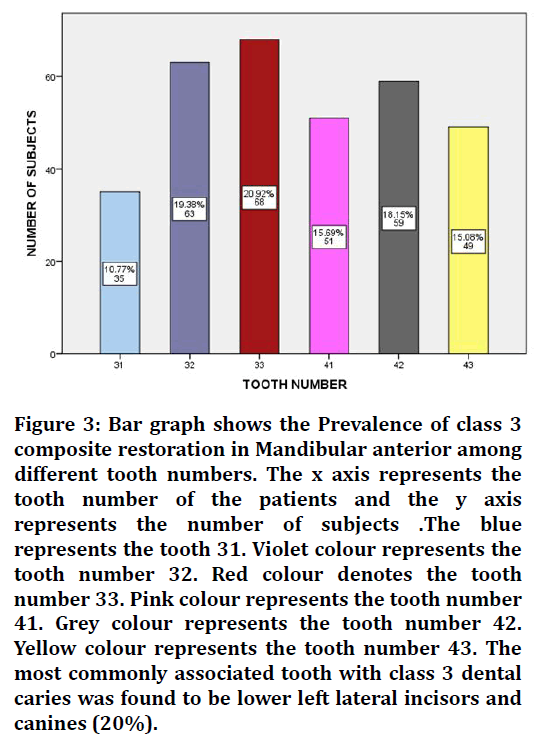

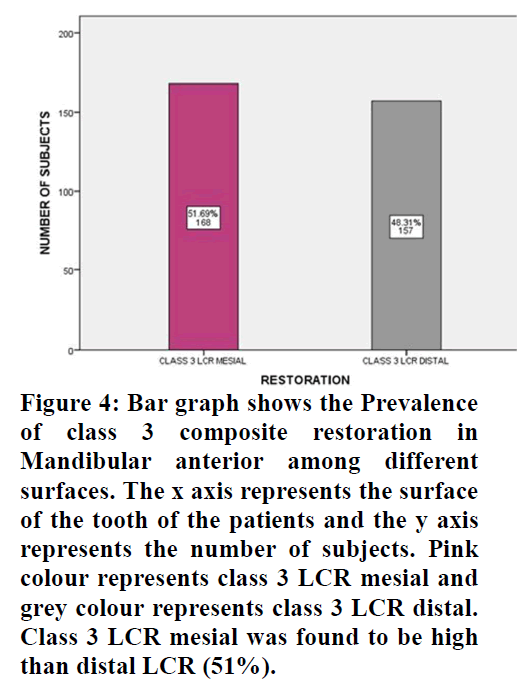

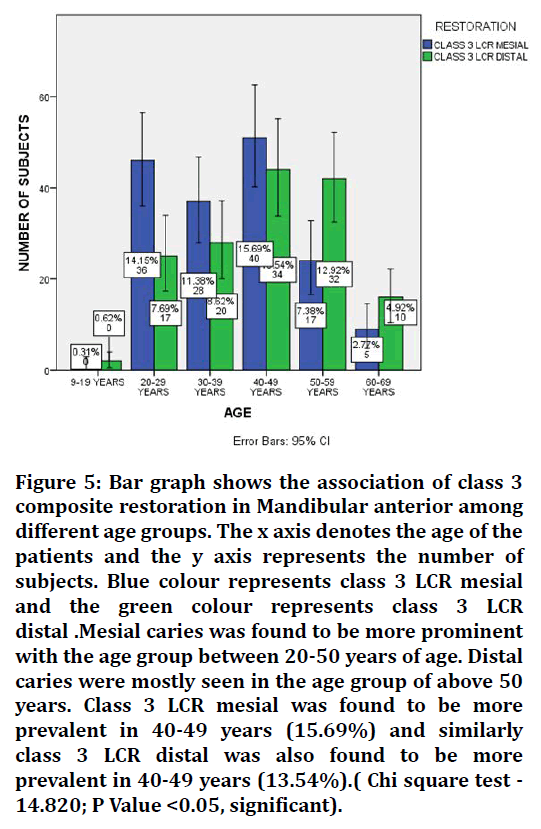

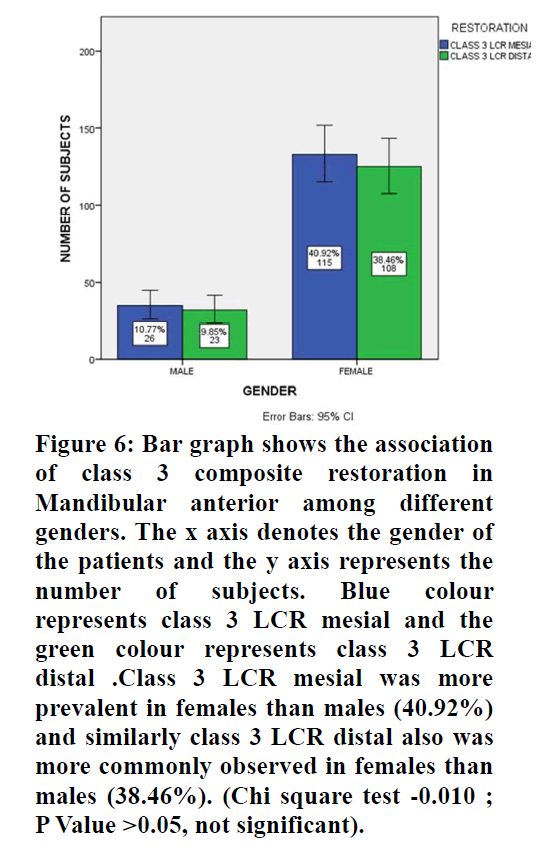

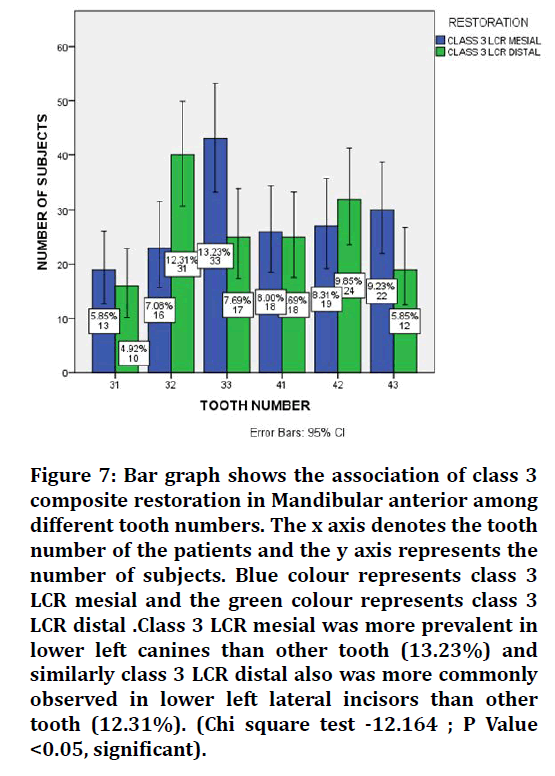

From the statistical analysis it was found that nearly 29.23% of the patients who underwent Mandibular anterior teeth restoration were found to be most commonly seen in the age groups between 40-49 years with female predilection (79.38%) (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Class 3 LCR mesial (52%) was found to be more prevalent than distal (48%) (Figure 3). The most commonly associated tooth was lower left lateral incisors and lower canines (21%) (Figure 4). Figure 5 shows the association of class 3 composite restoration in Mandibular anterior among different age groups. Mesial caries was found to be more prominent with the age group between 20-50 years of age. Distal caries were mostly seen in the age group of above 50 years. Class 3 LCR mesial was found to be more prevalent in 40-49 years (15.69%) and similarly class 3 LCR distal was also found to be more prevalent in 40-49 years (13.54%). Figure 6 shows the association of class 3 composite restoration in Mandibular anterior among different genders. Class 3 LCR mesial was more prevalent in females than males (40.92%) and similarly class 3 LCR distal also was more commonly observed in females than males (38.46%). Figure 7 shows the association of class 3 composite restoration in Mandibular anterior among different tooth numbers .Class 3 LCR mesial was more prevalent in lower left canines than other tooth (13.23%) and similarly class 3 LCR distal also was more commonly observed in lower left lateral incisors than other tooth (12.31%).

Figure 1. Bar graph shows the Prevalence of class 3 composite restoration in Mandibular anterior among different age groups. The x axis represents the age groups of the patients and the y axis represents the number of subjects. The yellow colour represents the age group between 9-19years, Violet colour represents the age group between 20-29years, and Green colour represents the age group between 30-39 years. Blue colour represents the age group between 40-49 years. Pink colour represents the age group between 50-59 years. Orange colour represents the age group between 60-69 years. 40-49 years age group patients were found to be associated with higher incidence of class 3 composite restorations (29.23 %).

Figure 2. Bar graph shows the Prevalence of class 3 composite restoration in Mandibular anterior among different genders. The x axis represents the gender of the patients and the y axis represents the number of subjects. The blue colour represents males and red colour represents females. Females have undergone more class 3 composite restoration than males (79.38%).

Figure 3. Bar graph shows the Prevalence of class 3 composite restoration in Mandibular anterior among different tooth numbers. The x axis represents the tooth number of the patients and the y axis represents the number of subjects .The blue represents the tooth 31. Violet colour represents the tooth number 32. Red colour denotes the tooth number 33. Pink colour represents the tooth number 41. Grey colour represents the tooth number 42. Yellow colour represents the tooth number 43. The most commonly associated tooth with class 3 dental caries was found to be lower left lateral incisors and canines (20%).

Figure 4. Bar graph shows the Prevalence of class 3 composite restoration in Mandibular anterior among different surfaces. The x axis represents the surface of the tooth of the patients and the y axis represents the number of subjects. Pink colour represents class 3 LCR mesial and grey colour represents class 3 LCR distal. Class 3 LCR mesial was found to be high than distal LCR (51%).

Figure 5. Bar graph shows the association of class 3 composite restoration in Mandibular anterior among different age groups. The x axis denotes the age of the patients and the y axis represents the number of subjects. Blue colour represents class 3 LCR mesial and the green colour represents class 3 LCR distal .Mesial caries was found to be more prominent with the age group between 20-50 years of age. Distal caries were mostly seen in the age group of above 50 years. Class 3 LCR mesial was found to be more prevalent in 40-49 years (15.69%) and similarly class 3 LCR distal was also found to be more prevalent in 40-49 years (13.54%).( Chi square test - 14.820; P Value <0.05, significant).

Figure 6. Bar graph shows the association of class 3 composite restoration in Mandibular anterior among different genders. The x axis denotes the gender of the patients and the y axis represents the number of subjects. Blue colour represents class 3 LCR mesial and the green colour represents class 3 LCR distal .Class 3 LCR mesial was more prevalent in females than males (40.92%) and similarly class 3 LCR distal also was more commonly observed in females than males (38.46%). (Chi square test -0.010 ; P Value >0.05, not significant).

Figure 7. Bar graph shows the association of class 3 composite restoration in Mandibular anterior among different tooth numbers. The x axis denotes the tooth number of the patients and the y axis represents the number of subjects. Blue colour represents class 3 LCR mesial and the green colour represents class 3 LCR distal .Class 3 LCR mesial was more prevalent in lower left canines than other tooth (13.23%) and similarly class 3 LCR distal also was more commonly observed in lower left lateral incisors than other tooth (12.31%). (Chi square test -12.164 ; P Value <0.05, significant).

Discussion

The esthetic restoration of anterior teeth can be quite challenging not only because of the available material and technique, but also from the patients and parents point of view.

In the current study Figure 1 showed that class 3 composite restoration in mandibular anterior teeth among different age groups is more prevalent in 40-49years of age (29.23%) and it is less prevalent among the age groups below 20 [37]. The study conducted by Lubisich EB etal, 2011 revealed that older patients are more prevalent than young patients [38]. Lubisich reported that patients of 50 years of age were found to have more class 3 dental caries and restored with composite when compared to individuals among 20 years of age which showed similar results in relation to our study [38,39]. Similarly, the effect of age on restoration longevity has been identified in other studies involving restorations in different locations on teeth, but the reason for this has not been established. It may simply be related to the size of the lesions, since it was established that increasing cavity size was associated with a shorter time to failure and also that there was a positive correlation between increasing patient age and increasing cavity size, longevity and discoloration.

From Figure 2, this study shows female predilection. The finding that more carious teeth were observed in female subjects in both primary and permanent dentition than in male subjects is in agreement with the findings of other studies. This gender-wise difference was highly significant (P<0.01). Mansbridge reviewed several studies presenting data about the gender predisposition of caries and revealed that most of the researchers attribute it to the early eruption of teeth in females than in the males. These early erupted teeth, exposed to risk factors for initiation and progression of dental caries, are responsible for the occurrence of dental caries. Hence, it is logical to assume that the female subject's teeth would decay more than the teeth of the male subjects of the same age. Bhardwaj et al. [38,39] revealed contrasting results, showing male patients with higher prevalence of dental caries than among females. The study conducted by Rahel Addis reported contrasting results that males were 2 times more likely to have dental caries than female. Similar to the current study, in Iran females were 1.4 times more likely to have dental caries [33]. This may be due to lower salivary flow rate, tooth eruption, and females acquiring their teeth earlier than males [34].

Figure 3 shows the most commonly associated tooth with composite restoration. Lower left Canines show more prevalence than other teeth. From figure 4, it is evident that class 3 LCR mesial aspect was found to be more prevalent than distal aspect According to Lubisich et al. the composite restorations in the mesial aspect of the tooth was found to be higher than the distal composite restoration [38]. The contrast results obtained from the study conducted by Mustafa et al , showed that more caries were observed on distal surfaces of central and lateral incisors and premolars than on other surfaces, except those of maxillary central and lateral incisors. The reason for this phenomenon could be a combination of complicated surface morphology and difficult access for effective oral hygiene.

By correlating the age, gender of patients who underwent class 3 composite restorations, it was found that more Class 3 composite restoration was most commonly associated between 40-49 years of age with female predilection (Figure 5 and Figure 6).

By correlating the tooth number of patients who underwent class 3 composite restoration, lower left canines shows more prevalence with respect to class 3 LCR mesial and class 3 LCR distal is most common in lower left lateral incisors. Macek et al. reported that the lower molars were the most severely affected teeth in the entire dentition. It was observed that molar teeth were more prone to caries than incisors, canines, or premolars in all the age-groups. This study revealed contrasting results to the current study.

The limitations of our study include a very small sample size and cannot be generalised to a larger population.

Conclusion

The success or failure of a resin composite restoration is determined by a number of factors. Although it is easy to point the finger at the producer and demand a better material, a better material utilised incorrectly will not result in a better repair. Before looking for that better content, it's vital to take a step back and assess how the material is being used to ensure that all of the fundamentals are addressed. Manufacturers can—and should—be held liable if a material on the market fails to function as advertised; nonetheless, most manufacturers strive to provide the best materials available to the profession. It is our job as dental practitioners to follow these guidelines.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to acknowledge the help and support rendered by the Department of Aesthetic dentistry, Saveetha Dental college and Hospitals, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha University for their constant assistance with the research.

Funding

The present project is funded by

• Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha Dental College and Hospitals, Saveetha University

• Jembu Printers Private Ltd., Chennai.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Pitts NB, Zero DT, Marsh PD, et al. Dental caries. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017; 3:1-6.

- https://books.google.co.in/books/about/Dental_Caries.html?id=gb4zEAAAQBAJ&redir_esc=y

- Sherwood IA. Essentials of operative dentistry. Boydell & Brewer Ltd 2010.

- González II. Posterior reinforced endodontic composite restoration. J Dent Oral Sci 2021; 3:1-4.

- Rahman MS, Faris TM. The efficacy of two different composite liners in preventing microleakage in deep class II glass- ceramic microhybrite composite restoration (in vitro study). J Sulaimani Med College 2014; 4:31–45.

- Nassar M, Al-Fakhri O, Shabbir N, et al. Teaching of the repair of defective composite restorations in middle eastern and north African dental schools. J Dent 2021; 103753.

- Committee ACCACR, AMS CACRC Commercial Aircraft Composite Repair Committee. Core restoration of thermosetting composite components. 2014.

- Dhoum S, Jabrane K, Dhaimy S, et al. Indirect posterior restoration: Composite inlays. Biomed J Sci Tech Res 2018; 5:4312-4316.

- Nicholson J, Czarnecka B. Composite resins. Materials Direct Restoration Teeth 2016; 37–67.

- Bernardo M, Luis H, Martin MD, et al. Survival and reasons for failure of amalgam versus composite posterior restorations placed in a randomized clinical trial. J Am Dent Assoc 2007; 138:775–783.

- Sugama T. Recycled waste-based cement composite patch materials for rapid/permanent road restoration. Brookhaven National Laboratory 2001.

- Nunes JP, Bernardo CA, Pouzada AS, et al. Formation and characterization of carbon/polycarbonate towpregs and composites. J Compos Materials 1997; 31:1758–77.

- Alvanforoush N, Palamara J, Wong RH, et al. Comparison between published clinical success of direct resin composite restorations in vital posterior teeth in 1995-2005 and 2006-2016 periods. Aust Dent J 2017; 62:132–45.

- Miletic V. Dental composite materials for direct restorations. Springer 2017; 319.

- http://www.quintpub.com/display_detail.php3?psku=B8236#.YgIP9dVBzIU

- Shen C, Ralph Rawls H, Esquivel-Upshaw JF. Phillips’ science of dental materials E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences 2021; 448.

- Muthukrishnan L. Imminent antimicrobial bioink deploying cellulose, alginate, EPS and synthetic polymers for 3D bioprinting of tissue constructs. Carbohydr Polym 2021; 260:117774.

- PradeepKumar AR, Shemesh H, Nivedhitha MS, et al. Diagnosis of vertical root fractures by cone-beam computed tomography in root-filled teeth with confirmation by direct visualization: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Endod 2021; 47:1198–214.

- Chakraborty T, Jamal RF, Battineni G, et al. A Review of prolonged post-COVID-19 symptoms and their implications on dental management. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18.

- Muthukrishnan L. Nanotechnology for cleaner leather production: A review. Environ Chem Lett 2021; 19:2527–2549.

- Teja KV, Ramesh S. Is a filled lateral canal-A sign of superiority? J Dent Sci 2020; 15:562–3.

- Narendran K, MS N, Sarvanan A. Synthesis, characterization, free radical scavenging and cytotoxic activities of phenylvilangin, a substituted dimer of Embelin. Indian J Pharm Sci 2020; 82:909-912.

- Reddy P, Krithikadatta J, Srinivasan V, et al. Dental caries profile and associated risk factors among adolescent school children in an Urban South-Indian City. Oral Health Prev Dent 2020; 18:379–386.

- Sawant K, Pawar AM, Banga KS, et al. Dentinal microcracks after root canal instrumentation using instruments manufactured with different NiTi alloys and the SAF System: A systematic review. Adv Sci Inst Ser E Appl Sci 2021; 11:4984.

- Bhavikatti SK, Karobari MI, Zainuddin SLA, et al. Investigating the antioxidant and cytocompatibility of Mimusops elengi Linn extract over human gingival fibroblast cells. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18.

- Karobari MI, Basheer SN, Sayed FR, et al. An In Vitro stereomicroscopic evaluation of bioactivity between neo MTA Plus, pro root mta, biodentine & glass ionomer cement using dye penetration method. Materials 2021; 14.

- Rohit Singh T, Ezhilarasan D. Ethanolic extract of lagerstroemia speciosa (L.) Pers., Induces apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in HepG2 Cells. Nutr Cancer 2020; 72:146–56.

- Ezhilarasan D. MicroRNA interplay between hepatic stellate cell quiescence and activation. Eur J Pharmacol 2020; 885:173507.

- Romera A, Peredpaya S, Shparyk Y, et al. Bevacizumab biosimilar BEVZ92 versus reference bevacizumab in combination with FOLFOX or FOLFIRI as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 3:845–55.

- Raj RK. β-Sitosterol-assisted silver nanoparticles activates Nrf2 and triggers mitochondrial apoptosis via oxidative stress in human hepatocellular cancer cell line. J Biomed Mater Res A 2020; 108:1899–908.

- Vijayashree Priyadharsini J. In silico validation of the non-antibiotic drugs acetaminophen and ibuprofen as antibacterial agents against red complex pathogens. J Periodontol 2019; 90:1441–1448.

- Priyadharsini JV, Girija AS, Paramasivam A. In silico analysis of virulence genes in an emerging dental pathogen A. baumannii and related species. Arch Oral Biol 2018; 94:93-98.

- Uma Maheswari TN, Nivedhitha MS, Ramani P. Expression profile of salivary micro RNA-21 and 31 in oral potentially malignant disorders. Braz Oral Res 2020; 34:e002.

- Gudipaneni RK, Alam MK, Patil SR, et al. Measurement of the maximum occlusal bite force and its relation to the caries spectrum of first permanent molars in early permanent dentition. J Clin Pediatr Dent 2020; 44:423–428.

- Chaturvedula BB, Muthukrishnan A, Bhuvaraghan A, et al. Dens invaginatus: A review and orthodontic implications. Br Dent J 2021; 230:345–350.

- Kanniah P, Radhamani J, Chelliah P, et al. Green synthesis of multifaceted silver nanoparticles using the flower extract of Aerva lanata and evaluation of its biological and environmental applications. Chem Select 2020; 5:2322–31.

- Maserejian NN, Hauser R, Tavares M, et al. Dental composites and amalgam and physical development in children. J Dent Res 2012; 91:1019–1025.

- Köhler B, Rasmusson CG, Ödman P. A five-year clinical evaluation of Class II composite resin restorations. J Dent 2000; 28:111-116.

- Lubisich EB, Hilton TJ, Ferracane JL, et al. Association between caries location and restorative material treatment provided. J Dent 2011; 39:302–308.

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Indexed at, Google scholar, Cross ref

Author Info

Yuvashree CS and Delphine Priscilla Antony S*

Department of Conservative dentistry and Endodontics, Saveetha Institute of Medical And Technical Sciences Saveetha University, Chennai, IndiaReceived: 26-Jan-2022, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-46859; , Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-46859 (PQ); ; Editor assigned: 28-Jan-2022, Pre QC No. JRMDS-22-46859 (PQ); ; Reviewed: 14-Feb-2022, QC No. JRMDS-22-46859; Revised: 18-Feb-2022, Manuscript No. JRMDS-22-46859 (R); Published: 25-Feb-2022